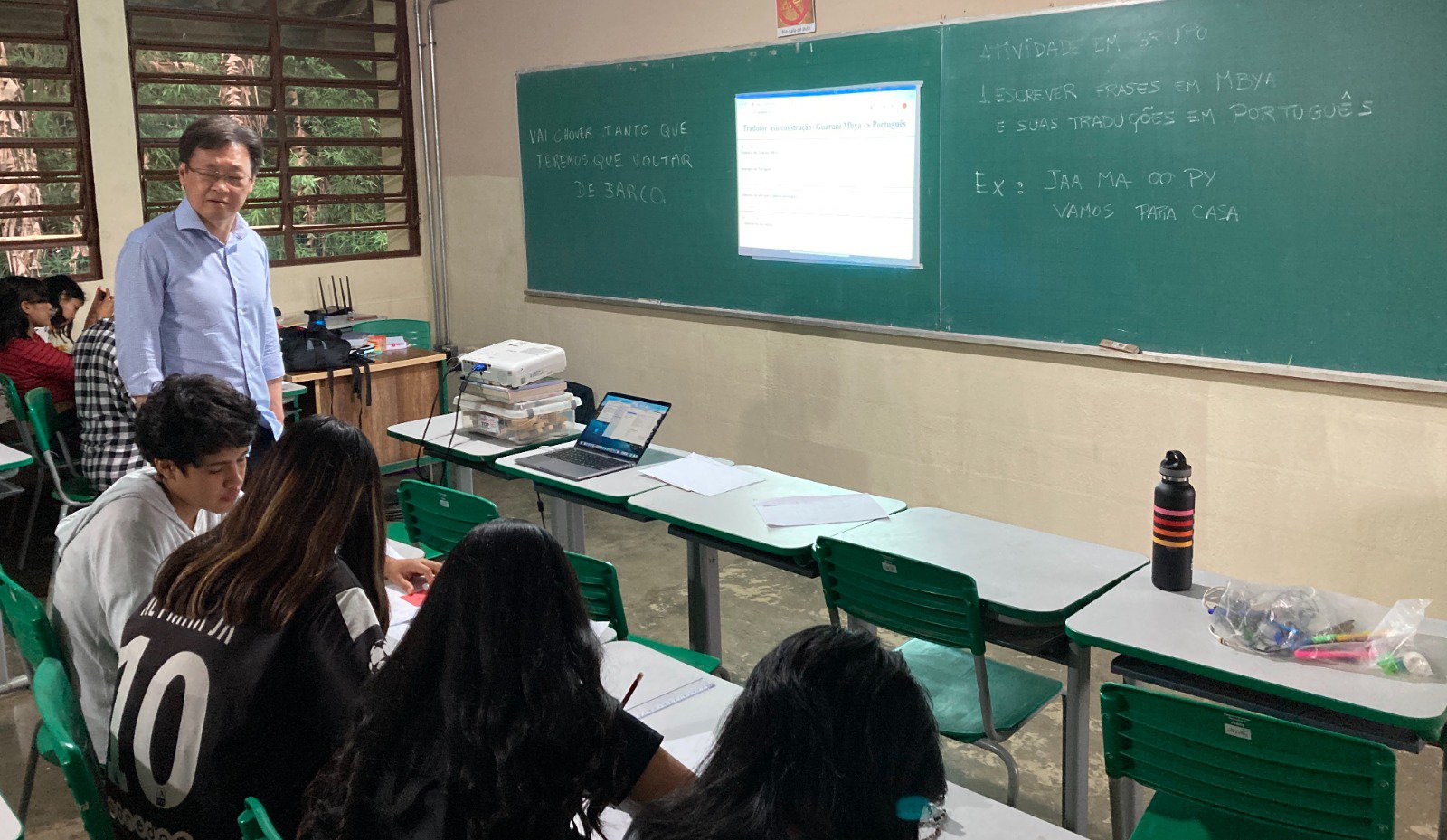

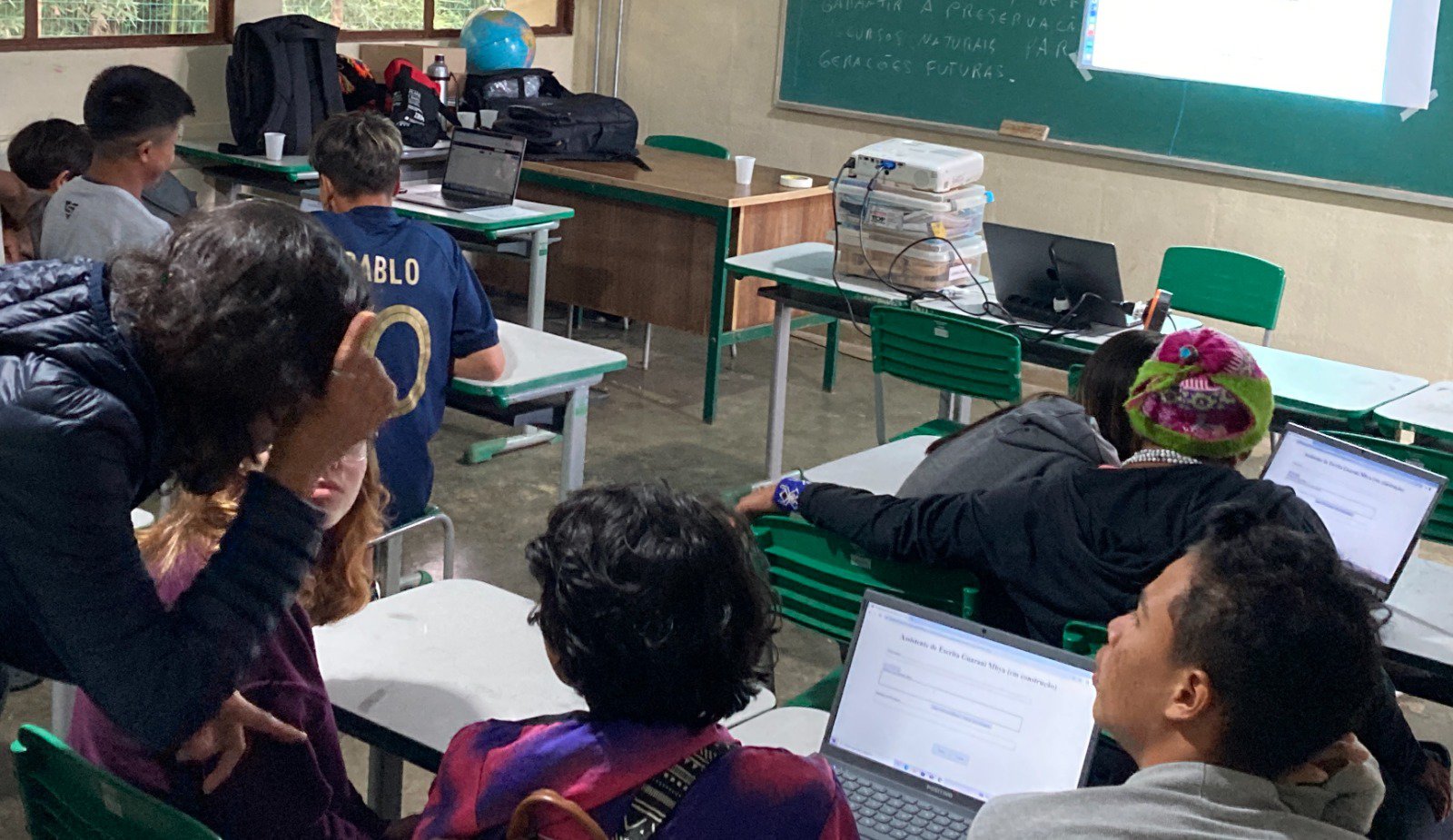

Huddled in small groups around laptops, 20 Brazilian teenagers — a group including TikTok influencers and gamers — are using an app to build a skill that’s vital to the future of their entire community.

The teenagers belong to the Guarani Indigenous people, based in a community two hours from São Paulo, and they are fluent in speaking both Portuguese and their mother tongue, Guarani Mbya. But when it comes to writing, they often default to Portuguese as that’s what they were first taught to write in, putting the Guarani Mbya language in its written form at risk of disappearing.

But since March of this year, they’ve been using an app to improve their ability to write in Guarani Mbya. The “Linguistic Assistant” app works like the autocorrect and text suggestion feature on cell phones to help them build on the sentences they start writing themselves.

The app is part of a project funded by IBM to create AI tools to help preserve and expand the use of Indigenous languages in Brazil. The students — who make up the sole high school class across seven villages of around 3,000 people, on a reservation of 23,000 square miles — were nominated by their wider community to be the focus of IBM’s AI for Indigenous languages social impact work in their region.

The results so far are promising, according to Dr. Claudio Pinhanez, an AI specialist at IBM and visiting professor at the University of São Paulo (USP), who is leading the project. “By the end of the semester, we saw they were starting to write longer sentences on their own in their language. The progress they were making is amazing,” he says.

Digital empowerment for vulnerable languages

Guarani Mbya is one of 202 Indigenous languages spoken in Brazil, with 190 of them considered at risk of dying out — and 22 already have. With around 17,000 speakers, Guarani Mbya is classified by UNESCO as a vulnerable language, meaning that while it’s widely spoken, its use is restricted to certain domains, for example, like the home, or with certain family members.

Of the 7,000 or so languages that exist in the world, about a fifth are thought to be endangered, with the United Nations estimating that half of these will be extinct or close to it by 2100 — the majority being Indigenous languages. Hence it’s declared 2022 to 2032 the International Decade of Indigenous Languages, to help increase resources, support and awareness for their protection, recognizing in particular the role technology has to play in what it calls “digital empowerment.”

Weighed down by negative news?

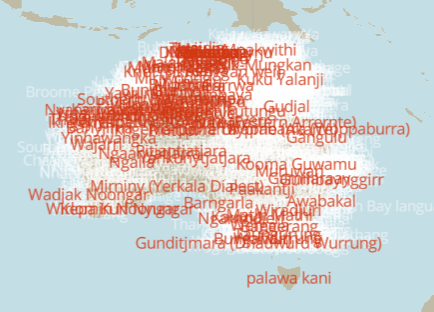

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.The movement to prevent Indigenous languages from disappearing has prompted a number of tech-centric language preservation and expansion projects like the one Dr. Pinhanez is leading at IBM and USP. For example, in Australia, where First Nations people speak more than 250 Indigenous languages, the University of Melbourne has launched its 50 Words project, an interactive language map that aims to offer at least 50 words of each Australian Indigenous language, as part of a nationwide Indigenous language preservation movement.

In neighboring New Zealand, nonprofit media organization Te Hiku has developed an app to collect oral recordings of Indigenous languages across the region, to help speakers boost their everyday use of their native language. And recognizing, as the Guarani people have, that the written form of a language can be challenging and equally important to preserve, a type foundry worked closely with Indigenous communities in Canada to develop new typefaces that make it easier for them to express themselves in writing.

Buoyed by how the Guarani teens have embraced technology to improve their written native language skills, Dr. Pinhanez and his team now plan to evolve the chatbot from a desktop app to one that can be downloaded to a cell phone, which will look and feel like WhatsApp.

“[The teens] see writing as a way to integrate their many communities, and to be able to tell their own stories in a way that is more stable than just speech. The community told us their youth were very interested in computers and engaged in social media, but needed to improve their native language writing, and that’s where they want us to help,” says Dr. Pinhanez.

He and his team are also keen to offer the tool as a free resource to other Indigenous communities, emphasizing that this is a strictly nonprofit initiative.

Embracing technology while protecting culture

With projects like these, there are two key considerations that are inherently linked: the importance of co-developing and co-designing AI tools and frameworks with Indigenous communities, and the need to train Indigenous people in coding and development. Doing so gives them real stewardship of such projects, as Dr. Pinhanez outlined in a recent paper he co-authored.

But embracing technology and the desire to protect culture and language are often at odds in Indigenous communities, as Dr. Drea Burbank has observed. Dr. Burbank grew up on Nez Perce lands in Idaho, is trained in Indigenous health and had a nine-year career as a firefighter working closely with Indigenous communities in the US and Canada.

She is now the founder and CEO of Savimbo, an organization which helps Indigenous small farmers and Indigenous communities in the Amazon sell carbon and biodiversity credits. Savimbo also supports them with land rights, literacy and bank accounts. Dr. Burbank has been based near the town of Villagarzon in Colombia since May 2022.

“A minority group that’s fighting to preserve a counterculture will create walls around the culture to try not to dilute it, because the majority culture is automatically going to wipe that culture out,” says Dr. Burbank.

While many of the Indigenous communities Dr. Burbank works with feel technology could contribute to that dilution, she believes it can benefit Indigenous communities. For example, she is looking specifically for partners to help create banking interfaces in Indigenous languages, powered by voice recognition passwords. She’s concerned, though, that a lack of tech savviness would hamper these communities’ ability to properly consent to and govern the use of AI language tools.

“We’re talking about communities where even turning on an iPhone or writing a password is a barrier. It’s very difficult for them to give informed consent for novel technologies,” says Dr. Burbank.

That’s why José Alberto Garreta Jansasoy, Governor of the Cofán Indigenous Reservation in Colombia and a Savimbo advisor, would like technology to come with wider strategies to support the communities more holistically. He believes videos could be a helpful resource for teaching the Cofán language to young people, as it’s currently not widely spoken. He would also like to see resources allocated to Cofán language-specific schools.

“Spanish is more commonly practiced for better communication with outsiders, which has led to the unfortunate consequence of gradually abandoning our native language. Fortunately, we have realized this and are working to reclaim our language,” says Jansasoy.

Fellow Savimbo advisor Ramón Uboñe Gaba Caiga, a community leader in the Waorani tribe in Ecuador, feels optimistic that AI tools for preserving Indigenous languages can have the double benefit of expanding environmental and sustainability knowledge, as so much of that is tied into the language.

“It is very important today that young people can have a digital file where they can know the reality of us, and how we protect biodiversity, territory education and health, to have this information as a database for future generations,” says Gaba Caiga, who speaks Wao Terero, which is only spoken by about 5,000 people.

Reciprocal benefits to AI

Indigenous languages can also help to develop AI further, as Dr. Pinhanez points out. Large language models like ChatGPT have not necessarily been trained ethically, having been fed novels and texts without permission from the authors. Since Indigenous communities would need to actively provide texts and consent to their use, working with them could help to change the status quo when it comes to AI practices. And as Indigenous societies’ belief and reasoning systems differ dramatically from Western cultures, using more of them as stimulus for AI models would help remove some of the limits they currently face when it comes to how reasonable and wide-ranging their responses are.

As Dr. Pinhanez writes: “Documentation and vitalization of Indigenous languages has this unique quality of pushing AI to be better in terms of technology and ethics at the same time.”