The menu at the diner where Amy Nelson likes to take a break from work is notable for its side dishes, including caramelized bananas, cinnamon apples and mushrooms and onions.

Each can feed an appetite in its own right. And together with an entrée, they add up to breakfast.

That’s much like the radically new way Nelson and a small number of other pioneering students have been experiencing college.

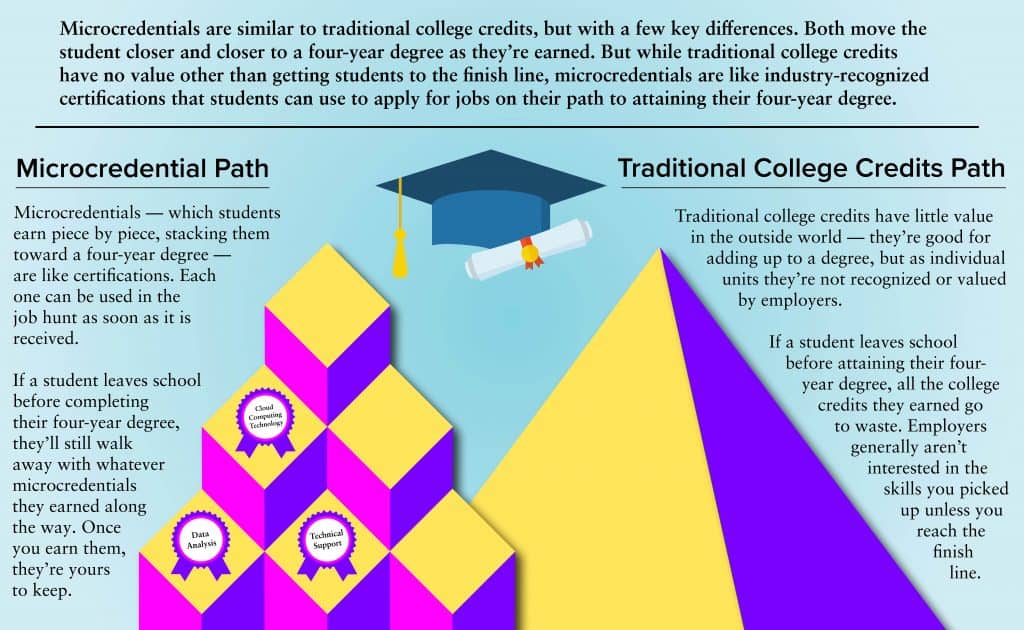

First they get a credential in a skill they need, then another and another. Each of these can quickly pay off on its own by helping to get a job, raise or promotion. And they can add up over time to a bachelor’s degree.

“Even if I chose not to finish, I would still have these pieces and I’d say, ‘Look what I’ve done,’ as opposed to, ‘I have two years of college’” but nothing to show for it, said Nelson, who works as an information technology consultant and hopes to move into an administrative role.

The concept, known variously as “stackable credentials” and “microcredentials,” she said, “almost seemed too good to be true.”

That’s one of the reasons it’s been painfully slow to take off: Consumers have trouble understanding it. Even after she began the program, Nelson didn’t entirely get it. Then she started earning high-demand industry certifications, in rapid fire, in subjects such as technical support, cloud technology and data analysis on her way to her bachelor’s degree in data management.

“I don’t think it really dropped on me until I sat down to update my resume,” she said. That’s when Nelson realized that each of those certifications had already increased her value on the job market.

Now the toll being taken on the economy by the coronavirus pandemic is giving microcredentials a huge burst of momentum. A lot of people will need more education to get back into the workforce, and they’ll need to get it quickly, at the lowest possible cost and in subjects directly relevant to available jobs.

The number of people in the same stackable information technology bachelor’s program as Nelson, offered by Western Governors University, has more than doubled since the start of the pandemic, from 4,410 in March to 10,711 in May, the online nonprofit says. The number taking microcredential programs from edX, the online course provider created by MIT and Harvard and the other major provider of this educational model, rose to 65,000 by the end of April, increasing 14-fold since early March alone.

“People are looking for shorter forms of learning during this time. They don’t know whether they have two months, three months. They’ve lost their jobs,” said Anant Agarwal, CEO of edX, which had the fortuitous timing of launching a new stackable bachelor’s degree in computer science in January and three more in May — in writing, marketing and data science — and trademarked the term “MicroBachelors” to describe them.

“For them the ability to earn a microcredential within a few months and improve their potential to get hired as we come out of Covid becomes much more important,” Agarwal said.

Surveys bear this out. A third of people who have lost their jobs in the pandemic, or worry that they will, say they will need more education to get new ones, the nonprofit Strada Education Network found.

They don’t have time to waste. Among lower-income adults, who have already been disproportionately affected, one in four say they have only enough savings to cover their expenses for three months if they’re laid off or get sick, the Pew Research Center reports.

“They don’t have two to three years of runway to put a pause on their life,” said Scott Pulsipher, president of nonprofit, online Western Governors University, or WGU, which has rolled out microcredential programs in states including Nevada that supply certificates and certifications on the way to degrees in information technology and health care.

“The affordability question is factoring in, too,” said Pulsipher; the cost per credit of WGU’s IT microcredential program comes to about $150 per credit and edX charges $166 per credit for its MicroBachelors degrees, compared to the average $594 it costs to earn a credit at a conventional in-person university.

“No one planned for or designed for a pandemic but it starts to heighten the differentiated value that comes from things like microcredentials,” Pulsipher said.

Agarwal reports edX signed up as many learners in April as it did in all of last year — it now has 30 million — and a survey of new students found that 11 percent were already unemployed or furloughed and trying to learn skills that would help them get new jobs; edX has announced that it will offer a 30 percent discount on MicroBachelors programs to students who have lost their jobs because of the pandemic.

Even before the coronavirus hit, several providers were making a push for microcredentials. WGU and edX teamed up to create the program in which Nelson is enrolled. BYU Pathway Worldwide, an online spinoff of Brigham Young University-Idaho, has created stackable bachelor’s degrees in all of the subjects it offers. It calls them “Certificate First.”

That’s because students in these programs, and the others like it, first get certificates or certifications — short-term or industry-recognized qualifications — on their way to earning associate or bachelor’s degrees toward which the credits also count.

It’s an approach whose advocates say can help not only people who need credentials quickly to reenter the workforce, but solve a lot of problems that have been dragging down the success rates of college students seeking bachelor’s degrees.

“If you were designing [college] from scratch,” said BYU-Pathway Worldwide President Clark Gilbert, “this is how you’d do it.”

More than a quarter of students in conventional college programs quit after their first year, when a degree still seems intimidatingly far off. For many, it is; more than 40 percent of bachelor’s degree candidates still won’t be finished after even six years, according to the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, which tracks this.

“And you wonder why we’re losing those populations in droves,” said Gilbert.

Weighed down by negative news?

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.Earning credentials on the way provides a series of rewards that may make students more likely to persist. Even if they don’t, they’ll have something to fall back on that can help them get, or advance in, a job. Under the existing system, the Clearinghouse reports, 36 million have dropped out with no degrees or certificates to show for their time in college — but often student loan debt to repay.

Agarwal likens getting a bachelor’s degree in this new way to climbing Mount Everest by first hiking to the base camp at about 17,000 feet and getting acclimated to the altitude before attempting to achieve the summit.

Earning that first certificate, Agarwal said, is like reaching the base camp; stacking them into a bachelor’s degree, like getting to the top.

Early returns suggest receiving those rewards along the way is helping the so far limited number of people who have already tried microcredential programs — at edX, for example, they comprise about a tenth of all enrollment — climb more quickly.

Nearly 70 percent of students racking up industry certifications on their way through the edX/Western Governors stackable IT programs finish their bachelor’s degrees not in four or six years, but in two, the university says. That’s in part because they also get 27 credits, on average, for earlier education or life experience, another new way of speeding students through their higher educations that is available from a growing number of colleges and universities.

At BYU-Pathway Worldwide, officials there report, the proportion of students who drop out between their first and second year has fallen more than 20 percentage points, from 35 percent to 14 percent, since the start of the Certificate First program.

“That early milestone — the early win — is so motivating,” Gilbert said. “Now they understand how education works. And if we lose someone, instead of being a dropout, they’ll have a certificate. Is it as good as having a bachelor’s degree? No, it’s not. But is it better than being a dropout? Yes, it is.”

That’s what student Brian Salazar experienced. “It’s very encouraging every time you pass one of the certification tests,” said Salazar, who has already earned certifications in Amazon AWS system operations administration, IT service management, Linux and several other industry cloud and network subjects.

An IT tech in Carson City, Nevada, Salazar had already gone to community college, but “I didn’t really have many job offers after getting my associate degree.” Once he started earning all of those certifications, “I started getting lots of offers,” even without the bachelor’s degree he expects to finish this year.

Certifications and certificates can also show prospective employers precisely which practical skills students have learned, which is increasingly important at a time when only 11 percent of business leaders in a Gallup poll strongly agreed that college graduates had the skills their businesses require. Two-thirds of Americans in a Pew Research Center survey said that students aren’t getting the skills they need for the workplace. Students don’t feel ready either: Only 41 percent say they consider themselves very or extremely prepared for their careers, a McGraw-Hill survey found.

It’s no coincidence that the institutions furthest along with stackable credentials are nonconventional ones. Some traditional universities say they want to add them, too, but longstanding practices are hard to alter.

“Education hasn’t changed in hundreds of years, and whenever someone comes and says, ‘Hey, look, this is something cool,’ they don’t understand it, or they look with suspicion on it,” said Agarwal.

Some other universities are trying to embrace this change. Many have programs that already help students earn industry certifications in fields including accounting and manufacturing. The University System of Georgia in January launched what it calls a “nexus degree” — certifications that add up to associate degrees that can then add up to bachelor’s degrees. The financial and enrollment challenges they now face also are pushing colleges and universities to seek new sources of revenue.

Conventional institutions that are working to come up with stackable credentials, however, have been slowed down by accreditation requirements, occasional faculty resistance, the need for certification bodies and academic departments to collaborate and the difficulty of explaining to consumers how the process works.

There’s growing pressure on all colleges and universities to speed up the process of embedding certifications and certificates into bachelor’s degrees. That’s because, even before the coronavirus created new problems for them, traditional higher education institutions already appeared to be losing business to those quicker, cheaper credentials.

Nearly one in 10 undergraduates today is working solely toward a certificate, and more are pursuing certificates or associate degrees than are studying toward bachelor’s degrees, the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce reports. This is cutting into a market for bachelor’s degrees that’s already suffering from a decline in the number of 18- to 24-year-olds.

Shifting so much attention to vocational skills concerns some higher education experts.

Short-term certificates “can be a positive force in people’s lives,” said Chris Gallagher, vice chancellor for global learning opportunities at Northeastern University and author of College Made Whole: Integrated Learning for a Divided World. But suggesting it’s okay for learners to stop before they reach a bachelor’s degree, Gallagher said — just because they’ve already received some shorter-term credential — leaves them at a comparative disadvantage.

That’s because, while their income potential may be higher than if they quit with nothing, certificate holders who stop short of a bachelor’s degree may miss out on substantially greater earnings; a typical graduate with a bachelor’s degree will earn $1.19 million over his or her lifetime, compared to $855,000 for someone with an associate degree and $580,000 for a high school graduate, the economic think tank The Hamilton Project calculates.

By comparison, workers who finish a certificate make up to a comparatively modest $2,960 a year more, on average, than those with a high school diploma, according to the Community College Research Center at Teachers College, Columbia University. (The Hechinger Report, which produced this story, is an independent unit of Teachers College.)

Lifetime earnings estimates for certificate holders comparable to those for bachelor’s degree recipients are not available. Some research, including from the public policy think tank Third Way, has found much less financial benefit from them. The value of some certificates also fades over time as job demands change. Back at her breakfast in Henderson, Amy Nelson said friends have begun to ask her about the stackable credentials model. Their interest was piqued when she posted on Facebook how many certifications she’d already earned on the way to her degree.

“I had only been doing this for one year and I had all this stuff. It just blew my mind, so I wanted to share that,” she said. “To be the girl who was maybe not going to finish high school and now to have all these degrees, it’s sort of amazing.”