Amid late spring blooms and the summer tourist crush, 35-year-old Mohammad Mateen drives across the city of Srinagar to inspect pashmina shawls being woven for his homegrown Kashmiri brand, Blossoms of Heaven. He pulls up in front of master weaver Abdul Hamid’s house, a two-story structure surrounded by fruit trees. Hamid ushers us up the wooden steps to his attic workshop with two looms, and tells a story of revival. “Ten years ago, I used to weave four to five shawls a month,” he says. “Today, by god’s grace, I weave more than 30.”

Here in the Kashmir valley at the Indo-Pakistan border, a region that has been known for violent conflict since the 1990s, Mateen and Hamid represent a brave new generation. Through the practice of traditional crafts, they are trying to rebuild lives and livelihoods, a critical aspect of peace-building and economic redevelopment in former conflict zones. The road to economic rehabilitation has been long and hard.

Like conflict zones across the world, Kashmir had been isolated from the rest of the country, and its fabled artisans, from their markets. “It felt as if while we Kashmiris struggled with turmoil and violence in our backyards since the 1990s all the way up to the early 2000s, the world left us behind and moved on,” Sajid Nazir, senior faculty at Craft Development Institute, Srinagar, remarks. “Our master craftspeople had had no contact with the market for decades, and years of conflict had eroded their confidence and trust. As for the younger generation, they were more interested in migrating to safer, more lucrative cities, than in practicing traditional craft.”

Peace began returning to the valley in the first decade of the millennium, but sporadic violence and internet shutdowns made it hard for local businesses to grow. “I still remember 2019, the last time that Kashmir experienced serious violence, curfews and one of the world’s longest internet shutdowns of over five months,” Mateen says. “I feared for our survival, and that of the craftspeople dependent on us.”

Cut to 2024, when much has changed for Mateen, and other entrepreneurs like him: “We employ, directly and indirectly, over 400 weavers across Kashmir today,” he says. “And we’ve managed to expand to markets in Qatar and other parts of the Middle East.”

This revival of craft-based livelihoods in Kashmir is thanks, at least in part, to a question that Gandhian craft visionary LC Jain posed in the early 2000s: Could incubating craft businesses in Kashmir create more sustainable livelihoods, revive skills that were in imminent danger of extinction and help the region recover from decades of conflict? Jain, who was the first to apply modern marketing techniques to promote handicraft sales in India, and had developed the government-owned Central Cottage Industries Emporium, thought so, and for good reason.

Kashmir has a rich craft tradition, and it is the third-largest livelihood sector after agriculture and tourism. Craft, traditionally practiced in the safety of people’s homes, is relatively safe even in times of conflict. So when Jain died in 2010, his family created a trust to give fruition to his ideas and thus, Commitment to Kashmir (CtoK) was born. The nonprofit was developed by some of India’s foremost craft activists and advocates – Laila Tyabji of Dastkar, Manju Nirula and Gita Ram of the Crafts Council of India, Ritu Sethi of Craft Revival Trust, Gulshan Nanda, former chairperson of Central Cottage Industries Emporium and Rathi Jha, the founder of the National Institute of Fashion Technology.

“The idea was that these craft-based businesses would have a ripple effect,” Shruti Jagota, project director at CtoK says. “They would help revive traditional handicrafts, create much-needed jobs in the craft sector, and perhaps even reverse migration from the state.” The idea began showing results almost instantly.

In collaboration with the state’s apex handicraft and handloom promotion agency, Craft Development Institute, CtoK began mentoring their first cohort of grantees in 2012. “Designers from across the country taught us how to innovate in terms of designs and colors and sales, and marketing experts taught us how to price our products, interact with customers and display our products in exhibitions,” Mateen, part of this first cohort, recalls. “We learned a lot, and above all, became more receptive to new ideas and new ways of doing business in order to stand out in a crowd.”

To date, CtoK has incubated 37 young craftspeople and Jagota estimates that over 85 percent have set up small and large craft enterprises, or are continuing in other capacities as leaders in the craft sector. Through their program, 850 new design and market-driven products have been developed and sold. These include not only crafty papier-mâché Christmas ornaments and contemporary leather accessories, but also products like hand-painted wooden boxes that fuse traditional Kashmiri motifs, like roses and tulips, with the reality of conflict — stones, barbed wires and army uniforms. Many new business ideas have emerged: For example, embroiderer Anjuman Ara is developing high-fashion embroidered garments with a CtoK designer. Shabir Lone is training women impacted by violence in the traditionally male dominated art of kani weaving, in which cane needles threaded with different colors are used to create intricate patterns on the loom.

Their efforts to connect artisans directly with their markets through regular exhibitions and bazaars across India, and now through their online platform Zaina by CtoK, have been a moderate success. Going by their sales records, Jagota reckons that all their grantees have sold at least 60 percent of their stock in offline events. “Also, I think we’ve been quite successful in making them independent of us,” she says.

But focusing so much money and effort on small cohorts has been difficult to explain to donors looking for high impact numbers, especially during the violence and the long internet shutdown of 2019, and then the Covid-19 pandemic. “So we’ve rethought our strategy in the last year,” she says. “We are now exploring the idea of working with craft clusters instead of individual entrepreneurs.”

CtoK is not the first to try the cluster approach. In 2018 to 2019, the World Bank and the Craft Development Institute identified several areas across Kashmir, with concentrations of people practicing crafts like willow basketry, wool weaving and crewel embroidery, in order to train groups of artisans to sustain and market their work.

One of these clusters consisted of about 600 women embroiderers in Noorbagh, a neighborhood in Srinagar. They were trained and connected to markets by artisan-owned crafts company RangSutra. RangSutra conducted interactive workshops to help the embroiderers hone existing skills, develop rigorous quality control and enhance their creativity over one year. The company also gave the collective running orders of embroidered garments to fulfill. In 2023, their collective was incorporated as a “producer-owned company” by the government, called Noorari.

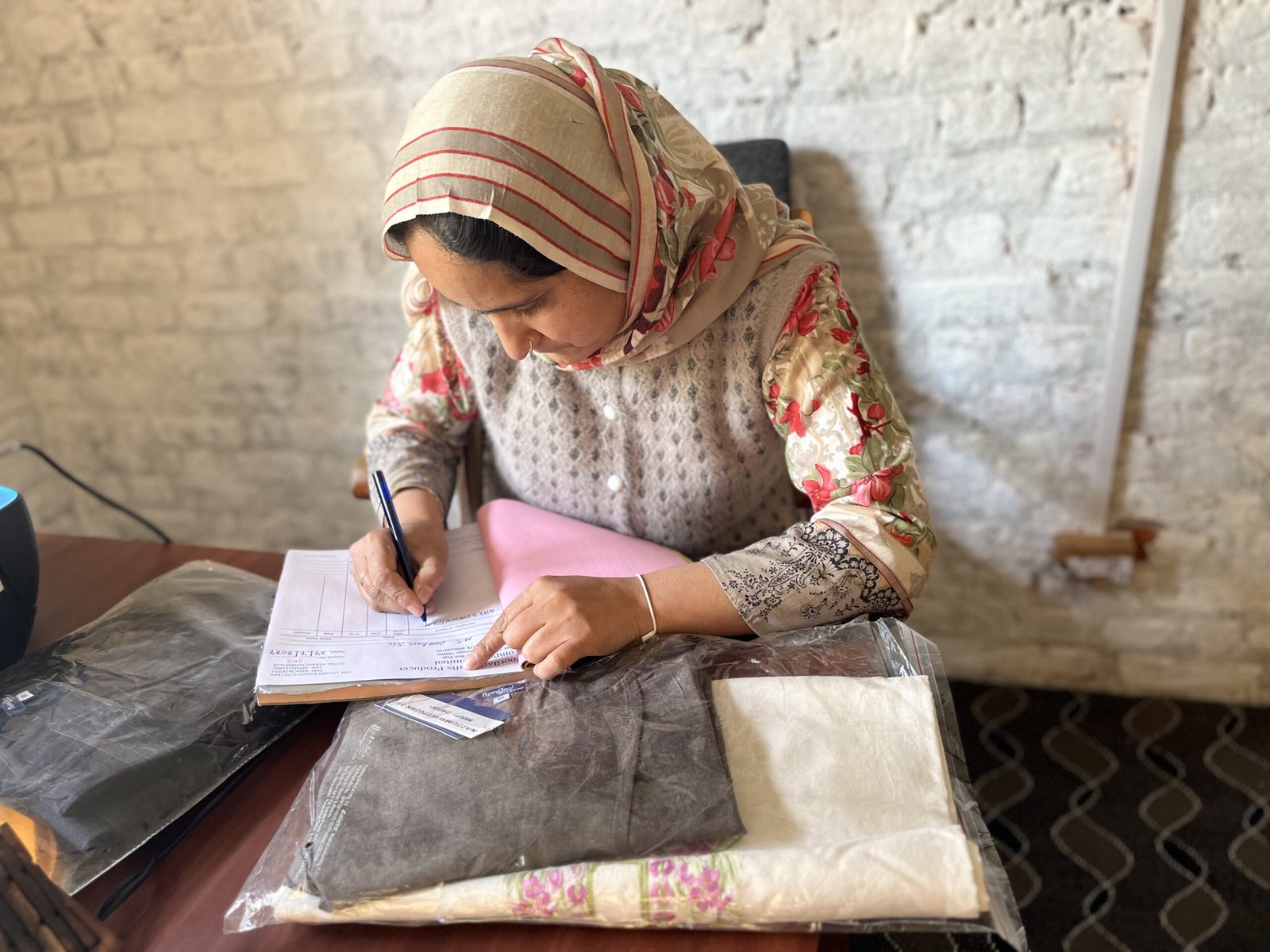

Nazir and I walk through the narrow lanes of Noorbagh to the Noorari office and are met by one of the directors of Noorari: 30-year-old Sahiba, a single mother and the sole wage earner in her family. She estimates that of the original 600 women trained, at least 200 remain active and able to earn about $9 to $12 US per day. In the workshop, about 30 women work on completing an order.

“Working with designers has really refined our sensibilities,” Masrat Jan, a board member who oversees the production, says. “Earlier, we worked on a piece rate basis for traders obsessed with keeping the price low at the cost of craftsmanship. Now we’re rewarded for the fineness of our stitch…”

With their training complete, the ladies of Noorari are working on an independent marketing plan. Sahiba wants to grow their modest Rs 5 lakh (under $6,000 US) profits tenfold in the next five years, but as none of them have experience of using social media marketing techniques and many are still traditionally homebound, this may prove challenging.

“We all really want this to work,” she says. “After the years of uncertainty and conflict, having a business and giving employment to so many other women is an amazing feeling.”

As the sun sets over Dal Lake, Mateen stares at the clouds gathering above. “We’ve grown up with violence around us, we’ve seen months of peace disrupted by a single act of violence,” he reflects. “As a businessman, I wonder: How can we take this peace for granted?” Indeed, across the world’s conflict zones — from which, the UN estimates, over 114 million people have been forced to flee for their lives and livelihoods — the uncertainty of peace makes it difficult to do business. “In 2019, when the violence resulted in a lockdown, our distribution channels were disrupted, we couldn’t even visit the weavers and none of us had any connection with the outside world,” he says. “Our business nearly folded.”

Other aspects of working in Kashmir are equally tricky. Jagota says that in 2019 and 2020, key funding sources dried up. It has taken CtoK two years to find their footing. “Also, our experiences with the grantee program have shown us that one year is too short a time for mentorship. For craft business development in Kashmir, I think one needs at least two years if not more,” she says.

The Noorari cohort’s struggle to stay afloat underlines these challenges. But the pride on their faces as they display their exquisite embroidery is enough to gladden even the most cynical heart. “Noorari has given me a livelihood and dignity, two things I never thought I’d earn through the troubled years,” Jan says as she oversees the tracing of an embroidery pattern. “The best thing is that my two little daughters are so proud of me.”