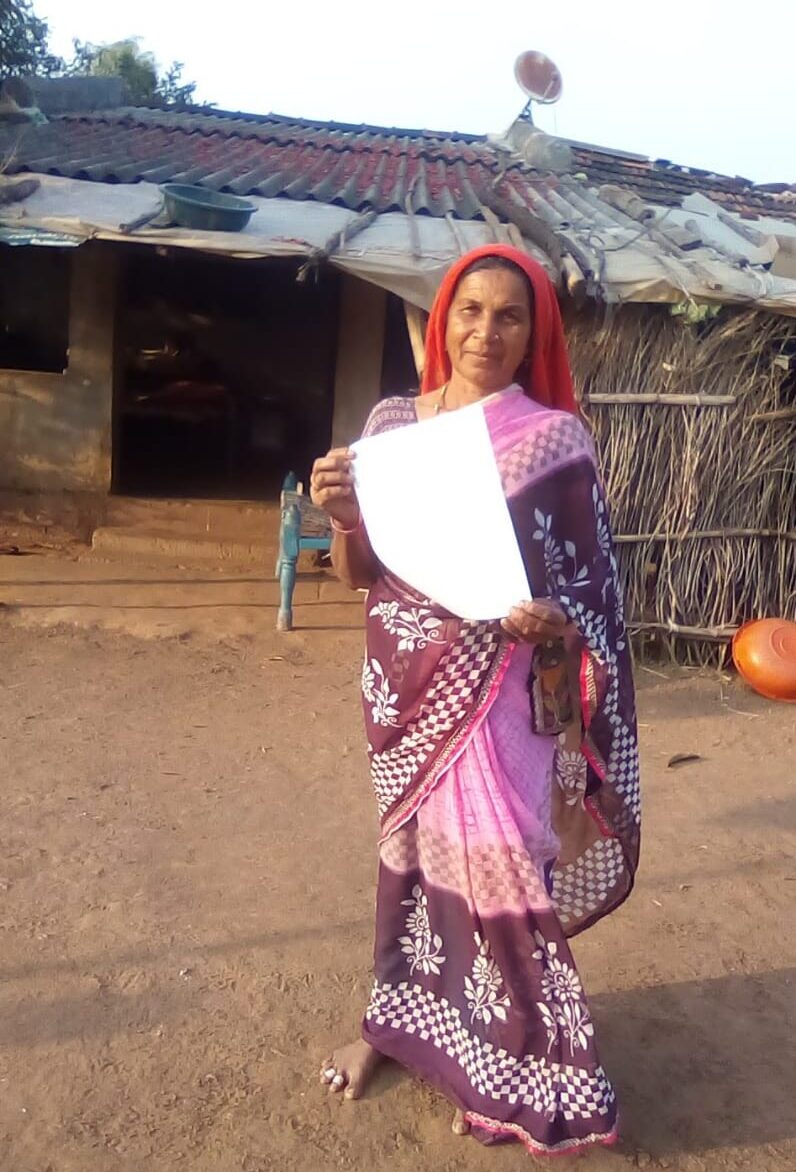

When Bhanuben Bharatsingh’s husband died, his elder brother took control of the field she had tilled all her married life. This was the norm in Gujarat, the state in western India where she lived, but Bhanuben knew that her family’s well-being depended on what she did next. So she went to the village administration office to meet the friendly local paralegal.

“I asked her what I needed to do to assert my right to my husband’s land,” she says. The paralegal advised her on the documents she needed to collect and counseled her to talk to her family. “Today, I own the land I till; I have no problems and no fears. What’s more, I’ve been able to access government schemes to buy a tractor and a pump for irrigation,” she said in a video testimony.

Bharatsingh is one of those rare women who has been able to access her land rights in a staunchly patrilineal state where women cultivate fields, but the majority remain landless. Globally, less than one-fifth of landowners across the world are women, and almost 40 percent of all countries limit women’s property rights in some way. Since 2005, Indian law has recognized that daughters and sons have equal inheritance rights. But while 73 percent of rural women work in the agriculture sector, only about 14 percent own land.

This is problematic. “Women’s access to land and property titles is the single most important contributor to their empowerment,” developmental economist Bina Agarwal says. Her 1994 award-winning book, A Field of One’s Own, traced regional variations in women’s land ownership in five South Asian countries, and highlighted how crucially land tenure impacts women as well as their families. Subsequent research bears this out: Mothers who own property and family assets are more likely to spend on the household. Also, their children are healthier and better educated, when compared to the spending behavior in families where fathers own everything. Agarwal, now a professor at the University of Manchester, spearheaded the successful campaign to amend the Hindu Succession Act in 2005, to give men and women equal inheritance rights over land.

Weighed down by negative news?

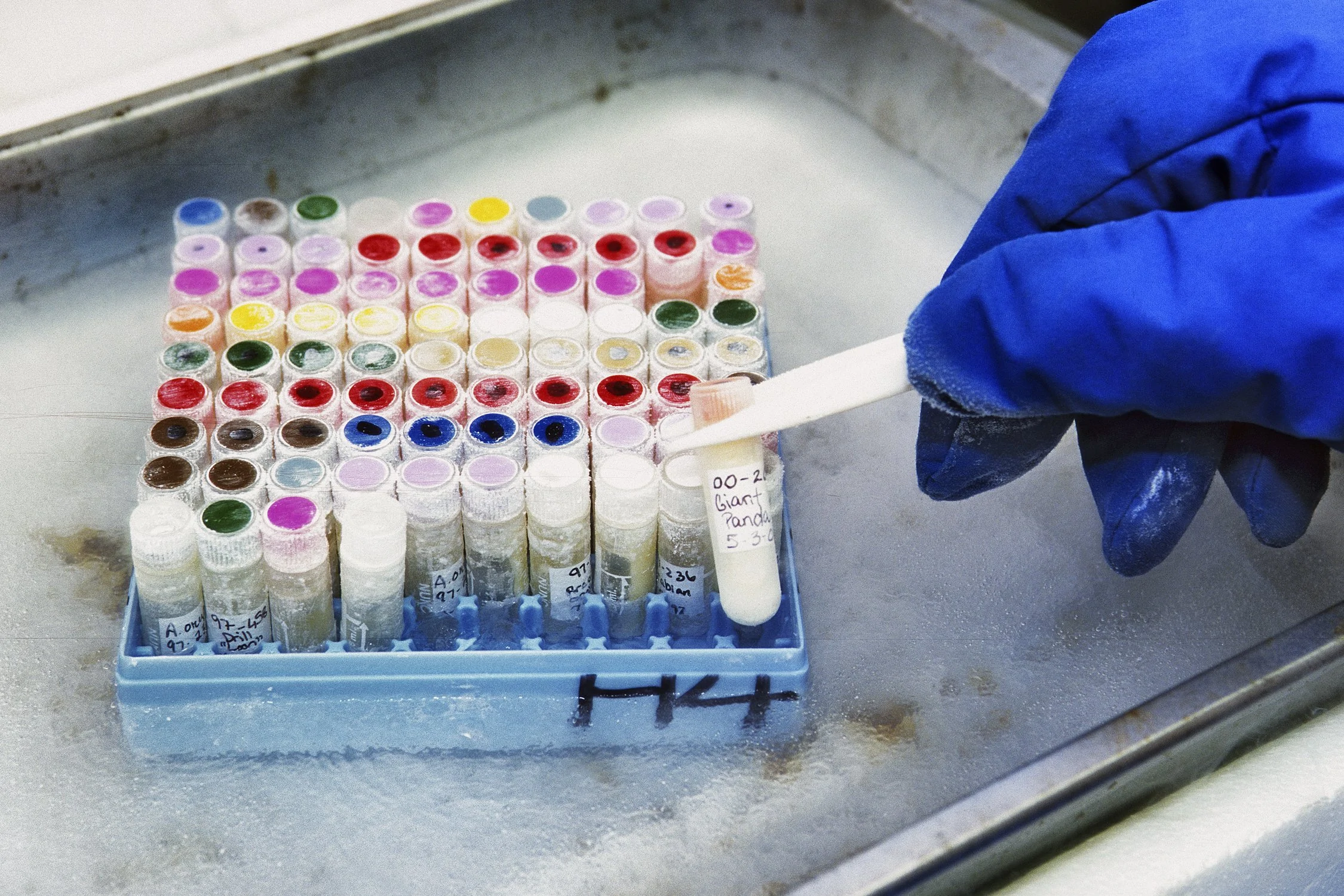

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.“In spite of the favorable law, at least for Hindus, we found that women in rural Gujarat faced significant problems in accessing their land rights,” says Minal P. of the Working Group of Women for Land Ownership (WGWLO). This consortium of 48 grassroots NGOs and individuals came together in 2002 after Agarwal conducted a workshop on land ownership as a livelihood issue for women in Gujarat. WGWLO observed that rural women had limited access to legal aid and that the local administration was not fully sensitized to the 2005 amendment to the Hindu Succession Act. With an agenda to raise awareness about women’s land rights, as well as to make legal aid more accessible, the consortium has trained over 200 paralegals from within local communities to help women like Bharatsingh access their digitized records and fight for their land rights.

My farm, my right

The paralegals are a diverse group aged between 20 and 55; some unlettered, others high school dropouts and then some, like 38-year-old Shardaben from Gujarat’s Navsari district, college graduates.

A paralegal since 2021, Shardaben travels 14 kilometers on her motorcycle twice a week to the Swabhumi Kendra (“land owners’ center” in Hindi) set up by WGWLO. Women from about 80 nearby villages seek legal counseling and help with drafting applications and accessing digital land records here. “By the time I reach, there are always eight or 10 women waiting, sometimes even more,” Shardaben says. “And my phone rings all the time!”

There are similar Swabhumi Kendras in 15 districts of Gujarat. Between 2013 and 2019, a World Bank report estimated that WGWLO had helped 8,818 women (mostly of lower castes and tribes) secure land titles; today Minal estimates they have helped as many as 20,000. Shardaben and other paralegals undergo four training sessions a year, conducted by the lawyers and legal aid organizations among WGWLO’s members, and regularly advocate for their clients with local revenue officials. Armed with this legal training, Shardaben and other paralegals challenge patriarchal mindsets and speak to stakeholders in a language they understand. “Earlier, when I spoke about women’s rights to the community and the mamlatdars [local revenue officers], they didn’t listen to me,” she says. “Over time, they’ve come to respect my work and my voice.”

The work is not easy. Shardaben and other paralegals encounter challenges as they, in turn, challenge patriarchal mindsets. “Families often say that since daughters marry and go to their marital homes, why give them a share of land?” she says. “I ask in return, what when sons migrate for better jobs? But even now, often when I say that the law gives sons and daughters equal rights to family property, they ask where I’ve learned these new-fangled ideas….” Matters often get heated, she says, and families accuse her of trying to fragment their land holdings or cause rifts among them. Regular training helps: Minal, who has been working with WGWLO for over a decade, says that it has helped many paralegals to confidently talk to their community, as well as government officials. Many now draft legal documents, thereby saving lawyer fees.

Being a formal but unregistered consortium of NGOs has pros and cons. On the one hand, grassroots organization members like Maldhari Rural Action Group (MARAG) enable WGWLO to work with otherwise hard-to-reach and historically underserved pastoralist, lower caste and tribal communities. On the other hand, the dispersed nature of the consortium makes it hard for WGWLO to raise funds. “Different donors support our training programs for the paralegal workers and often, partner NGOs pitch in,” Minal says. “But funding remains a challenge.”

“When one woman gets her land rights, others will follow”

It helps that not only does Indian law recognize men and women as having equal inheritance rights, but the government also has several schemes and subsidies specifically for women farmers. Shardaben says some of these — like subsidies on tractors and farm equipment and incentives for forming farmer collectives and market linkages — tend to incentivize men to transfer land titles to women. “We help women access these schemes, and when others see this, they become easier to convince,” she says. “Now even government officials recognize that we’re aiding their own development work.” So much so that today, nine out of 15 Swabhumi Kendras are located within the offices of the local administration.

Anu Verma, the Asia regional coordinator of International Land Coalition, which advocates for land rights for the marginalized in 81 countries, says that these laws have provided crucial support to WGWLO’s mission. Similar efforts elsewhere have not been as successful: “Other countries, especially in Central Asia, are 30 years behind India in this respect, and formal land provisions have proven difficult to enforce there,” she says.

WGWLO is now expanding operations to other Indian states and has developed a certificate course in women’s land rights.

Tackling the base of the iceberg

However, land ownership does not automatically empower women. Minal observes that often, even when women own their farms, men still tend to control big decisions.

“Women’s land rights are just the iceberg’s tip,” Verma says. “For long-term social change, we have to work on the base of the iceberg — patriarchy and the barriers it creates to women’s empowerment.” Tradition continues to overrule law in many cases, and it remains common for women to sign away their share of family property to maintain harmony with their brothers. Also, to be fully effective, equality in land rights needs to be extended across the board, by extending the 1937 Muslim Personal Law to include agricultural land rights for women. The law also needs to better protect village commons and landless farmers’ and pastoralists’ rights to them.

“While WGWLO’s paralegals do an important job at the grassroots [level], a lot more needs to be done at the systemic level to improve women’s land tenure rights,” Agarwal says, arguing for larger-scale, higher-impact solutions such as facilitating women’s farm cooperatives.

On the ground, however, Shardaben and her cohort of intrepid paralegals are slowly making a difference. Minal states that at least 25 percent of the women they work with are making bigger financial decisions, “which would’ve been unheard of a decade ago.” As Shardaben revs her trusty motorbike for yet another day at work, she dreams of becoming a lawyer one day. “If and when I start my own practice, my work on land rights will continue,” she says. “For I’ve seen that when even one woman succeeds, others follow her footsteps….”