This story was originally published by Next City.

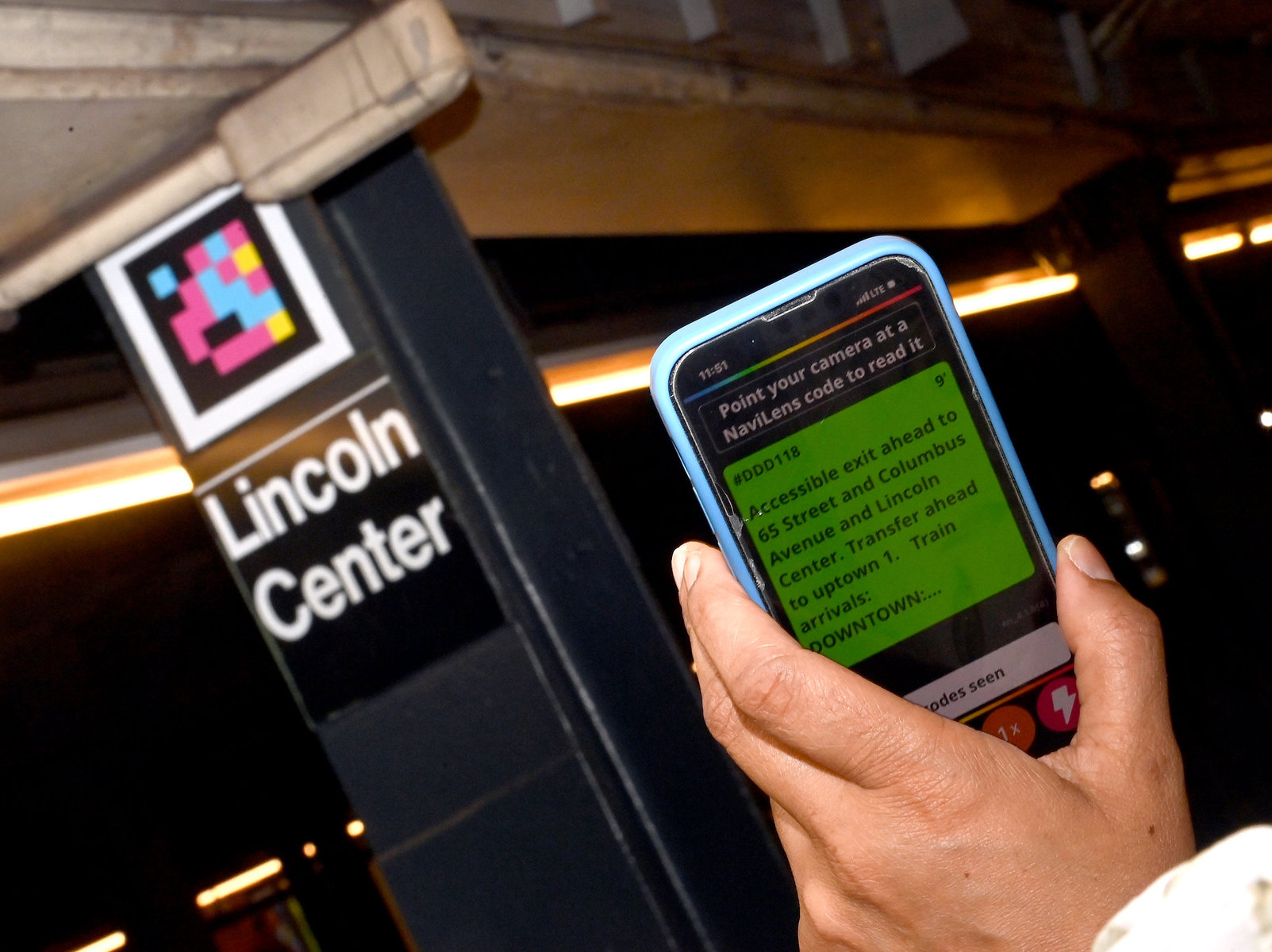

The decal of brightly colored blocks on a black background looks like something straight out of the classic arcade game Space Invaders. But the goal of these codes isn’t to zap aliens — it’s to help people who are blind or have low vision find their bus or train stop.

As anyone who has ever boarded the bus going the wrong way can attest, wayfinding can be challenging for anyone, but people who have sight loss face special challenges.

NaviLens, a tech company based in Murcia, Spain, has developed an app that uses codes posted at bus stops or in train stations to provide real-time navigation via audio and haptic (vibration) cues, directing the user from the elevator in a train station, for example, to a nearby bus stop.

“Despite it being not a huge percentage of our ridership, it’s very important to make sure that we provide accessibility for people experiencing partial or full sight loss,” says Thor Diakow, spokesperson for Metro Vancouver’s transit authority TransLink, which tested the app last year.

To use NaviLens as a rider, you first download the app to your phone. There are two versions: NaviLens for people who are blind or have low vision, and NaviLens Go for general wayfinding. When you open the app, NaviLens uses your phone’s camera to detect and read codes in the environment, reading off bus stop information and providing real-time guidance on how close you are to the stop, for example. Anyone can test out the app by requesting codes to download and print out.

The app detects codes without using GPS or requiring access to Wi-Fi or Bluetooth. NaviLens reports that codes can be read almost instantaneously and at a great distance, making it ideal for wayfinding.

There are many potential applications for the app, says NaviLens project manager Miguel Miñano, through integration with a transit agency’s real-time information system.

By scanning the code, users “will also know the remaining minutes for the coming train, the status of the escalators or elevators and [other] real-time information that changes, but the code doesn’t need to change.”

So far, NaviLens codes have been incorporated into transit systems around the world, including New York City’s MTA.

A promising pilot in Vancouver

Last year, TransLink, Metro Vancouver’s regional transit provider, conducted a pilot using NaviLens at 16 stops within its system. As part of the pilot, 18 people tested NaviLens with the codes scanned a total of 2,792 times, mostly at the New Westminster SkyTrain station.

The pilot was part of a $7 million project to increase accessibility for customers with vision loss. TransLink also added braille signage at all 8,400 of its bus stops and tactile walking surface indicators at 157 locations, the first Canadian transit agency to accomplish this feat.

Richard Marion, an accessibility consultant and member of TransLink’s transit access transit users advisory committee, helped test out the app.

“Where I see it shine would be in more complex interior environments,” says Marion, like metro stations with multiple trains or even municipal buildings that are hard to navigate.

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.There were some challenges with the app, according to Marion and a report from TransLink. To use NaviLens, customers must own a smartphone and be willing to use it to navigate, unlike braille signage and tactile walking surface indicators.

“For someone that’s a bit older like myself that tends to not rely on my cell phone 100 percent of the time out on the street, it’s more of a nice to have,” says Marion. “Other accessibility features are more important to me.”

The six-month pilot was promising, but Diakow says there are no plans to expand it permanently.

“It was mainly focused on these initiatives for the blind or partially sighted, so that’s kind of why we stuck to that for now. But it really helps us understand a broader wayfinding landscape for our system,” he says.

Future efforts might incorporate real-time navigation in different languages to help people from other countries navigate the system (NaviLens offers this feature as well).

The curb cut effect

Better wayfinding for people who are blind or have low vision can benefit all transit riders. As advocates have long pointed out, designing accessible spaces for people with disabilities makes things better for everyone.

It’s called the “curb cut effect”: Curb cuts — those parts of the curb that slope down to the street — make it easier for people in wheelchairs, people on bikes, people pushing strollers, older people, etc. to navigate streets and sidewalks.

To improve wayfinding, Marion recommends that transit agencies focus on consistent and high-contrast signage across a region, so that people with some sight loss can easily distinguish between a no parking sign and a bus stop, for example, even if they don’t read braille. Making bus stops easy to identify would be helpful for wayfinding in general.

TransLink selected NaviLens through a competitive procurement process and paid for the pilot as part of its $7 million initiative to improve accessibility, though Diakow could not provide exact numbers on how much money was spent on Metro Vancouver’s NaviLens pilot.

According to Miñano, most cities that pilot NaviLens do so for free, with the company absorbing the cost of the pilot. Miñano says there should be no barriers to implementing NaviLens, whether it’s a big or small city, because the project can be tailored to the needs of the individual transit agency.

“When we talk about visual impairment, it’s not only about people [who are] totally blind, but this is on a spectrum from the totally blind to [people with] moderate sight loss,” says Miñano.

“So, it’s not [just] a question of metrics, but the commitment of the agency has to be with not leaving anyone behind.”

This story was produced through Next City’s Equitable Cities Fellowship for Social Impact Design, which is made possible with funding from the National Endowment for the Arts.