Ambrose Place is one of Edmonton, Alberta’s best-known affordable housing developments for people transitioning out of homelessness. But what most Edmontonians don’t know about Ambrose Place is that, right underneath it, is a massive, $1 million subterranean parking garage that sits empty and unused.

“Existing parking regulations required that Ambrose be constructed with roughly 50 parking stalls, despite the fact that virtually none of the 42 residents of Ambrose were anticipated to own vehicles” Anne Stevenson from the Right at Home Housing Society told Edmonton’s City Council at a hearing on Edmonton’s parking regulations. Stevenson described the nonsensical nature of the city’s current parking requirements. “Instead of being able to reduce rents or hire additional staff to support residents, these tens of thousands of dollars are being spent paying for a parkade that sits vacant for the majority of the time.”

Like almost every municipality in North America for the past fifty years, Edmonton has told businesses, developers and landowners how much parking they must provide on their property. Want to build a neighborhood café? You’ll need one parking space per 50 square feet. How about a housing development for seniors? That’ll be one space per unit. A go-kart track? Two spaces per cart. A bowling alley may require up to five spaces per lane. Parking minimums, as these policies are called, are premised on a seemingly rational theory: if businesses and residences don’t give people somewhere to put their cars, parking chaos will surely ensue.

Last month, however, Edmonton implemented a radical rule change: going forward, other than mandatory accessible spaces, no property would be required to provide any parking whatsoever.

The rule change made Edmonton the first major Canadian city to eliminate off-street parking minimums citywide. As an urban planning tweak, the move may seem arcane. But Edmonton’s policy change is a very big deal — a radical rejoinder to the notion that cities need ample parking. Its results will be closely watched by officials across the continent.

“We are leading the way in passing a policy that contributes to changing the way our city will grow from here and what long-term sustainability looks like here in Edmonton” Mayor Don Iveson said at a press conference. “This policy removes barriers for new homes, and for businesses, and improves choice and flexibility in how businesses and homeowners meet their future parking needs.”

An unlikely pioneer

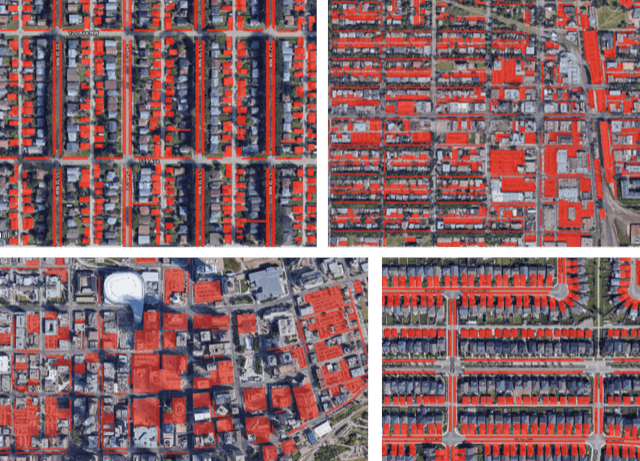

At first glance, Edmonton doesn’t seem like the type of city that would champion progressive urban planning. It’s the gateway to northern Alberta’s oil sands industry, a major source of fossil fuels. It is also home to Canada’s largest shopping mall and the biggest parking lot in the world. The city boomed at a time when car-oriented urbanism was ascendant, and developed accordingly, with vast stretches of asphalt parking lots. The result is that today, Edmonton has 50 percent more parking than it needs. Even at peak hours, on the busiest days of the week, half of the parking the city has forced landowners to build over the years is empty of cars.

This oversupply is not unique to Edmonton. Across North America, cities suffer from too much parking. Sacramento, California has an average oversupply of 65 percent. Seattle has a 23 percent oversupply at peak utilization. A 2014 study of 27 mixed-use districts across the United States found that, on average, parking is oversupplied by 65 percent.

This is because, in general, parking minimums do a poor job of estimating parking demand. They’re a top-down policy tool that doesn’t accurately account for individual circumstances. Does the camping gear retailer whose customers mostly arrive on mountain bikes need as many parking spaces as the furniture store? According to parking minimum rules, it very well might. Rather than letting property owners decide how much or how little parking they need based on their context, location, or target market, parking minimums forcibly decide for them. This type of inefficiency comes at a significant cost.

How much? The cost of a single parking space can range from $7,000 to $60,000. Using Edmonton’s 50 percent oversupply and a conservative cost per space of $10,000, this represents close to $200 million in pavement that, at any given time, nobody’s using. If you’re a new business operating on tight profit margins, having to provide numerous parking spaces can make or break your project. And if you do manage to meet minimum parking requirements, the cost of parking doesn’t just disappear. It gets passed down to consumers in the form of higher rents, groceries, gym memberships and lattes.

Weighed down by negative news?

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.From a land use perspective, the more parking we build, the more spread out our cities become. The more spread out our cities become, the more dependent we are on cars. This means higher emissions, declining health, costly spending on new roads, schools, sewer lines and services at the fringes, higher taxes, more traffic and less investment in public and active forms of transportation.

With such a long list of negative externalities, the casual observer may wonder why every city hasn’t done away with parking minimums by now. Some have, but to varying degrees. More cities than ever are making moves to eliminate them, but in most cases, the hold up can be summed up by two words: car culture.

Car culture is the implicit deference to personal automobiles above all other modes of transportation. It’s a hidden force in our society at the root of policies like parking minimums. It’s the reason your dentist may offer to validate your parking fee, but not offer you a bus ticket. Life without cars is unimaginable because we’ve made it so, but our reliance on cars is not inevitable, as places like the Netherlands, Copenhagen and Paris have shown.

The road to livability

Edmonton’s journey from car-oriented city to forward-thinking urban planning pioneer didn’t happen by accident. A number of players and factors converged to get us here.

Credit is due to Edmonton’s city planners, who have been de-prioritizing parking for the last ten years. A series of incremental changes saw parking requirements for single-family homes reduced from two spaces to one. Reductions for properties located close to transit and LRT lines were expanded, and parking requirements were lifted for restaurants along key main streets.

In conjunction with other policy changes, such as eliminating single-family-only zoning, Edmonton’s forward-thinking leadership and administration cultivated a culture of progress that sees urban evolution as foundational to building a more competitive city. “During our City Plan and Connect Edmonton engagement, they [Edmontonians] told us, you told us, that you want a vibrant and walkable and compact city, and policies like this help deliver just that, over time,” said Mayor Iveson.

Nevertheless, City administration recognized that parking is a hot-button topic, and, anticipating the potential for pushback, performed numerous studies and launched a highly effective engagement campaign. The messaging was consistent and clear: removing parking minimums is about choice — the city wasn’t taking away parking, it was stepping aside so property owners could decide for themselves how much parking they need. Removing minimums was framed not only as a progressive urban planning innovation, but as a pragmatic, data-driven decision that would eliminate waste and costly oversupply.

In the end, developers, community members, local businesses and activists all aligned. City council voted unanimously to enact the proposal on June 23. The effects of the policy will take time to bear fruit, but other cities that have eliminated parking minimums may offer a glimpse into Edmonton’s future. Starting in 2012, Seattle began reducing or eliminating parking minimums in most of its central neighborhoods. Afterward, developers built 40 percent less parking than had previously been required of them. The result? Some 18,000 fewer parking spaces, saving an estimated $537 million.

Some Covid-19 interventions have given us insight into what a post-parking world might look like as parking spaces are being reclaimed for public spaces, patios and mobility lanes. Although it’s been less than a month since parking minimums have been removed in Edmonton, keen developers are already planning parking-free housing projects.

For future businesses, residents and developments like Ambrose Place, Edmonton’s decision to remove parking minimums means more space for people rather than personal automobiles. Despite its history of auto-dependence, Edmonton is proving to be an incubator of progressive urban planning policies, (un)paving the way for municipalities across the county.