David Benjamin’s recipe for construction materials sounds like witchcraft: Mix corn stalks with hemp and mushroom roots, pour the mixture into molds that resemble the shapes you need, and voilà, the building material will grow all by itself. In five days!

Simply put, this is the process of mycotecture, architecture with mushrooms.

Fungi and facades are unlikely friends architects usually prefer not to mention in the same breath. But Benjamin named his New York architecture firm The Living because he wants exactly that: to bring architecture alive, literally. “Biological systems are adaptable; they live, breathe and regenerate themselves,” he says in his office in the Brooklyn Navy Yard. “Imagine buildings had these traits! This would change our way of life radically.”

Maybe even more importantly, organic materials do not create trash. “Forty percent of the trash in our landfills is from construction,” notes Benjamin, who is also director at Autodesk Research and an architecture professor at Columbia. “We architects like to build for eternity, with steel and cement, but not all buildings need to last forever, and when we look at the landfills, we realize: Maybe we better look for materials which don’t sit in landfills for centuries and millennia.”

He integrates living organisms into his designs to create dynamic buildings that interact with their environment and leave a small CO2 footprint. His first foray into fungitecture together with the New York company Ecovative consisted of three towers, 13 meters high, that served as an event space at MOMA in 2014 and were entirely built from mycelium and hemp bricks. After three months, the towers were deconstructed and composted. In 2021, Benjamin built an arc for the Centre Pompidou in Paris for which he let mushrooms grow on hemp until the structure naturally fused together. Fuzzy cardboard-like clumps the size of ping-pong balls grown from hemp-fungi in his office are the last reminder of the perishable structure.

Admittedly, these projects served primarily to show the world that building with fungi was doable — the prototypes weren’t exactly move-in ready. This year, however, Benjamin will test the concept for the first time on a large scale and build a 300-unit affordable housing complex in Oakland, California. In partnership with Autodesk, Ecovative, the prefab company Factory OS, and the composite façade specialists at Kreysler and Associates, he wants to tackle one of the most urgent problems in the US: the housing crisis.

Kreysler specializes in prefab composite materials, such as fiber-reinforced polymers (FRP). The company claims that its lightweight FRP façade of the San Francisco MOMA saved 15 tons of steel. “The material has a lot of advantages: it’s long-lasting, durable, lightweight,” Benjamin says about FRP. “It is the same material used in wind turbine blades. But it has one big disadvantage: It’s carbon-intensive.”

The solution: A “mushroom sandwich.” On his screen, Benjamin pulls up the colorful renderings of the Oakland project: Between the fiberglass shell and the interior walls, filler grown from mushrooms and hemp will serve both as natural insulation and carbon storage. “We’re trying to combine the high-performance qualities of the fiberglass composite with a carbon-sequestering mycelium core,” Benjamin says. “Together, the combination results in a net zero or even carbon-negative footprint.” The carbon-intensive fiberglass could be as thin as three millimeters, and the four to six inches of mushroom filling would compensate for the resource-intensive production of the façade.

Weighed down by negative news?

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.Also, conventional insulation often contains toxic chemicals. “Typically, a lot of plastic petroleum-based foam would be used for insulation,” Benjamin says. In Oakland, the first three 12-unit houses that will start to be constructed in April will serve as test cases. One will have conventional insulation. The second will have insulation made from hemp and resin. The third will have mycelium-hemp insulation. “Like a petri dish experiment at the scale of buildings, we will compare the energy consumption, acoustics and livability of the three different scenarios,” Benjamin says. The goal: To streamline the production of affordable housing units in a way that is sustainable, fast and cost-effective.

Other materials might be just as sustainable as the mycelium mix — for instance, certain kinds of wood such as balsa. According to Benjamin, however, balsa does not meet the California fireproof standards, but mycelium does. “Also, there might not be enough wood to do everything we need in construction,” Benjamin says. “So we take some existing systems that have a lot of benefits but are not so sustainable and inject some sustainability into them to increase our palette of options as designers.”

To demonstrate how he balances the various challenges, his team at Autodesk created open-source software that tracks various aspects of a design project, such as cost, livability, carbon footprint and sustainability. By moving parameters for the Oakland project on the screen, it becomes apparent which building materials and construction methods might be cheaper but more carbon-intensive, or vice versa. “There are a lot of carbon calculators out there, which is great,” Benjamin acknowledges. “More and more people want to do the right thing. But what we’re addressing with this software is the right framework to make tradeoffs between your carbon goals and other priorities like cost, schedule and habitability. You want a good unit to live in.”

With a combination of pre-fab housing, high-performance facades and sustainable insulation, Benjamin hopes to unlock subsidies that the Biden administration has promised for sustainable affordable housing. If he and his partners prove they are able to build entire complexes in under a year, the California Homekey initiative could provide additional financing for solving California’s housing crisis.

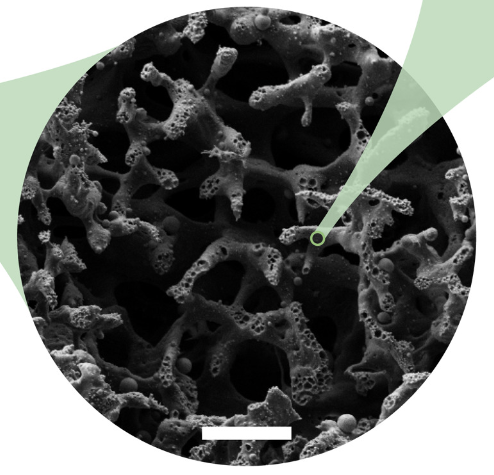

Mushrooms meet a lot of the criteria for sustainable, comfortable living. Benjamin’s construction partner, Ecovative, operates the largest production plant for mycelium materials in the world at its base of operations in Green Island, New York, and has already been producing sustainable packaging from grain stalks and mycelium for companies like Dell and Puma. The white mycelium acts as a natural glue and grows until all the space in the molds has been filled. After drying the product, the result is stable, compact and resilient. “The material is fire-resistant, compostable and uses almost no energy in its production,” Ecovative co-founder Eben Bayer says. “Our goal is to replace plastic and insulation foam in all industries. Mushrooms are nature’s plastic.”

Fungi can also replace the styrofoam in coffee cups. “Styrofoam is toxic,” Bayer says. “After one cup of coffee, we throw the cup in the trash, but it stays on the planet for thousands of years. The recycling system of nature, however, is flawless.” Ecovative co-founder Gavin McIntyre seconds. “We only have one planet, and if we want to have a future, we need to use materials that can be recycled or upcycled.” Even the US military has turned to Ecovative with a $9.1 million defense research contract: When a soldier gets wounded in the field, first aid medics could grow a protective structure from mycelium where needed. And NASA is seriously contemplating mycelium structures on Mars.

“The method generates no trash and is 100 percent organic,” says Benjamin, who has pursued other elements of living architecture. For instance, he recently created a façade from sandblasted Douglas fir for a gallery in New York. Instead of mounting a slick front, he sandblasted the wood to create meandering furrows “as a way to harness the microbiome,” Benjamin explains while showing off small pieces of the treated wood that looks like a furrowed landscape. “When a biologist tested the microbiome after construction, the storefront near Chinatown showed a lot of microbes associated with rice. In a different facade installed in the Brooklyn Navy Yard, we find a lot of microbes that are known for breaking down heavy metals.” What interests Benjamin is “that you can use DNA sequencing as a kind of sensor to learn about these invisible things in the environment.”

His unconventional ideas might stem from Benjamin’s background in art. He studied philosophy and history, and played in an indie-rock band before working in various tech startups and turning to architecture. But what keeps him up at night is the size of the problem he’s trying to solve. “What I’m thinking about a lot is the pure amount of construction that’s going to happen in the near future,” Benjamin says with a sigh. “Experts predict that the amount of built environment we have now will double in the next 30 years. This translates to 13,000 buildings going up every day for 30 years.” One reason why he’s turning to affordable housing is the impact sustainable construction would have there. And still, he says, “what we’ve been doing is insufficient, it’s too incremental. We need bigger levers.”

Whenever he can, he takes a page from nature’s playbook. For jet maker Airbus he mimicked the structure of slime mold, single-cell organisms that can form giant constructs. With 3D printers, he designed the lightest and largest bionic airplane partition ever designed for a plane. It’s currently in the last review stages and will be implemented in the next generation of A320 Airbuses. According to Benjamin, “it reduces the weight by 45 percent, so it will save a million tons of carbon per year.” (Lighter airplanes burn less fuel.)

For his most recent contribution to the Venice Architecture Biennale in 2021, he tried to create the opposite of a “sick” building by designing “Alive: A New Spatial Contract for Multi-Species Architecture,” an immersive installation made from the vine vegetable loofah that asks: “What if we could change our architectural environments to be better hosts for a diversity of microbes and to decrease the amount of harmful ones?” For a previous Biennale, he had planted live mussels in the Venice canals. The speed of their opening and closing, translated into colorful light, indicated to every passerby the health of the water.

Alive from The Living

The most vivid example of his living architecture is probably the glass wall he built for the Art Institute in Chicago: since most windows contain air space, he simply enlarged them until they were big enough to serve as terrariums for live frogs, algae and snails. “A mini-version of the natural ecosystem.” The purpose beyond the beauty: “Frogs swim up to breathe more often when the oxygen in the room is lower. They are natural sensors for the oxygen in the building.”

Benjamin loves the unpredictable nature of his creations. “Design with organic growth means that we are not in complete control of the process. When we architects can make friends with this idea, we might build better structures.”