Years ago, while working in Uganda on an emergency relief program, Adama Sanneh had an epiphany.

“I had this strange feeling,” he says. “I think I questioned myself whether I was on the wrong side of history.”

Born and raised in Milan to a Catholic Italian mother and a Muslim Senegalese-Gambian father, Sanneh had always reveled in diversity, adventure and knowledge. But while working in East Africa a realization dawned on him: his knowledge of Africa, like so many people’s, barely scratched the surface of the continent’s reality.

He realized that information about Africa’s diverse languages, colorful cultures, lively politics and over one billion citizens was scarce. What’s more, much of the information that was available came from a Western gaze through the prisms of foreign journalism, academia and entertainment. So Sanneh set out to transform Africans from “passive knowledge consumers to active knowledge producers.”

Their primary tool? Wikipedia, the world’s most widely used reference compendium, and one of the few spaces where Africans can directly write and edit the story of their own continent. Wikipedia’s English website attracts an average of around seven billion page views monthly, making it one of the most visited websites in the world.

And yet, it suffers from a paucity of information about Africa. There’s more information about the country of France than the entire continent of Africa on Wikipedia, says Sanneh. So, since 2018, the WikiAfrica Education initiative has been working to change that by enlisting and organizing a new generation of Africa-based Wikipedia editors. Funded by the Moleskine Foundation, of which Sanneh is cofounder and CEO, the WikiAfrica Education initiative is a boldly creative attempt to decentralize Wikipedia — and, in turn, knowledge of Africa — through contributions from those who know the place best.

Weighed down by negative news?

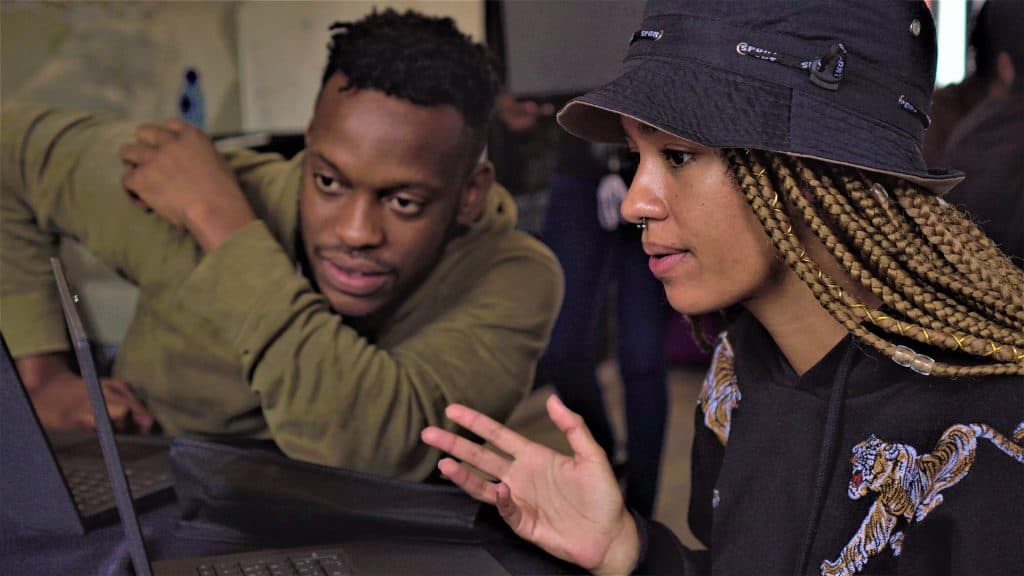

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.AfroCuration, the initiative’s flagship event, holds edit-a-thons where youths edit and create encyclopedic content for Wikipedia in both English and Indigenous languages. The first event took place in October 2019. Over 120 students aged 15 through 18 set out to write Wikipedia profiles about South African history-makers, some of whose biographies were absent from the website, and some, like anti-apartheid activists Winnie Mandela and Steve Biko, that needed expanding.

The edit-a-thons were held at the Constitution Hill Trust in Johannesburg, a former prison complex now transformed into a cultural heritage site. Iconic South Africans such as activists Justice Edwin Cameron and Dumisa Ntsebeza were on hand to impart their first-hand knowledge of South Africa’s constitution and history to the participants. Then, armed with this knowledge, the youths formed working groups to create and expand Wikipedia entries about the protagonists of their country’s democracy.

“These young people had the chance to, first of all, go there and learn about the constitution through the voices and stories of incredible people like Judge Edwin Cameron, who is the former constitutional judge in South Africa,” Sanneh recalls.

Strategic partnerships with groups like the Constitution Hill Trust have been crucial to the endeavor’s success. Other partners included the South Africa Wikimedia chapter Wikimedia ZA, which provided technical assistance and language editors, and BRIDGE, a non-profit organization dedicated to improving teaching and learning in the country. “We saw that there was alignment with our work on constitutionalism and [BRIDGE’s] work on education,” says Lwando Xaso, a historian and constitutional lawyer at Constitution Hill Trust.

With the help of these groups, participants were educated about democracy, freedom and constitution-making, and taught how to translate what they learned into 112 entries in isiZulu, isiXhosa, Tshivenda, siSwati, Sesotho and Afrikaans, as well as expand existing English entries.

The second AfroCuration event, themed “Writing Black Women into History,” was held in partnership with Afropunk Army, the volunteer arm of the global music Afropunk Festival, in Johannesburg on December 29, 2019. At that edit-a-thon, 70 volunteers aged 18 and 25 created 71 new entries for women, from executive director of UN Women Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka to South African jazz legend Letta Mbulu.

“I remembered thinking, what an amazing, amazing initiative,” says Perry-Mason Adams, an Afropunk volunteer who witnessed the event. “What a way to use and preserve the language. So for me, it was a breathtaking initiative.”

Inspired, Adams registered to participate in a future AfroCuration event. But when the pandemic struck, WikiAfrica’s boisterous, in-person edit-a-thons shut down. The endeavor went remote, and pivoted to translating Covid-19 articles into Indigenous African languages. Volunteers were sourced through an Africa-wide social media campaign called “The solution will not be televised.”

Adams, 29, dove into the effort, seeking help from his mother and community in the capital city of Pretoria as he attempted isiZulu and Xhosa translations remotely. “I did the article in collaboration with my mom,” he recalls. “She helped me translate the contents into isiZulu. I’d translate and she’d read, proofread the stuff for me and be like, ‘Okay, this sounds right. Let’s put that.’” For Xhosa translations, he got help from native speakers in his community. “I learned a lot and it made me appreciate the language,” he says.

Other youths had similar experiences. In Tamale, the capital city of the Northern Region of Ghana, 27-year-old university student Hajara Baba is using her contributions to have her native Dagbani language, with over three million native speakers, internationally recognized. (Her efforts highlight one of the less appreciated benefits of Wikipedia: according to Nigerian linguist Opeyemi Ademola, because of the site’s vast reach, the mere presence of language on it has a multiplying effect on that language’s use on other platforms and websites.)

Last year, Baba translated Covid-19 articles into Dagbani. She and Adams are among the 390 volunteers from across Africa who have produced 145 new articles about the virus across 16 African languages, amassing over a million views.

On Wikipedia, there is a low barrier to entry for Indigenous African languages. “It’s much easier to upload an entry in Venda or in Yoruba or Zulu compared to doing the same thing in English,” says Sanneh. “The scrutiny that you have in English is higher.” However, citation poses an issue. “I think from a legal perspective, there is a need to widen what is considered a legitimate source for citation for Wikipedia,” says Xaso, also the program curator, “because in Africa, oral history is just as important as what’s found in textbooks. You’d find that Indigenous forms of knowledge are being excluded because they do not fit a Western idea of what a legitimate source is.”

In spite of this, Sanneh’s dream of expanding knowledge about Africa, as told by Africans, is becoming a reality one entry at a time. “Our vision is to say that, through technology, young people will have enough access to resources to check in their own language, to really think about their own lives and build a greater life and become the citizen that they want,” he says.