“America has only three cities: New York, San Francisco and New Orleans. The rest is Cleveland,” the great American playwright Tennessee Williams is more or less quoted to have said (even if the provenance is murky).

Perhaps fittingly, though by complete coincidence, Cleveland is exactly where I began a recent three-month odyssey across the United States of America — to my foreign eyes, at least, a dizzyingly paradoxical and dysfunctional nation that is nonetheless studded with pockets of brilliance, defiance and hope.

I want to share some of those experiences — good, bad and ugly — with you.

Ohio

For someone who had just arrived from Paris, an already wonderful city gilded with the verve of springtime, Cleveland was a serious culture shock. That’s not to say there was anything especially unfamiliar: the glimmering downtown was lined with every known fast food joint under the sun, the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame churned out classic ‘80s rock anthems, and Cleveland Browns football fans were out in force.

But plenty of other things caught me unprepared: On the way to my hotel, I overhear a couple outside Shake Shack explain that they are on a diet and so want no sauce on their burgers. A white supremacist working at a laundromat owned by an old Asian lady lectures me on European politics and warns me to “watch out for the Blacks” in a jarringly friendly tone. On my way out of town, the city’s Greyhound station, filled with the strong scent of urine, has all the charm of a cancer diagnosis.

What won my heart over in Ohio was a completely unexpected little town in the far south of the state along the Ohio River. It was by chance I decided to stay the night (to be extended to two) in Ripley, which I knew nothing about when arriving at the Greenwood Motel. Yet its history was and is astonishing: Ripley was a key stop on the Underground Railroad, a network of clandestine routes and safe houses used by enslaved African Americans to escape to freedom. John Rankin, a Presbyterian minister who arrived in 1821, would daringly cross the river into Kentucky heavily armed to help liberate slaves. His house sits at the top of a hill now named after him.

By day two in Ripley, I was the talk of the town of roughly 1,500 people. At the Dollar General store, I got tied up in a 30-minute conversation with the cashier keen to hear about the world. Traders at the flea market eyed me like a curious antique, rare as it is to receive outside visitors these days. The Indian family running the motel insisted I share a chai with them before heading off. “Come back soon,” they all told me.

Utah

Utah might as well have been a different planet — not least because of the astounding million-year-old Martian red rock filling the canyons in the south.

But before I ventured that way, I visited the breathtaking Salt Lake City, which is surrounded by the snow-capped Wasatch Range to the east and the equally dizzying snow-capped Oquirrh Mountains to the west. It is home to the headquarters of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, which claims to have over 16.8 million followers. When I visited Temple Square, the young Mormon girls volunteering as guides attempted to add me to that number after I asked questions out of curiosity. They kindly answered, showed me their Renaissance-aping art collection, and told me of the humanitarian work the church is doing. But there was one question they didn’t have a good response to: why are all the elders white and male?

Another imponderable question that struck me during my visit was: what would Salt Lake City be without a lake? It’s far from theoretical. In July, the Great Salt Lake reached its lowest level since measurements began in 1875. The lake’s surface area has shrunk to about 950 square miles, less than a third of the 3,300 recorded in 1987. The region is experiencing its driest 22-year period in at least 12 centuries.

I spoke to Ella Sorensen of Audubon’s Gillmor Sanctuary, who has spent her life dedicated to the preservation of the lake and the biodiversity that relies on it — millions of migratory birds stop by the lake every year. One of those species is the red-necked phalarope, which has a unique way of gathering food: it swims in circles in pools of water, causing nutritious particles to rise. Sorensen played a key role in the creation of a $40 million water trust in February for the Great Salt Lake. The awareness of the lake’s value and what would be lost is, thankfully, growing.

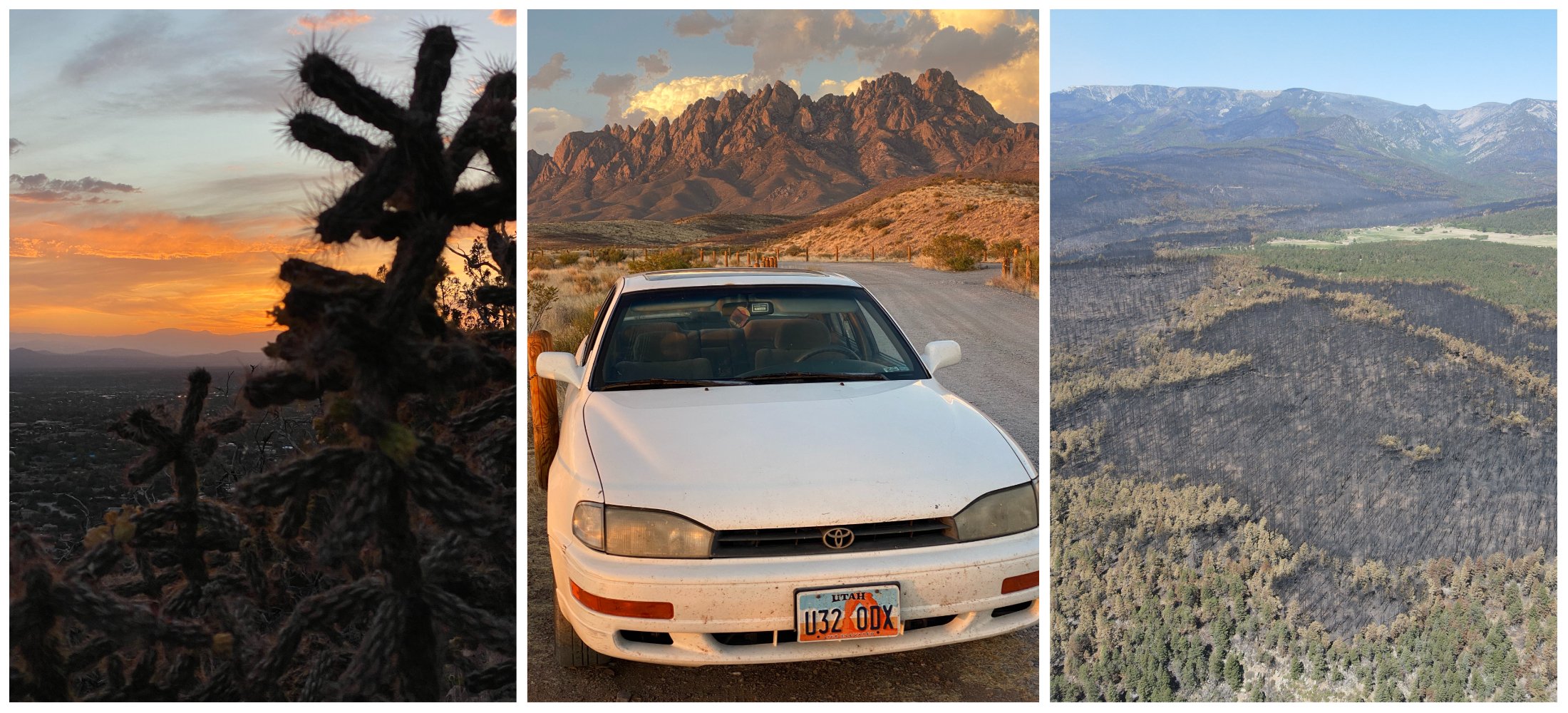

By then, it was time to pick up a set of wheels to continue my journey. I bought myself a white 1992 Toyota Camry for the princely sum of $900. After all, the US pioneered the right-to-repair laws for automobiles, which I figured would likely need to be drawn on. In any case, I always try to buy second hand goods, when possible. Salt Lake City’s thrift stores, too, were a revelation. A tent? $20. An inflatable camping mattress? $5. But most important of all, an endless selection of classic CDs? $1 a go. Ray Charles, Elvis Presley and beyond.

Weighed down by negative news?

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.The first stop on my All American Road Trip was Spring City, a seemingly peaceful town of about 1,000 residents that is on the National Register of Historic Places thanks to its exquisitely preserved Mormon architecture. It was settled in 1850 as Native Americans were dispossessed of their lands. More recently, Spring City has become the hub for a burgeoning “prepper” movement that fears the imminent arrival of doomsday (on certain news days it’s hard to blame them). Many locals have packed up stocks of food and weapons in RVs parked in front of their homes, or if they can afford it, in bunkers along the foothills of the Wasatch Plateau.

However, my lasting memory of Spring City will be one of generosity and hospitality thanks to an elderly Mormon couple, one a potter and the other a painter, who invited me to stay at their home. The wife baked fresh bread for our dinner; the husband cooked up a delicious stew; they grew their own vegetables and raised livestock. It was a different image of Mormonism, one of humble, hardworking self-sufficiency. But perhaps the apex of stereotype-breaking was when the husband pulled out a bag of tobacco and began hand rolling dozens of cigarettes — smoking is prohibited for Mormons — to be given to the incarcerated Native Americans that he would be visiting the next day, as he has for many years.

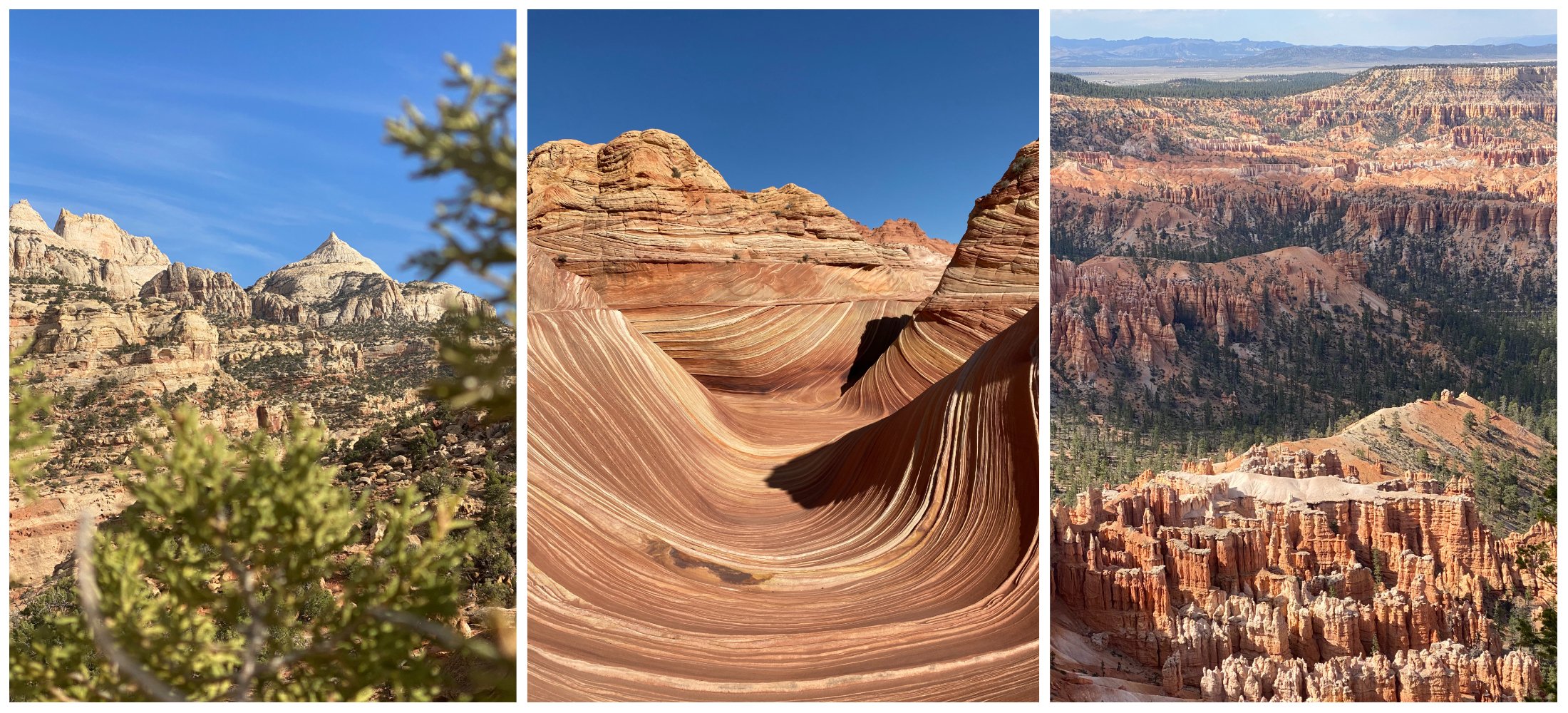

It became easier to understand why those Mormons in Utah believe in a higher power — or indeed, why the Navajo have a spiritual connection with these lands dating back much longer — the further south I went: Capitol Reef was adorned with astonishing red-rock cliffs and canyons; Escalante was home to hiking trails lined with magnificent petrified wood thought to be 35 to 150 million years old; and Bryce Canyon was dominated by crimson-colored hoodoos as far as the eye could see. All the while, the Bureau of Land Management’s dispersed camping policy means you can throw down your tent almost anywhere out in the wild for free and without prior permission. (In Utah, the BLM manages nearly 22.9 million acres of public lands, about 42 percent of the entire state).

Under the Trump administration, there were plans to shrink the Escalante Monument in half and divide the remaining land into small pieces for extractive mining — something that the owners of the nearby Hells Backbone Grill were fiercely opposed to. Opened in 1999, the award-winning farm and restaurant grows its own vegetables, fruits, herbs and flowers, as well as serving up locally-raised, grass-fed lamb and beef. Yet while the joint was undoubtedly a delight — I feasted on pan-seared steelhead trout and then apricot panna cotta – this model is a dime a dozen in Europe and has been for many years, and the fact that so rarely in the US is good-tasting local produce available, whether in restaurants or even grocery stores, was tough to swallow. It’s no surprise then, that more than 40 percent of US adults are obese, compared to around 13 percent globally, with those on lower incomes more likely to be obese.

New Mexico

As I bounded across the Four Corners region, a model of modern sustainable living presented itself. The Earthship Biotecture is a curious community of off-the-grid homes in northern New Mexico built from recycled materials such as aluminum cans, glass bottles, and used tires — at least 2.5 billion of the latter are currently stockpiled in the US. The community grows fruit and vegetables in greenhouses, filters and recycles their own water, and uses small windmills and solar panels for electricity. What’s more, they are decorated with Gaudi-esque glass mosaics made by artists in the Earthship community. The community has been building Global Model Earthships to order and have delivered them all across the US and even to the likes of France, Germany, Mexico and Canada. I can only hope the popularity of Earthships takes off from here. Or at least the ideas behind it.

The need for such resourcefulness was underlined in brutal terms just a couple dozen miles away in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. It is the site of New Mexico’s largest ever wildfire, which began in April and is still ongoing, and has covered more than 340,000 acres of land — an area about the size of Los Angeles. Known as the Hermit’s Peak and Calf Canyon fire, the blaze at its peak forced 27,562 people to be evacuated from their homes. There could scarcely be better evidence that climate change and its deadly impacts have arrived at our doorstep.

I visited the town of Mora, where the fire was at its most devastating. Even from a distance, it was easy to see the large swathes of the once-verdant mountainside that had been charred black. But it’s there, talking to those coordinating the response to the fire, that I learned (and wrote) about a project called Sagebrush in Prisons that enlists incarcerated people to restore fire-resistant sagebrush across several states, rehabilitating not only the landscape, but also the life prospects of those who are among the nation’s most marginalized.

Without wanting to make light of the disaster, other parts of New Mexico were also burning grass, but in an altogether more positive way: The state legalized cannabis for recreational consumption in April, joining 17 others. Sales hit a record high, so to speak, of $40 million in July, with the state receiving 12 percent excise tax on recreational marijuana sales. Advocates say it ensures the product is safer and cleaner, as well as undermines criminal groups. I took it upon myself — in the name of journalism — to test out the product and can confirm it was a safe, amusing experience.

The hilariously-named “budtenders” in Albuquerque explained the nuances of the sensations I was to feel like a sommelier in a Parisian wine bar would. I also discovered that lawmakers in New Mexico have more broadly sought to reverse the regressive impact of cannabis criminalization on minority communities and poor households by automatically dismissing or erasing past cannabis convictions and encouraging social and economic diversity. Yet New Mexico still has a long way to go when it comes to drug policy. Albuquerque, for one, is plagued by fentanyl and meth addiction, and every year hundreds die due to overdoses. Across the US, 108,000 people died of drug overdoses in 2021. If other approaches were taken, I can’t help but think many of those people would be alive.

Texas

Regrettably, Texas is perhaps the leading state when it comes to tragically avoidable deaths, as I quickly found out entering El Paso. For one, those of asylum seekers: In West Texas, from the border post of El Paso all along the Rio Grande to the Gulf of Mexico, dead bodies are showing up. They may not be discovered for months, and in the intense Texan heat and humidity, can quickly become unrecognizable. Migration experts told me that federal policies have exacerbated the tragedy, forcing refugees, mostly from Mexico and Central America, into ever-more perilous crossings. It could all be stopped, they said, if legitimate asylum routes were opened up. But even in this grimmest of situations, I saw reasons for hope. In El Paso, I met the 71-year-old Ruben Garcia, director of Annunciation House, which has been providing food, shelter, legal advice, and crucially, a sense of humanity to migrants for over four decades. I met Eddie Canales, director of the South Texas Human Rights Center, who fills a network of more than 100 barrels of water in Brooks County, Texas, to prevent migrants from dying of thirst, and even reunites the bodies with their families back home — something that simply wouldn’t be done otherwise. I also met Don White, a volunteer for the Remote Wildlands Search and Recovery, who hikes through this harsh ranchland every day, and is often the one to discover the bodies first.

The second group of avoidable deaths in Texas evades definition because it could be literally anyone: a victim of gun violence. After cruising through the state’s remote Big Bend Region, I arrived at Uvalde, where nineteen students and two teachers were fatally shot during a mass shooting at Robb Elementary School in May. As I walked between the shrines, many pictured with the faces of these innocent children who were murdered, I couldn’t help but cry.

No other country in the world kills as many children with guns. As my colleague Michaela Haas reported, regulation of guns is shown to clearly work and reduce deaths. The problem, however, goes beyond fact and into the murky, complicated realm of politics. A few days before, that complexity was made abundantly clear to me when, in the street, I met a retired Native American, Trump-supporting cop, who showed me around his ranch and taught me how to shoot a pistol on his firing range. Friendly and eccentric as this man was – he wore a kilt due to his partly Scottish origins and gifted me a Luke Skywalker figurine – he insisted that comprehensive, tighter gun control was not necessary. We spoke for a couple of hours, but I got the impression that a month wouldn’t have been enough.

Louisiana

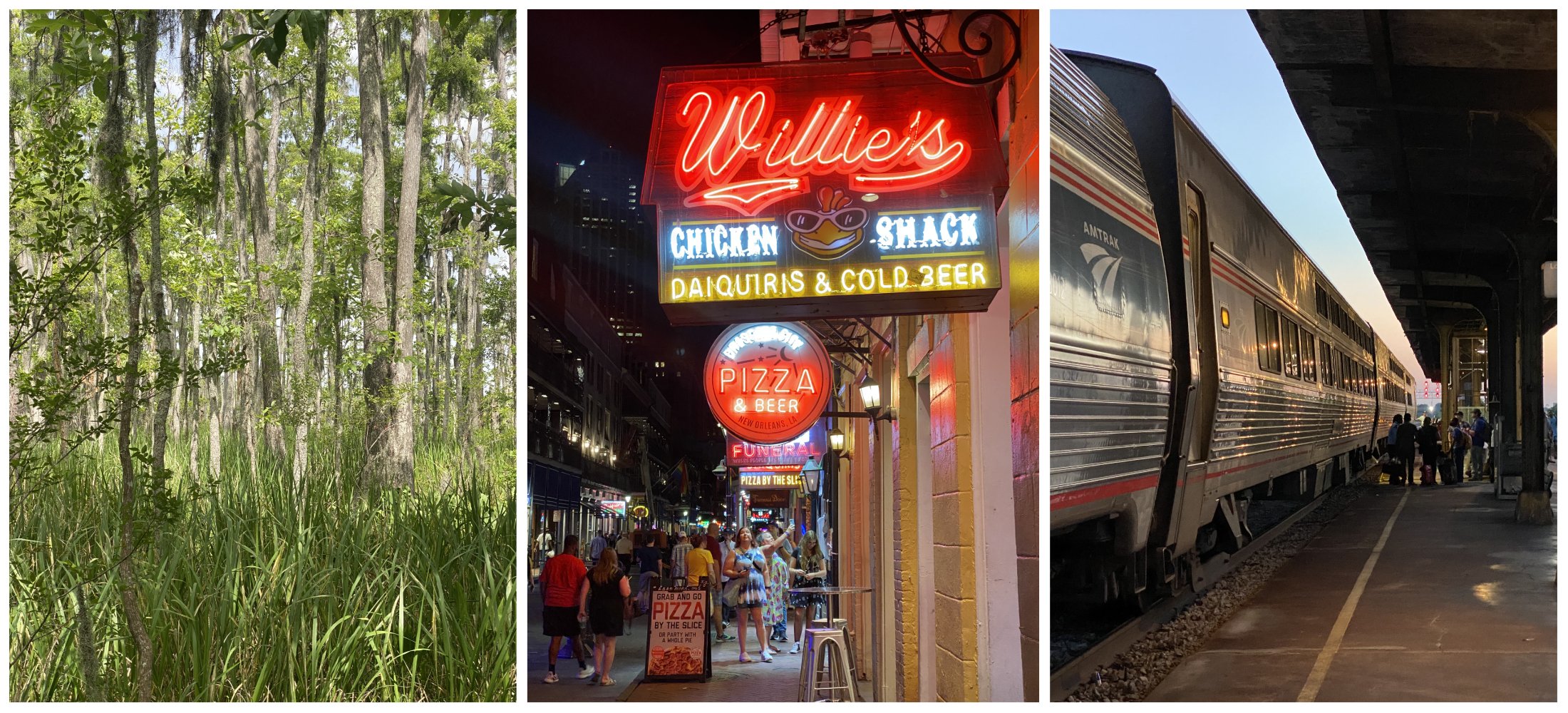

Onwards, I rolled through the sweltering climes of Louisiana, grateful that my car’s AC was holding up, even if the engine took an increasingly long time to start up each time. I’m not sure what was more bearable, the bone-dry aridity of West Texas or the sauna-like humidity of the Gulf Coast. Here, alligators sunbathed on the river beds or with their snouts poking out from the region’s famed bayous. Sadly, these incredible ecosystems are under threat from manmade climate change — which is bringing more severe and regular tropical storms, rising sea levels and coastal erosion — as well as a number of other factors such as oil and gas drilling. As a result, Louisiana is losing a football field of wetlands to open water every single hour.

I took a boat through the beautiful Atchafalaya Basin, the largest wetland and swamp in the US, to take a look up close at what could be lost. It contains at least 250 bird species, including bald eagles, 65 species of reptiles and amphibians, and 100 species of aquatic life. It’s like a slice of the Amazon rainforest. But while the devastating impact of coastal erosion is something I’ve reported on several times before, rarely have I read anything novel to respond to it. That is, until I arrived in New Orleans, where a pair of recent college graduates are recycling glass to create coastal sand. They began in a frat backyard hand-crushing bottles one by one, and have now scaled up to a 40,000-square-foot warehouse. Scientists are currently researching how the glass sand reacts with the natural surroundings in a couple of field tests. I’ll certainly raise a New Orleans-style hand grenade cocktail to the inspiring Greta Thunbergs of the Big Easy.

A little further up the Mississippi, beyond rows of majestic, hundred-year-old oak trees, I found similar signs of progress. The Whitney Plantation, opened in 1803, is a former sugar-cane plantation once home to 350 slaves that is now focused on telling the history and legacies of slavery in the South. Rarely, in my experience, is space given to Black histories from the perspective of those communities. It was a draining experience, taking you through the excruciating realities of life as a slave thanks to detailed archives and testimonies, as well as the acts of defiance by the enslaved. But clearly, there’s a long way to go. Strolling around the Black neighborhoods of Lafayette and New Orleans, often filled in ramshackle, substandard housing, much of the inequalities that began with slavery are still in place. Indeed, I recently wrote about the growing movement for reparations, amid ongoing, widespread racial discrimination across the US. But at least the conversation has begun.

And so, some 6,000 miles later, I reached the end of my road trip. In New Orleans, I sold my car for $100 profit while simultaneously taking part in the circular economy, and jumped on The Crescent, an Amtrak train that runs from New Orleans to New York City. The epic 1,377-mile, 30-hour ride is one of the longest train journeys in the country, passing through more states than any other Amtrak route: 12 states as well as the District of Columbia. I won’t lie, as someone who has taken trains across France, Russia, China, Spain, Japan, Myanmar, Germany, India and beyond, the quality of service needs to improve (I’m looking at you, attendant Kevin). But funding is already on the way: Last year, President Joe Biden announced $66 billion in new financing for rail, which could fuel Amtrak’s expansion across the country and bolster current routes in place. We are big train enthusiasts, of course.

New York

My final call was to be New York City, a place that relies historically and culturally so much on its immigrant communities. But it’s a place that is becoming increasingly unaffordable for those who made it what it is: the $20 bagels; the million-dollar Manhattan apartments; the Brooklyn hipster coffee shops; the McDonalds that are taking over Harlem. Instead, I found the people of New York City to be its redeeming feature, especially in Queens, the most diverse county in the nation. The witty Jewish bookstore owner in Borough Park; the mad Greek priest sitting by a souvlaki stand in Astoria; the seventy something gospel singers at the Mount Neboh Baptist Church in Harlem; the Puerto Rican bar owner Toñita in Brooklyn; and the freewheeling jazz musicians at a park in The Bronx’s Pelham Bay. The people of the United States — for all its flaws, inadequacies and dysfunctions — are what make it great.