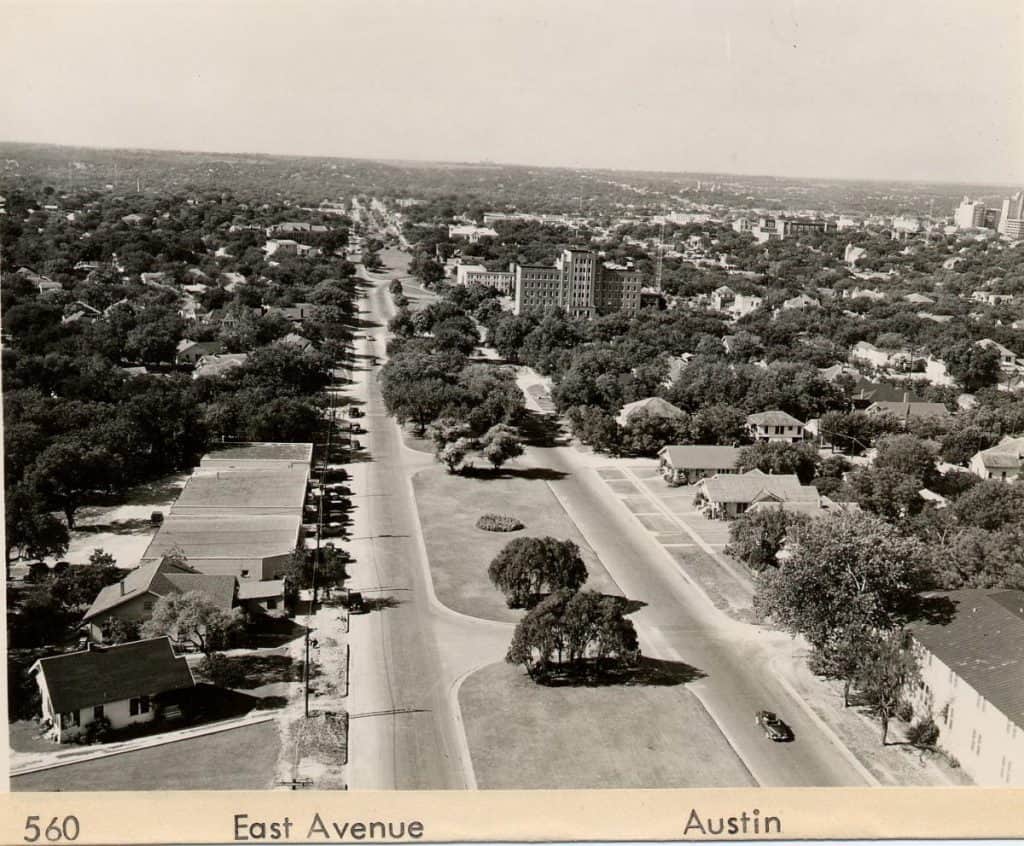

The St. John neighborhood of North Austin is a historically Black community that dates to 1894, when emancipated slaves bought 300 acres of land. The city’s largest public infrastructure investment here took place from the 1950s into the 1960s, when construction of Interstate 35 split the neighborhood in half. The city proposed its second largest public infrastructure investment in 2008, in the form of a police substation and municipal court.

“It was really an investment in punishment, and not an investment in housing, parks, jobs and childcare,” says Greg Casar, who intensively campaigned in the neighborhood before becoming its city council representative in 2015. Once in office, Councilmember Casar decided the police station plan had got to go, and worked with community members to come up with alternatives for the vacant 19-acre lot.

That years-long engagement has come to fruition. In July, Austin City Council voted to move forward with a developer on a mixed-use project that will triple the size of a small existing park, add retail and non-profit space, and build hundreds of affordable homes with Austin’s new Right to Stay and Right to Return policies, which allow working-class families currently living in the gentrifying neighborhood to find permanently affordable places to stay, and also allow displaced families with historic ties to the neighborhood to be preferred for affordable units.

“My hope is that this can really serve as a model of how we can develop dozens more acres of city-owned property, where we get the housing stock we need so that people can come back to neighborhoods they’ve been pushed out of,” says Casar.

The history of this lot — located right off Interstate 35 — is long and complex. It was an orphanage and elementary school before becoming a Home Depot and car dealership. The city purchased it in 2008 with funds approved in a 2006 bond election to build a police substation and municipal court. The plans stalled and opposition grew: Many residents didn’t want increased police presence, but they also felt the vacant, trash-strewn lot was a blight to the neighborhood.

“You could easily see the existing two options were not comfortable or acceptable for residents, because of the perception and reasoning of why they thought those two entities wanted to be in the neighborhood,” says Reverend Daryl Horton, of the local Mt. Zion Baptist Church.

Concerns around the lot kept surfacing as Casar campaigned through the neighborhood. After he became a city council member, his office conducted door-knocking efforts and digital outreach resulting in over 600 survey responses and several community input meetings on the future of the site. In 2017, Austin City Council authorized a formal community-based visioning process to come up with alternative plans.

One major challenge shaped the process: The city still owed about $10.8 million in bond debt from purchasing the property, an amount that needed to be paid back to move forward on new redevelopment. “If we put huge, revenue-generating uses on the property to pay off the bonds, you might have so much high-income housing, retail or office that it would be counterproductive,” Casar says. “So the community had to really work on making sure we could bring forward a project that the majority of housing was affordable … that it would bring parks, jobs and childcare to the community, and also cover that $10.8 million gap.”

Weighed down by negative news?

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.Casar worked with a core group of community leaders, including Reverend Horton and the St. John Regular Baptist Association, the group that purchased the 300 acres that founded the neighborhood. There was also Thelma Williams, the 80-year-old community activist known as “Grandma Wisdom” who grew up in St. John; Akeem McLennon, the St. John Neighborhood Association president; and Cherelle Vanbrakle, who grew up here — but could not afford to buy property to stay. She directs health promotion and community advocacy at the local People’s Community Clinic.

“It started with having conversations with community members,” Vanbrakle says. “Then there were lots of block walks, community meetings at the neighborhood center, and a charette where community members came in to talk about what they wanted.”

Many residents wanted a grocery store, according to Vanbrakle, “because you have to cross a highway to get to any grocery store in that corridor.” Affordable housing also ranked high — many longtime Black residents had been displaced (including Vanbrakle) or were struggling to stay as the area gentrified.

In 2018, Austin City Council adopted Right to Stay and Right to Return policies for families affected by gentrification in certain Austin neighborhoods. Those policies served as inspiration as community members envisioned affordable housing for this site.

In July 2020, the City Council approved the community vision and began a formal request for proposals process. The RFP was directly shaped by community input. “Nobody was even allowed to bid on the project unless the majority of the housing was affordable, unless they committed to Right to Stay and Right to Return policies, unless they expanded the nearby park and brought jobs and retail to the community,” Casar says. “Those were baseline requirements for even starting.”

“In Austin, for the African American community, there is a history of promises being made and not being fulfilled, and asking us what we want but the process moves forward as if our feedback was never given,” Reverend Horton notes. “I thought this was a huge gain for us … in that the RFP looked for people who could honor the recommendations of the community.”

For the winning proposal, private developer Greystar will partner with the Housing Authority of the City of Austin to build at least 560 housing units, half of which will be for households earning between 50 and 70 percent of Austin’s median family income. A park adjacent to the site will be expanded with a splash pad, playground, community garden and walking trails. There will be at least 15,000 square feet of retail and “support services space” responsive to community needs. Greystar will pay off the $10.8 million in bond debt.

While construction is expected to begin next year, the engagement isn’t done. “We’ll be working with [Greystar] to improve the plans,” Casar says. “I think we could have a lot less parking space and more housing, I think we can have a stronger mix of homeownership and rental options, I believe we can have units that are lower income.”

For Vanbrakle, this next phase is crucial. “We still have projects in Austin where the design and RFP were great, but that company has not been able to financially bring it to fruition,” she points out. “The accountability piece, because it’s no longer under the city, is less clear.”

Austin’s Right to Return policy is also untested. The program hasn’t been formally utilized by the city yet; Council Member Casar believes this will be one of the first developments to implement it. In Portland, Oregon, which implemented a Right to Return policy in 2014, the program has been slow going, without enough affordable rental housing to meet demand. While the city set a goal of helping 65 families buy homes, only nine purchased in the first four years of implementation.

Still, the partnership between Councilmember Casar and community leaders has ensured the St. John’s community has a seat at the table — and the council member hopes it can be replicated elsewhere. “It’s been several years to get to this point, but if we can show that this works … I hope that more and more communities can pick this up as a template.”

“The community piece is just so important.” As Vanbrakle puts it, “You have to let the community lead the work, because they have the solution.”

This story originally appeared in Next City.