This story first appeared at The 74, a nonprofit news site covering education. Sign up for free newsletters from The 74 to get more like this in your inbox.

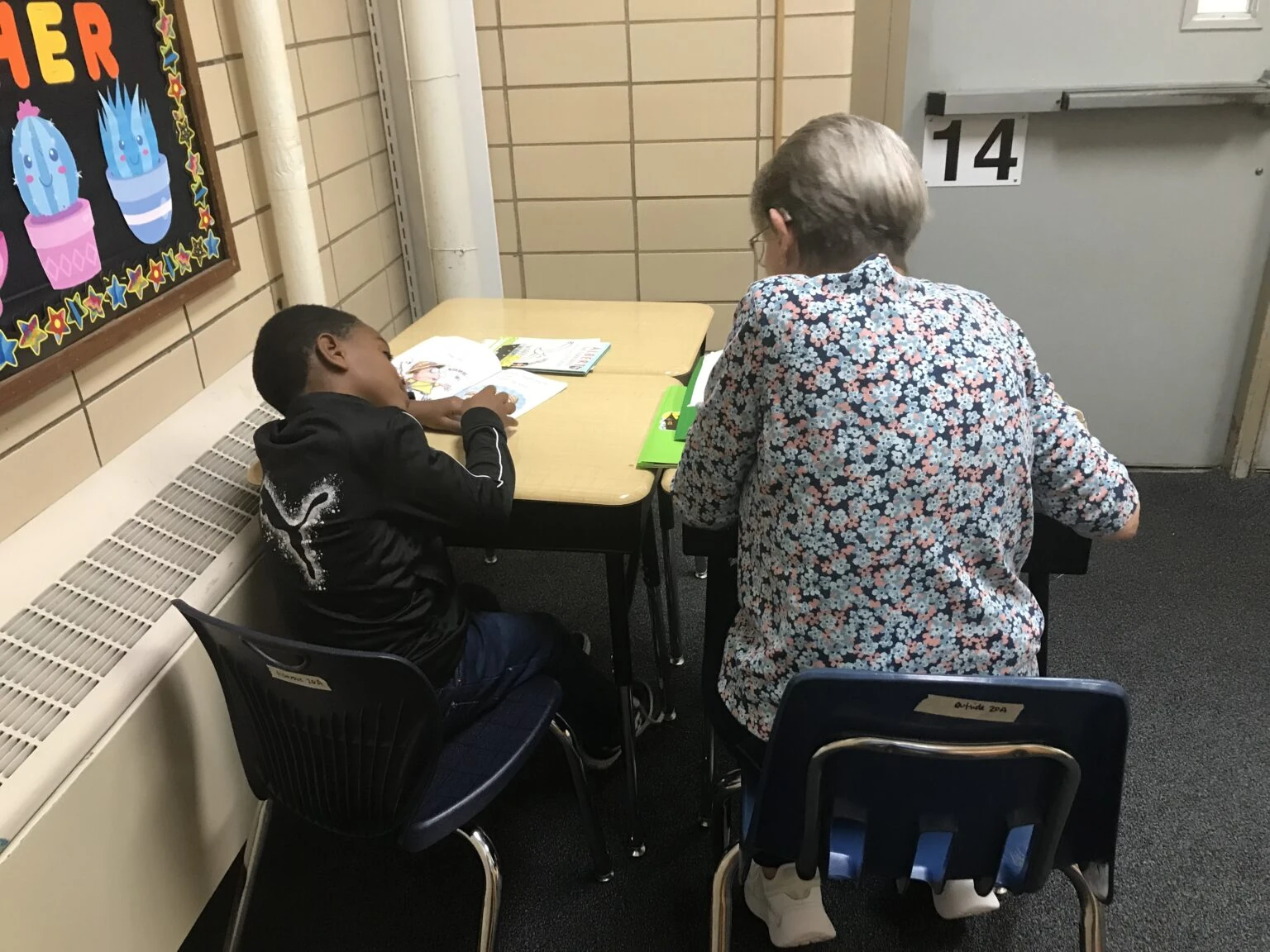

At a desk wedged between a hallway vent and a classroom door, Marge Mangelsdorf coaxed Harlan to write down what he remembered.

The two had just finished reading Hi! Fly Guy, a popular children’s book about a boy and his pet bug. Now it was time for Harlan, a first grader at Bayless Elementary School in St. Louis County, to review the plot and characters with his tutor. But while his vocabulary was improving, he appeared hesitant about speaking and writing prompts like these.

“In the beginning, there was a fly,” said Marge. Clad in white sneakers and a floral print shirt on a sunny November morning, she gave off the air of a gentle but insistent grandparent. “And then he was caught, where — in a jar? And then what happened?”

For a moment, Harlan grimaced. Then, gripping a pen topped with an electric light, he began writing in an unsteady script.

Mangelsdorf spends several days each week in empty classrooms and corridors like these, working with kids through Oasis Intergenerational Tutoring. The program, which pairs volunteers with students for 30–45 minutes each week, is overseen by the Oasis Institute, a St. Louis-based nonprofit that promotes healthy aging through a mix of community involvement and continuing education. According to the Institute’s leadership, intergenerational tutoring has spread to 15 states, though its greatest concentration is in Missouri, where it began 35 years ago.

Participating students between kindergarten and the third grade are identified by their teachers as needing academic or social-emotional support. And while some skew younger, the average volunteer is around 72 years old, with many resembling Mangelsdorf, a mother of three grown children who has lived in nearby Affton for her entire life. After 22 years tutoring in Bayless Elementary and other schools, Oasis has become her later-life mission.

It’s a form of service that addresses critical needs arising from the educational catastrophe of Covid-19. Harlan and his classmates were toddlers when schools began to close in March 2020. Nearly four years later, standardized testing results indicate that elementary schoolers around the country lost the equivalent of years of learning, with students in the St. Louis area still reading and doing math at a lower level than they did before the pandemic. Driven by desperation, and financed by millions of dollars in federal funds, states and districts have built up their own tutoring efforts or contracted with existing ones.

Weighed down by negative news?

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.Oasis’s model holds a unique appeal. Its workforce of largely retired volunteers cost districts a comparative pittance in fees, making their continuing presence sustainable even after Covid recovery grants expire this year. What’s more, their time in schools yields a secondary benefit to the tutors themselves, who remain engaged in the wider world rather than receding into inactivity. Some spend over a decade in the program, building friendships with school staff and their fellow tutors, said Paul Weiss, Oasis’s president.

“The theme is: How do we connect older adults with each other, ideas, and activities in ways that increase the footprint of their lives?” said Weiss. “And how do we position older adults to be more than a population that’s served, but to be a population that is a vital part of American life?”

For her part, Mangelsdorf said she appreciates the opportunity to watch local kids grow throughout the school year. At the end of her session with Harlan, she announced that she would ask that his teacher bump up the difficulty level of his reading materials. Reaching into her bag, she produced a handful of seasonal stickers — accumulated over the years along with an array of children’s books that she awards as prizes — and let him choose between pumpkins and Pilgrims.

“You really did pretty good, okay? And you tried.”

A nationwide experiment

Mangelsdorf, and thousands like her, are participating in a kind of nationwide experiment in high-dosage tutoring, which has raised the hopes of both families and policymakers over the last few years of hampered learning.

The excitement emerged from a remarkable empirical consensus, which shows one-on-one and small-group tutoring to be among the most effective educational reforms that schools can use to lift student achievement. A 2020 research review, gathering the results of 96 randomized controlled trials, showcased the wide scope of tutoring offerings that deliver significant learning advantages, including both reading- and math-focused programs that employed either professional educators or community volunteers.

Advocates quickly embraced tutoring as a solution to students’ clear backsliding during the transition to virtual learning. But questions remained about whether the approach could be successfully scaled up.

To reach the tens of millions of kids who fell behind during COVID, districts needed to recruit an army of educators at a moment when most adults were still concerned about the danger of stepping into schools. Teachers and paraprofessionals, generally found to be the most effective tutors, were experiencing historic levels of burnout, while both private- and public-sector employers struggled to fill openings.

States did what they could to fill the gap, with one analysis of pandemic spending plans showing that districts planned to commit $3 billion to tutoring initiatives. With nearly $200 billion in federal ESSER money expiring next year, however, schools are already feeling a pinch in core academic programs, let alone supplemental offerings.

Access to Oasis tutors costs districts and schools a nominal fee, which Weiss estimates supports roughly six percent of the program’s total price tag. Offerings include reading material and workbooks, summer training for tutors, further coaching during the school year and sometimes help with building program-specific libraries. In cases where those costs are prohibitive, the program sometimes offers discounts. And the Oasis Institute, which operates physical locations in eight hub cities, has recently introduced tutoring programs in southeast Alabama, upstate New York, and the San Antonio area.

Tutors don’t typically bring prior instructional experience to their work (though most are former parents, and many volunteer in a variety of school settings outside of Oasis), but their involvement generally adheres to the guidelines for successful tutoring programs laid out in prior research: It is principally geared toward honing elementary reading skills, conducted at regular intervals and delivered during the school day.

Though Oasis hasn’t yet undergone a rigorous study, the terms of one of its federal grants require the organization to provide proof of its effectiveness. In a sample of 300 students, 97 percent of students working with an Oasis tutor showed improvement in reading performance on a range of standardized exams. In a 2023 survey of educators in schools where Oasis works, 80 percent of classroom teachers said they’d seen improvement in their students’ reading skills, and 67 percent said they’d perceived an improvement in those students’ attitudes at school. Virtually every administrator polled said they would continue to welcome Oasis tutors in their schools.

Jason Sefrit is one of the program’s loudest advocates. The district superintendent in the city of St. Charles — a northwestern suburb of St. Louis, and one of Missouri’s largest cities — said the assistance offered through Oasis provided a sorely needed asset as his schools worked to bring children back to pre-pandemic levels of achievement. In his daily visits to district campuses, Sefrit said, he often walks past half a dozen Oasis tutors huddling with pupils in the halls.

“It’s not a want, it’s a necessity,” he remarked. “These kids rely on their tutors each week to support them.”

That support goes beyond schoolwork. Though tutors are typically assigned to different students each year, they often cultivate deep ties with children by learning their interests and listening to their stories. Some students come from unstable families, while others are simply grateful to have a regular, unfiltered interaction with an adult who isn’t a teacher or family member.

Stacy Butz said that academic gains are cemented by familiarity and mutual trust between adults and students. A reading specialist who has spent 28 years in schools, she also coordinates Oasis’s tutoring efforts at her St. Louis County school district of Ladue. Even before taking on that role, she was impressed by how close students grew to their tutors.

“In a half-hour, they’re able to make gains in reading, writing, and communication skills and develop this beautiful relationship along the way,” said Butz. “A lot of surrogate grandparents are developed because of the connections that are made.”

Over nearly a quarter-century working as a tutor, Mangelsdorf said her students confided so much to her about their home lives and families that she sometimes feels “like a confessor.” The intimacy she forms with kids like Harlan doesn’t just provide immense personal satisfaction. It’s a necessary component to helping them advance.

The fulfillment she gets from that challenge is distinct from what she experienced in her days as a small business owner — or even from her work as an advocate for disabled adults, which she began after raising a child with special needs. One of her daughters, a teacher, also spends her life helping kids; but the interpersonal effects of one-on-one tutoring differ even from those of classroom instruction.

“It’s got to come from within the tutor, and it’s got to draw out of the kid what they need,” she reflected. “I know a lot comes from the teachers, so I’m not taking anything away from any teacher. But maybe my little bit of input pushes a student past where they already were.”

‘Older adults don’t get looked at’

Whatever the effects of tutoring on young kids, Oasis’s work is also meant to help their volunteers.

Gerontologists have long observed the dangerous tendency of seniors to become disconnected from the world outside their homes. The loss of job and social responsibilities, as well as declining physical mobility, has been linked in research studies to higher levels of mortality and severe health problems, including dementia.

More than one-quarter of American seniors live by themselves — far more than similarly aged people in other countries, and more than the combined numbers of those living with their adult children or extended relatives. In a poll conducted earlier this year by the University of Michigan, one in three Americans between the ages of 50 and 80 said they only infrequently had contact with family, friends or neighbors, a significant jump from 2018.

Weiss said that pervasive isolation was what motivated Oasis Institute founder Marylen Mann to look for more opportunities for older adults to contribute. In visits to senior living facilities in the early 1980s, he said, Mann saw residents’ basic needs being attended to, but lamented that their wisdom and life experience were being allowed to wither.

“One of the things that’s hardest is that older adults don’t get looked at,” Weiss said. “They don’t get touched, they don’t get engaged with.”

But when given the chance to be active and help others, seniors’ quality of life can dramatically improve. A 2020 Harvard University study found that adults over 50 who volunteered at least two hours per week were less likely to express loneliness, depression and hopelessness and more likely to be optimistic and purposeful. Putting them in direct contact with school-aged children might be the best way to leverage their talents, especially given America’s growing number of seniors; by the 2030s, the US Census estimates, people over the age of 65 will outnumber those under 18.

Butz said that the benefits of tutoring could be measured in the ties strengthened between local community members. Volunteers often encounter their pupils around their neighborhoods and attend milestone events like elementary school graduations.

Asked to name memorable tutors from her years of working alongside them, she recited a litany of Silent Generation names: Thelma, who stayed with Oasis until she turned 90; Bernard, who spread a love of chess through his students to the rest of their elementary school; Ray, who taught his student to ride a bike in the school parking lot.

“They are taxpayers, and the more opportunities they have to come into our buildings and volunteer their time, the better,” Butz said. “Many of our tutors are previous parents as well — their kids went to our elementary schools, and now they’re giving back.”

‘More positive than playing checkers’

Nick Hall has tutored for nearly a decade in the Ferguson-Florissant School District, where he, his father, children and grandchildren all attended. The former sales executive was initially hesitant to be paired with young children, but his reservations evaporated upon contact with his first student: Kanye, a first-grader who was capable of excelling academically but struggled at times with classroom behavior.

The two forged a bond, in part because Hall himself dealt with disciplinary problems in school. “There are teachers all over the St. Louis area spinning in their graves about the idea of me having anything to do with kids learning anything,” he said.

As he moved through the rest of his elementary years, Kanye would bump into Hall around his elementary school, stopping to crack jokes or occasionally play basketball. Courtside banter sometimes turned to friendly advice on how to stay out of trouble.

Hall kept up his school visits, but the two lost touch as Kanye advanced through middle and high school. Hall said he asked after his former pupil, hoping for good news about his academic and social progress. But the pandemic made it impossible to connect.

This fall, after working with district officials to arrange a visit during the school day, Hall surprised Kanye in the middle of a class period. He hardly recognized the high school junior, who has sprung up well over six feet. Now Hall hopes they can occasionally meet for lunch as the transition from K–12 approaches.

Not every tutor-pupil pairing sparks the same magic, he acknowledged, and a disappointing experience of online tutoring during the pandemic was much less productive than face-to-face interactions. But Hall said he’ll keep working in schools for at least a few more years, perhaps until he reaches the 12-year mark. He likes the symmetry of the dozen years he spent as a student in Ferguson and a subsequent dozen spent working with students.

“It gives people like me — who are looking for something to do that’s more positive than just playing checkers in the afternoon at the senior center — something to do and a place to do it,” he concluded. “It gives you more than a little bit of satisfaction about how you spent your afternoon when you get done with one of these sessions.”

This story was produced by The 74, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on education in America.