When the newly renovated Willie “Woo Woo” Wong Playground opened in San Francisco’s Chinatown neighborhood in February, its sand play zones and abstract Dragon- and Phoenix-themed climbing structures came alive with shrieking kids enjoying a welcome respite from months of coronavirus lockdown.

Today, in countries around the world, children are leading more structured, indoor-oriented lives than ever before — one British study found that kids spend just four hours per week outside, half that of their parents. This has only worsened during the ongoing pandemic. And when kids do play outdoors, it is increasingly within the safe, controlled confines of a playground. Fading are the days when children were turned loose in a world of dirt, bugs, and sticks and rocks that could become swords or building blocks with a bit of imagination.

But the colorful play structures that dot suburban neighborhoods are full of fixed synthetic objects that leave little space for imagination. As parents and playground designers learn more about the importance of open-ended outdoor play, so-called “natural playgrounds,” like the Willie “Woo Woo” Wong Playground, have emerged to deliver the benefits of nature in a more controlled space.

What is a natural playground?

“A lot of times a natural playground is defined by what it’s not,” says Mike Salisbury, a landscape architect and lead designer at Earthartist Planning and Design. For example, Earthartist’s “playscapes” are designed to avoid being static or overly programmed. Nor are they manufactured en masse and sold unit by unit like most public playgrounds — which, for all the excitement they promise, are designed to guide and manage movement in a way that minimizes opportunities for unscripted play.

Missing out on free play has consequences for healthy development. Research shows that children who spend more time engaged in free play during their formative years are more likely to contribute to their families and communities and less likely to have behavioral problems later in life. Free play has more immediate benefits, as well — one Scandinavian study demonstrated that children who play in unstructured environments develop better motor skills than kids on programmed playgrounds.

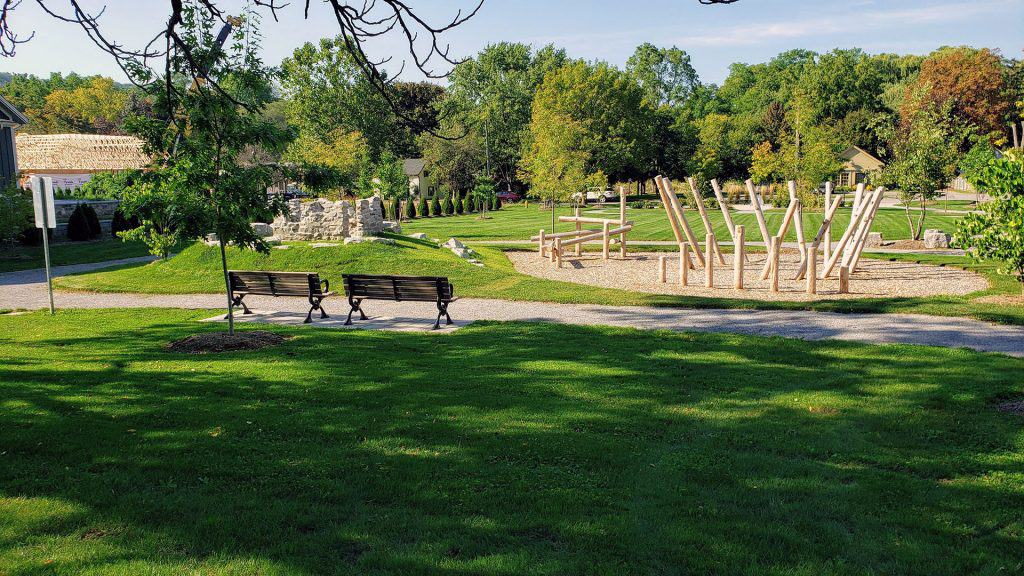

Natural playgrounds are designed to nurture this free play. They tend to feature movable materials like dirt, sand and water. When natural playgrounds include play structures, they’re often abstract, their use not immediately apparent. A structure that looks like a larger-than-life fish to one kid might become a spaceship or a prehistoric cave in the mind of another. “When we’re doing a structure, whether it’s a tower or a giant animal … part of the design process is abstraction,” says Nathan Schleicher, lead playground designer at Earthscape. “It is always about how many opportunities a kid has to use their imagination with the space.”

At Earthscape, Schleicher says the design process is collaborative. Designers start by working with city or park administrators to develop a vision for the space that honors the local landscape. “It is very much about doing design every single time so that the space is really imbued with a unique character,” Schleicher says. Once the team has a vision, it uses natural materials to produce the features of the playgrounds — from boulders and towers for climbing to the abstract animal-shaped play structures that distinguish their work.

The best of both worlds

The loose parts and changeable environments that characterize natural playgrounds invite constructive play which naturally appeals to children’s active brains. Studies show that kids spend twice as long playing on natural playgrounds as they do on traditional playgrounds.

“These types of playgrounds really encourage [kids] to stop, to think, to figure things out — using the executive functioning part of the brain,” says Dr. Regine Muradian, a clinical psychologist specializing in children and adolescents. Executive function skills are those that enable us to plan, remember instructions and multitask, and they can only be developed through experience and practice. According to Dr. Muradian, using a combination of motor and cognitive skills to traverse abstract play structures also helps kids hone their executive function, critical thinking and conceptualization abilities.

Essentially, these spaces mimic the benefits of the wilderness environments that kids used to play in without sacrificing the safety or hygiene that many modern parents wring their hands over. “The beauty of [a natural playground] is that we’ve taken the same level of engagement that you might get climbing a tree in the forest … and introduced it into a formal environment that meets the requirements of safety,” explains Schleicher.

As children spend more time indoors, especially during the pandemic, Muradian has seen increases in impulsivity and frustration. Kids are also growing fatigued from hours of screen time. Natural playgrounds can help mitigate these problems, even for families in urban or suburban environments. “I think that there’s a growing idea that we can do better for our children’s spaces,” Schleicher says.