Next to Washington D.C.’s Piney Branch Parkway, right across from where that road intersects with 17th Street NW, CSO-049 serves the Rock Creek Sewershed, a 2,329-acre area of Washington D.C., with a diverse, mixed-income population of close to 90,000.

CSO-049 is the end of a pipe, part of D.C.’s sewer system. In an average year, 39.73 million gallons of combined stormwater and raw sewage flow out from CSO-049, dumping feces-polluted water into Piney Branch, which flows into Rock Creek just upstream from the Smithsonian’s National Zoo, and historic neighborhoods like Mount Pleasant, Dupont Circle, and Georgetown.

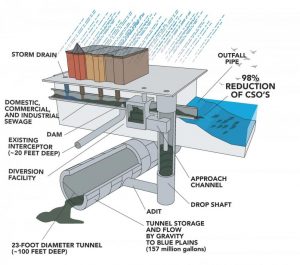

But most of the time, CSO-049 is dormant. The acronym “CSO” stands for “combined sewer overflow,” and CSO points like these are a feature of combined sewer systems designed and built mostly more than a century ago. In combined sewer systems, storm drains capture rainwater runoff — and any pollutants it picks up along the way — and sends it into the same sewers that collect wastewater from homes and businesses. On most rainy days, it all flows to wastewater treatment facilities that are supposed to remove toxins and other pollutants before releasing it back into natural bodies of water.

During heavier rainfall, however, combined sewer systems can’t handle the volume, sending the mixture directly out from overflow points like CSO-049, one of around 50 such overflow points in the District. And today, because of climate change, heavy storms are occurring more frequently, causing more of these overflow incidents in cities that have combined sewer systems.

According to the Environmental Protection Agency, around 860 cities across the country with a combined population of 40 million people have combined sewer systems, including most major cities, especially the older cities of the Northeast and Midwest like Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Boston, Chicago, Baltimore and New York. (With Hurricane Ida’s remnants dumping more than 7 inches of rain in some parts of the city, most of New York’s waterways are currently contaminated with sewage and on no-swim advisories.) The agency also notes, however, that most communities that experience combined sewer overflows have a population of 10,000 or fewer. In 2000, the EPA estimated that combined sewer overflows alone were responsible for releasing 850 billion gallons of untreated wastewater and stormwater every year directly into bodies of water where people swim, canoe, fish or otherwise spend time.

Most cities facing this challenge have responded using what’s known as “gray infrastructure” — digging massive new underground tunnels or enlarging existing ones to capture and store stormwater until it can flow to wastewater treatment plants. An alternative, which a growing but still small number of cities are starting to embrace, is “green infrastructure” — rain gardens, bioswales, tree trenches, permeable pavement, green roofs and other forms that combine old and new technology to absorb more rainwater where it falls.

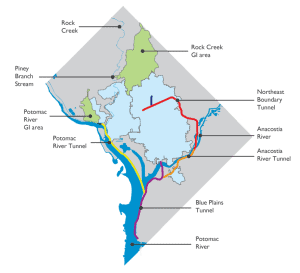

D.C. has already spent or committed nearly $2 billion over the past decade to building gray infrastructure, building massive tunnels deep beneath the Anacostia and Potomac rivers, as large as the tunnels that carry the region’s metro trains. But the District recently marked a major milestone in its gradual embrace of green infrastructure, declaring its first green infrastructure pilot project a success and shifting to a hybrid green-gray infrastructure approach for the final phases of its court-mandated, $2.7 billion stormwater management plan known as the Clean Rivers Project.

“We’re always learning from this whole process,” says Carlton Ray, director of the Clean Rivers Project. “Every project we’re learning from it and presenting papers in different places to push along the industry about where we should be heading with green infrastructure.”

There are so many ancillary upsides to green infrastructure that it can seem befuddling why more cities across the country haven’t yet fully embraced the approach for managing stormwater, especially in this climate change-induced era of more frequent and harder-hitting big storms.

Worried about urban heat island effects making poor and particularly Black or Latino dangerously hotter than other neighborhoods? Green roofs, bioswales, and tree trenches can help with that.

Worried about properties in Black neighborhoods being undervalued because of historical and ongoing racism in real estate and banking? In Philadelphia, a 2016 study commissioned by the Sustainable Business Network of Greater Philadelphia found green infrastructure produced a ten percent increase in home values nearby, with 58 percent of Philly green infrastructure projects in low- or moderate-income areas.

Worried about billions or trillions of dollars in public procurement contracts going to firms not based locally or not representative of a city’s local population? The same Sustainable Business Network study conservatively estimated Philly’s green infrastructure industry as of 2016 represented at least $146.8 million in annual revenues, supporting 430 additional jobs and generating $860,000 in tax revenues for the City of Philadelphia.

Green infrastructure projects are generally a better fit for smaller firms and those owned by women or people of color, who because of structural barriers have more difficulty accessing large amounts of credit to be able to compete for “gray infrastructure” stormwater management projects.

Lawsuits brought by the EPA against cities have helped push green infrastructure to where it is today. The EPA began regulating combined sewer overflows in 1994, under authority of the 1972 Clean Water Act. Over the years, the agency has used this authority to file court cases against local governments and utilities over combined sewer systems. The cases typically conclude with court-ordered “consent decrees” that mandate local governments or water utilities to set and meet combined sewer overflow reduction goals and timelines.

Philadelphia’s landmark 2011 consent decree committed the city entirely to green infrastructure to reduce the amount of stormwater flowing into its sewer system. The rationale was that the city’s existing combined sewer system was so old, it would cost much less just to reduce the amount of stormwater flowing into it than it would to upgrade or enlarge its sewer tunnels. The city has since installed more than a thousand acres of green infrastructure.

But Philly has been an outlier in that regard. Most cities promise only to use gray infrastructure in their consent decrees. Out of at least 84 civil cases or settlements the EPA has brought against local governments or utilities under the Clean Water Act, nearly all of them having to do with sewer overflows, only 17 include green infrastructure as part of consent decrees.

Partly inspired by Philadelphia, in 2015 Washington, D.C. actually amended its consent decree with the Environmental Protection Agency, originally signed in 2005, to allow for green infrastructure alongside traditional gray infrastructure.

But even after it did that, the District’s water authority still wasn’t sure how much green infrastructure it needed to build, not to mention whether or not it could get that amount built within the timeframe necessary to meet its overall court-mandated targets for stormwater reduction — reducing CSOs within the district 96 percent by 2030.

Weighed down by negative news?

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.With no experience building green infrastructure and only a few examples like Philadelphia to point to back in 2015, D.C. Water set up a pilot project in a section of the Rock Creek Sewershed.

The pilot project covered an area of around 162 acres of the sewershed, about 40 percent of which was considered impervious surface, meaning pavement or other hard areas that don’t absorb water. The project set a target to convert around 20 acres of the area into green infrastructure, including curbside rain gardens, permeable parking lanes, permeable sidewalk pavers, “landscape infiltration gaps” and even new street trees. Two small green infrastructure parks were also built as part of the pilot. D.C. Water began closely monitoring rainfall and sewer flow volumes in the pilot area shortly before and after construction began.

Green infrastructure projects may be smaller and cost less up front than gray infrastructure, but they require more coordination with other utilities and agencies like departments of transportation. There’s also having to navigate the thorny landscape of engaging residents to determine where to place rain gardens and bioswales or which alleyways to tear up and replace with permeable pavement. As Ray notes, those changes weren’t always welcome, or at least required careful coordination, especially if it involved temporary or permanent loss of parking.

“We needed to be a little bit cautious about it,” says Ray. “There were certain residents who did not like it and did not want it. But the vast majority were very supportive.”

As a result of its pilot project for the Rock Creek Sewershed, D.C. Water did end up reducing the gray infrastructure it needed. It was originally going to build a 9.5- million- gallon storage tank — about the size of 15 Olympic swimming pools — as part of its plan to reduce outflows from CSO-049, but, according to Ray, the authority ended up needing to build only a 4.2-million-gallon tank.

Funding green infrastructure is a whole other question. D.C. Water has been issuing tax-exempt municipal bonds to fund construction of its gray infrastructure. The bonds get paid back over time through a combination of normal water and sewer fees plus a new “impervious area” charge that also serves to incentivize private property owners to build green infrastructure where possible on their properties in order to get a discount on that charge.

To finance its first green infrastructure pilot project, D.C.’s water authority borrowed $25 million using a more complex tax-exempt municipal bond called an “environmental impact bond,” which the EPA called a “first of its kind.”

For typical municipal bonds, the borrower simply states what it will do with the borrowed funds, when it will pay it back and how much interest it will pay to investors. In this case, the bond agreement included a performance-based bonus structure. If the green infrastructure didn’t perform as well as expected, the investors would pay an extra $3.3 million to D.C. Water. As Ray explains, the rationale was if the green infrastructure underperformed, the investors would partially compensate D.C. Water for now needing to build more green or gray infrastructure than originally anticipated..

On the other hand, if the green infrastructure performed better than expected, the water and sewer authority would pay the investors $3.3 million. The rationale in that case was the water and sewer authority would more than cover that amount in the savings it would end up generating thanks to the lower cost of combining green infrastructure with gray infrastructure versus an all-gray approach.

In the end, the green infrastructure D.C. Water built for its Rock Creek area pilot project performed as expected, which meant there was no performance-based payment going either direction. D.C. Water repaid the investors the $25 million earlier this year, having paid only a market rate of interest for tax-exempt municipal bonds in the meantime.

According to Ray, the environmental impact bond was necessary to allow D.C. Water to share the risk of green infrastructure with investors. The risk was whether the amount of green infrastructure the water and sewer authority could build within a certain timeframe would reduce stormwater flows into the sewer system by a sufficiently large amount that would justify reducing its use of gray infrastructure. It did, and so for the next ten years, DC Water will borrow and spend another $150 million on green infrastructure through its conventional municipal bond offerings. (It is also spending an additional $850 million on traditional gray infrastructure.)

“The whole point of the [environmental impact bond] model is to prove this is the right way to spend government resources, and once that’s been proven it should be adopted as the new status quo,” says Beth Bafford of Calvert Impact Capital, one of the two investors in the environmental impact bond. “The whole point is to shift behavior.”

This story was originally published on Next City. It is part of the SoJo Exchange from the Solutions Journalism Network, a nonprofit organization dedicated to rigorous reporting about responses to social problems.