This story was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education.

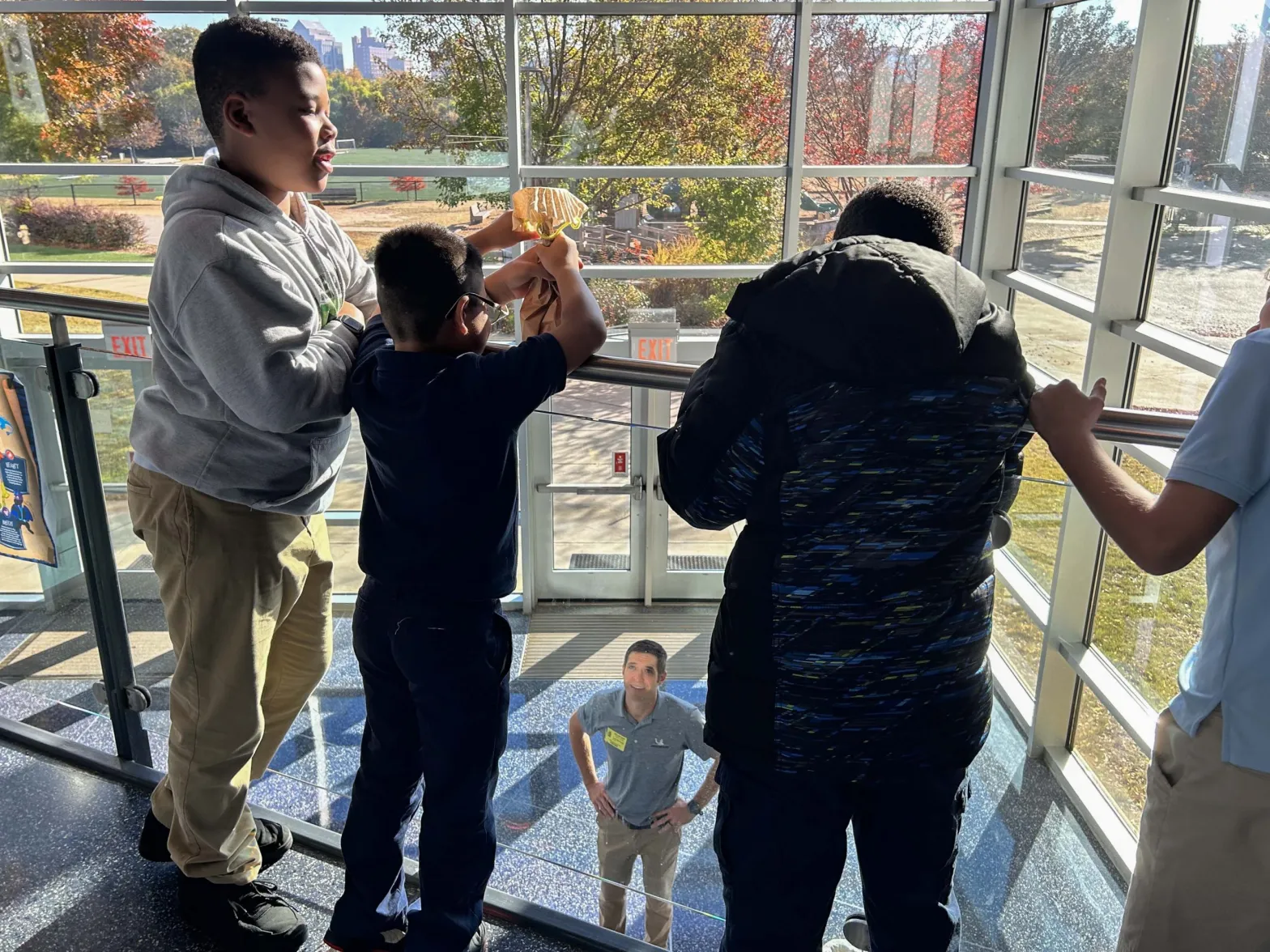

The brown paper bag hit the ground with a smack. A Michelin engineer picked it up off the concrete and opened it, revealing a cracked, leaking egg. The third graders at A.J. Whittenberg Elementary School of Engineering groaned in disappointment when they saw the runny mess. Then, they made way for the next group of students, who were eager to drop their own bag from the staircase in hope of a different result.

A coffee filter parachute was attached to the bag, and inside, an egg sat nestled in cotton balls. The students were anxious to see if the paper contraption they built would blunt, or at least slow, the egg’s fall.

Alas, it didn’t. “Scrambled eggs!” the engineer called out.

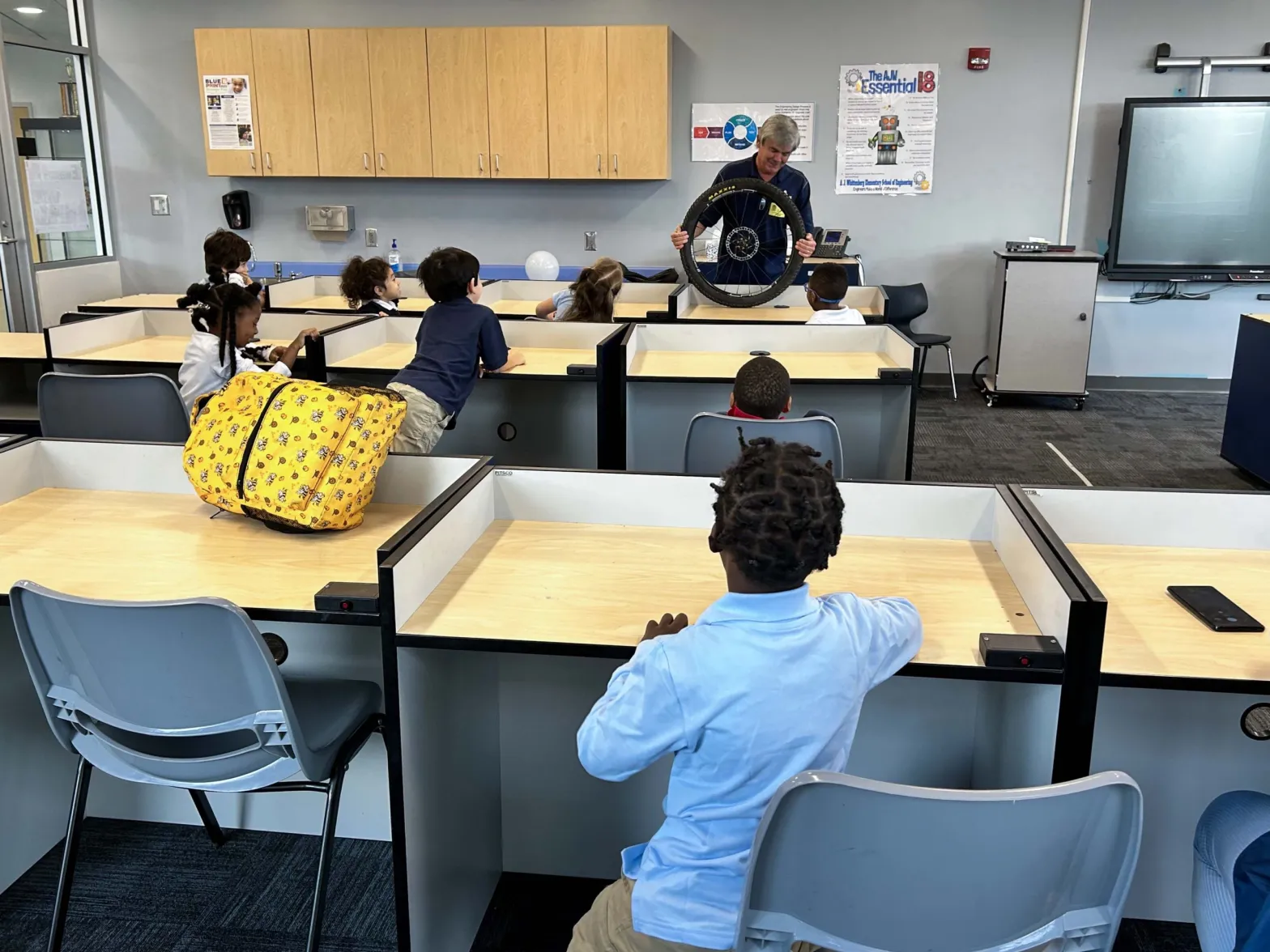

It was engineering week at A.J. Whittenberg, a public elementary school in downtown Greenville, South Carolina, that focuses on science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) in its curriculum. One week per month, engineers from local industries visit the classrooms and talk to students about their careers.

Across the country, schools have shifted toward career-focused education in recent years, reviving a long-running debate on whether the purpose of education is to prepare students for jobs or to be well-rounded citizens.

“We’re not really wanting them to make a decision — ‘I’m in the second grade and now I’m locked in to being whatever when I graduate from high school in 10 years,’” said Burke Royster, superintendent of the Greenville County School District, home to more than 77,000 students, 60 percent of whom live in poverty. “But you want them to have a kind of better, more full understanding of careers.”

A.J. Whittenberg has been around since 2010, when Greenville County Schools opened it as a magnet school in an area that is historically low-income and majority Black. The district decided a focus on engineering at the school would both attract more students from outside its attendance zone and help integrate the school. Its diversity efforts have been successful — the school’s population is 48 percent Black, 32 percent white and 11 percent Hispanic. But in recent years, the school has also become the first step on a longer career runway for young students interested in engineering.

Greenville is now introducing the idea of a career path to students in elementary school and giving students the option to follow those programs to middle and high schools, hoping by eighth grade they will have a better understanding of what they want to do after high school and what it will take to get there. Each elementary school focuses on a specific area — engineering, math and science, the arts, leadership, or foreign languages, among others. The district allows student to attend schools outside of their attendance zones as long as space is available, which means students can opt to continue to follow their chosen career pathway at a middle school with corresponding programs. In high school, students are expected to complete a career cluster by taking several courses in a subject area, such as health sciences, manufacturing, arts or business.

The effort in Greenville is part of a growing national trend in which school districts partner with local industries to develop curriculum and expose students to specialized careers at a young age. These programs serve a dual purpose, district leaders say: Students get career training that could help land them an in-demand job in their hometown, and industries get a pipeline of workers with the qualifications they’re looking for. But some education experts worry the focus on industry qualifications has resulted in schools taking on responsibilities that should fall to businesses, like training workers for specific job duties, to the detriment of a more comprehensive education in schools.

Districts across the country have been ramping up career education programs spurred, in part, by federal legislation updated in 2018 that provides funding for career education (commonly referred to as Perkins V), said Matt Giani, a research associate professor in sociology at the University of Texas at Austin who studies education policy.

In upstate South Carolina, automotive industries have replaced the once thriving textile mills as a dominant force in the region, paving the way for a growing demand for highly skilled workers in engineering and robotics. Greenville County Schools has begun partnering with companies in the area, such as BMW and Michelin, to develop courses in mechatronics and automotive research.

But the approach has taken hold in totally different business landscapes, too.

Since 2017, for example, students in Roscoe, Texas, a rural community of about 1,300 residents, have been able to earn associate degrees and receive college credit by taking career education courses in health care, veterinary services and agriculture through a program called P-TECH. Since livestock is a major part of Roscoe’s economy, the district’s high school even has an embryo lab where students can get experience in high-tech, selective cattle breeding.

“It’s not an education model as much as it’s rural economic and community development — trying to create a highly educated rural population that will lead to the innovation that leads to rural job creation,” said Kim Alexander, former superintendent of Roscoe Independent School District and chief executive of Collegiate Edu-Nation, a nonprofit that builds career education programs for rural schools.

In 2020, policies in 27 states allowed students to earn credentials through career education coursework, such as industry certifications, according to an analysis from the Education Commission of the States.

“We’re seeing this really becoming increasingly popular across states, and it’s fairly recent,” said Giani, the research associate professor at the University of Texas at Austin.

But the increasing focus on industry needs in K-12 has also drawn criticism.

“We need to question the degree to which we should be paying for things that ultimately are going to return value to shareholders rather than return value to the American people,” said Jack Schneider, an associate professor of education at the University of Massachusetts Lowell.

Schneider was one of thousands of people who responded, many of them critically, to a tweet in December from U.S. Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona that stated, “Every student should have access to an education that aligns with industry demands and evolves to meet the demands of tomorrow’s global workforce.” (The Education Department did not respond to a request for comment about Cardona’s tweet.)

For the past several decades, education policy rhetoric has suggested that the purpose of education is to prepare people for work and strengthen the economy, Schneider said, but schools are also a place where students should experience art, music and literature and think creatively.

“For me, it’s about recognizing both of those things at the same time, and figuring out how then can we support a vision of public education that has room for both of those truths,” Schneider said.

Weighed down by negative news?

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.In a study published this fall, Giani found that some industry certifications, such as cosmetology and health sciences, were associated with significant boosts in earnings and employment in those fields, while others had little to no change in outcomes for students.

And even though the industry certifications were associated with higher earnings for students who did not attend college, wages earned by those students immediately after high school were still generally at or below poverty level.

“Overall, yes, certifications are good. But not if we’re using them as the sole or primary indicator of students’ career readiness,” Giani said.

Instead, industry certifications should be one piece of a larger program that includes college credit and work experience, said Joel Vargas, vice president of programs at Jobs for the Future, a national nonprofit focused on workforce education and policy.

But Vargas said schools are still trying to overcome a belief held by many parents, and even educators, that students in career education will immediately start working after high school instead of enrolling in college or additional training.

“The jobs today require such a high level of skill — and increasingly will in the future of work — that a lot of the kinds of skills that you need you also can make an argument that those are the skills you need in college as well,” Vargas said. “And yet, we have this kind of false segregation of well, that pathway is for kids going to college, and that one is for kids who are just going to start to work.”

In 2017, Greenville County Schools awarded 601 industry certifications to students. By 2022, that number grew to 8,745.

Next fall, the school district will open a $12.7 million CTE Innovation Center, where high school students can attend specialized career education courses and earn industry certifications in programs such as aerospace, clean energy technology or automotive research. Those programs will change based on demand, said program director Katie Porter; the more popular offerings are likely to get rolled out to the district’s traditional career centers.

The idea of connecting students in Greenville schools to career paths started with magnet schools like A.J. Whittenberg.

A decade ago, students who attended magnet schools with a focus on engineering, arts or foreign languages did not have a clear path to continue the programs in middle or high school, said Royster, the superintendent.

Now, most of the district’s schools have a focus: Students can go from A.J. Whittenberg to Dr. Phinnize J. Fisher Middle School, for example, to continue in an engineering and STEM curriculum, or they can attend League Academy for a middle school more focused on arts. Each high school has specialties as well: Fountain Inn High School, which opened in 2021, was built with manufacturing and STEM in mind.

These programs still offer all the traditional classes of a typical school. Royster counts the elementary school program a success even if students finish fifth grade realizing that engineering is not their field — they are still one step closer to figuring out what they do want.

“At the elementary level, it’s important Whittenberg’s theme towards engineering doesn’t become so focused on engineering that students aren’t well prepared to go another direction or to consider other directions,” Royster said.

In the past, career days for young students often focused on high-interest jobs children already knew about — doctors, lawyers, firefighters, Royster said. The goal now is to also show young students jobs they’ve never heard of.

Career exposure can have a big impact on young kids, particularly those who aren’t introduced to various careers in their own families, according to Vargas, of Jobs for the Future.

“The point is to get them to try it on through experience,” he said.

For Olivia Spencer, attending A.J. Whittenberg Elementary allowed her to realize early on that she wanted to be an engineer. In sixth grade, she enrolled at Fisher Middle School to continue robotics and STEM programs. In high school, Spencer took mechatronics classes at one of the district’s career centers, which landed her an apprenticeship with Michelin. Now, she’s a freshman studying civil engineering at Clemson University.

“I don’t know if I would have necessarily focused in on engineering as much as I did, especially from such a young age,” Spencer said. “I probably wouldn’t have jumped into robotics so early or anything like that, and that’s kind of what put me on the path to today.”

Spencer said the exposure to STEM programs at a young age helped her break into a field that is dominated by men.

“A lot of these interests are developed from a young age, and stereotypically, as a society, we push guys more into that at a young age,” Spencer said. “Once you hit that middle school age especially, it’s hard to start developing those interests. So, I’m hoping there will be more things like A.J. schools or programs that get girls into it early on so more people can realize they have an interest.”

Developing career interests was the focus one day last November, as thousands of seventh graders weaved through a maze of tables and displays set up by hundreds of local industries at the Greenville Convention Center. Students intubated dummies at a station run by a local hospital, while others hammered nails into a log at a station for a construction company.

The school district hosts this seventh-grade career fair every fall. In just one year, the students will be in eighth grade, when they will meet with a guidance counselor to start making decisions about what they want to do when they graduate and which high school classes will get them there.

Justin Mullis, a skills development manager at local Sage Automotive Interiors, handed out wireless phone charging pads while talking to students about the kinds of jobs Sage offers.

Sage has only partnered with the district for a year, but the company has already started attracting some interest from students currently in career programs. Two of the district’s recent graduates started working there while they were in high school last year. When they graduated in 2022, they kept working at Sage while attending Greenville Technical College.

The workforce shortage companies experienced at the height of the pandemic has made partnerships like Greenville’s more attractive, Mullis said. “It’s a dividend that’s paid in a small amount so far with the people we have, but I feel like the work we’re doing now we’ll see three to five years from now,” he said.

A spokesperson for Greenville County Schools said the district, like most school districts, doesn’t track students’ careers after graduation, given the difficulties and costs involved. Administrators do not know if their investment in career education will lead to more students getting higher paying jobs, but they hope it will result in more students walking across the graduation stage with plans for a career in mind.

One thing is clear to Royster: A high school diploma is not enough.

“When you leave us, you need to either be already down your road to college, if that’s what you’re going to do, or we need to give you something that allows you to get to work and earn a living,” Royster said. “And just getting out with a high school diploma doesn’t do that.”