If you live in the United States, your home is likely heated by a boiler or a furnace — a little personal power plant in your basement chugging out heat just for you. There are millions upon millions of these heating units, warming individual dwellings one at a time. It’s a highly inefficient system. In fact, it isn’t really a system at all.

In most cities and suburbs, these boilers and furnaces run on natural gas, a fossil fuel often described as “clean” even though it emits carbon dioxide. The U.S. is burning a growing amount of it to stay warm. In New York City, for example, 42 percent of carbon emissions come from natural gas boilers. Finding cleaner, more efficient ways to heat our homes is a climate action imperative.

One solution may lie across the Atlantic, in the suburbs of Paris, where a vast, shared heating source snakes below the ground, pumping carbon-neutral heat from deep beneath the earth into homes — a sustainable system everyone can tap into.

A sprawling solution

In 2015, France committed to being carbon neutral by 2050. Reducing indoor heating emissions would be crucial to achieving this goal. The roadmap to get there relied, in part, on geothermal heat distributed to homes and buildings in suburban Paris through an unusual network known as district energy.

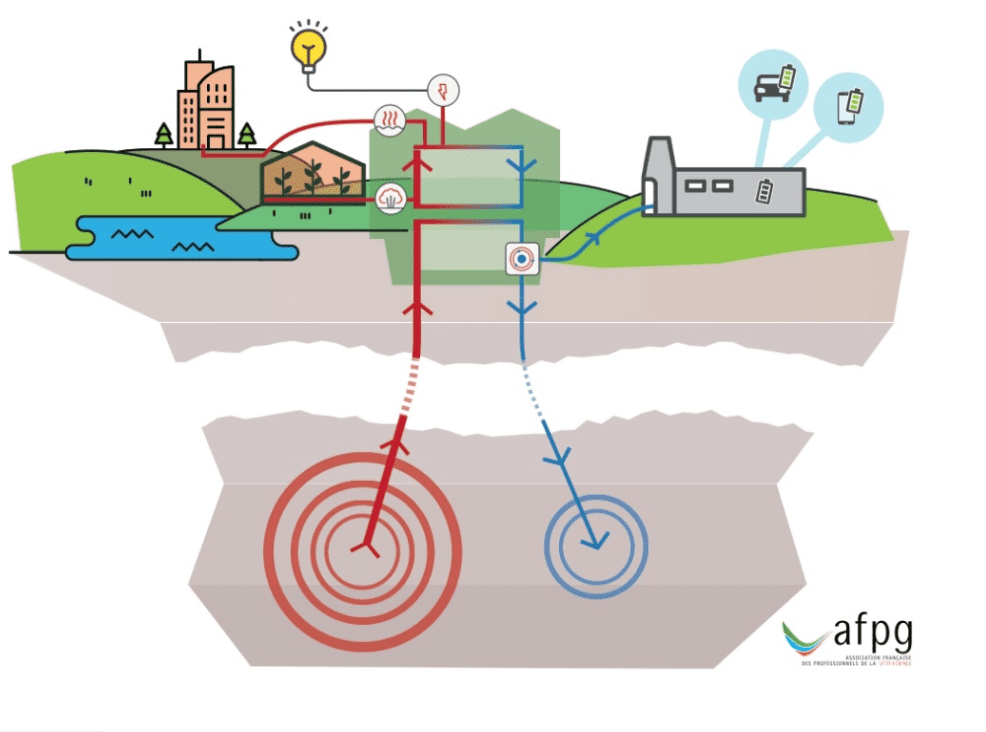

District energy systems produce hot (and sometimes cold) water at a central location, then channel that water through underground pipes to buildings, either heating or cooling them. This eliminates the need for individual boilers and reduces carbon emissions, since producing heating and cooling at a central location is more efficient than generating it one building at a time. The French plan takes this model and makes it even more sustainable by producing the heat with a green energy source: geothermal energy.

Geothermal energy draws water from deep beneath the ground, where it has been naturally heated by the earth, making it a carbon neutral energy source. “In France we know that there are mainly three big regions where there are awesome resources for geothermal,” says Alexis Goldberg, the head of the District Heating Market at ENGIE Solutions. “Île-de-France, Grand est Alsace in the east of France, and Aquitaine in the southwest of France.”

ENGIE settled on Île-de-France, which contains the Paris metropolitan region, as the place to test the viability of its project. Two of the most notable projects in Île-de-France were joint ventures: one in Bagneux and Chatillon, and the other in Arcueil and Gentilly. The Arcueil and Gentilly project launched in late 2015 — just before the Paris climate talks — serving about 7,500 buildings with geothermal heating. At the time, this project was thought of as a way to demonstrate how home heating emissions could be curbed by as much as 60 percent. This project has since significantly scaled up to serve three-quarters of all buildings in those suburbs. Similar in scope, the Bagneux and Chatillon district heating apparatus provides heat to over 40,000 people in that district.

Sharing the costs

The project wasn’t without challenges. One of the big ones was that geothermal sources, even in densely populated Île-de-France, can be far from the homes they’re meant to heat. This requires lengthy distribution systems before the hot water even reaches the district, and disruptive street excavation in order to lay the piping itself. Neither of these two challenges make this type of project impossible, but they do make it expensive. Even with an infusion of upwards of seven million euros in subsidies from the French Environmental Management Agency, it was too costly for any one municipality to pay for alone.

Weighed down by negative news?

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.So, to make the costs manageable, suburbs began collaborating with each other, creating joint ventures that reduced construction costs. This nicely dovetailed with the district energy model itself, which is premised on the notion that sharing a resource, rather than everyone doing their own thing, leads to better outcomes. Built as a collaboration, the system allows the hot water to move through multiple municipalities and into individual buildings.

“Sometimes only a quarter of a city [can] get some renewable energy, but you can make it with a big district heating [system] if you have the resource like in Île-de-France,” Goldberg says.

Despite getting most of their indoor heating through new and more sustainable means, it’s likely that most customers won’t even notice the switch. Jean-Baptise Sivery, deputy director of network heating sales at DALKIA, a subsidiary of Électricité de France, says that geothermal district energy is often connected to buildings where the existing gas boiler sits. This not only makes it easy to hook up to existing buildings, it also makes heating seamless through cold winter days. When the temperature drops to the point that geothermal is no longer viable — at most one-third of the year — the gas boiler automatically keeps the heat flowing.

In fact, the only real change that residents might notice is that their wallets have become a bit heavier. French subsidies for renewables, coupled with the even spread of construction costs over 30-year contracts, decrease energy costs by up to five percent.

The savings on carbon emissions are even more impressive. According to Sivery, for every one equivalent unit of fossil fuel energy used for maintenance of the district heating system, four equivalent units of green geothermal are produced.

News of these successes has spread to communities throughout the Parisian Basin. In 2019, the commune of Champs-sur-Marne successfully crowdfunded an investment in developing geothermal district heating. “[There’s] a real conscience from the citizens to be really proactive in helping the ecological transition in France,” Goldberg says.

There’s no better public-facing example of this proactiveness than the proposed geothermal district heating system for the Paris 2024 Olympic and Paralympic Village. The geothermal heating and cooling for the Olympic Village is a show of France’s commitment to renewable energy. It’s also a vision of what’s to come for the country’s green energy prospects. If the Olympic project is successful, it could spark geothermal district heating projects across the country.

In an August press release, Wilfrid Petrie, executive vice president of ENGIE Solutions, said that “geothermal energy will therefore take the honors by becoming an Olympic energy for the athletes.” Perhaps the athletes will carry home interest in renewable energy along with any medals they pick up in France.