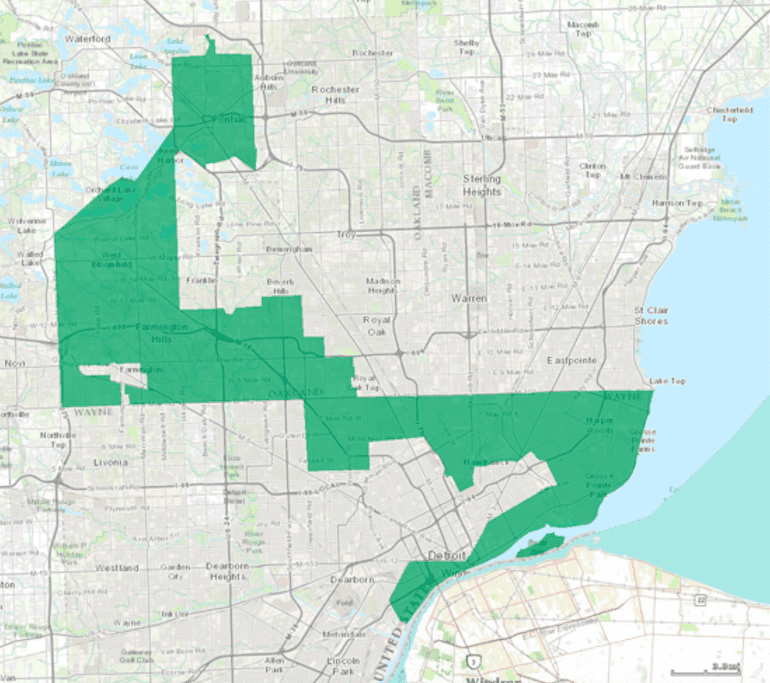

Michigan’s 14th congressional district looks like the arms of a bodybuilder flexing, with the right arm curling downward into Detroit and the left swooped up toward the city of Pontiac. Its ridiculous shape is designed to corral as many Democrats as possible into one district, to keep their voting power from sprawling across Michigan, one of the most gerrymandered states in America.

In two years, however, all that will change. Beginning in 2022, the same politicians who designed the state’s legislative districts to preserve their own political careers will sit on the sidelines as a new independent redistricting commission draws fairer boundaries. The change will correct an electoral flaw that has caused mass disenfranchisement, and will mark a dramatic transfer of power from entrenched politicians to the people of Michigan.

People power, in fact, is exactly what made this change happen. Michigan’s solution to its gerrymandering problem started with a group of political novices who decided to take matters into their own hands.

They launched Voters Not Politicians (VNP), a non-partisan non-profit that successfully developed Proposal 2, the ballot initiative that established Michigan’s independent redistricting commission. The commission is composed of randomly selected residents from across the political spectrum who will redraw the state’s legislative and congressional districts. By design, it excludes party insiders and politicians.

“A lot of people were ready to roll up their sleeves and fix things themselves because a lot of politicians and parties made promises that haven’t led to results,” said Katie Fahey, the founder of Voters Not Politicians.

Fahey’s journey to anti-gerrymandering crusader began shortly after the 2016 election. She was 26 years old, and everyone she knew seemed to be arguing over politics. Some had voted for Donald Trump, others had supported Bernie Sanders. Despite their ideological divide, they were united in one thing: their dissatisfaction with the political establishment.

Fahey started to ponder how that frustration could be harnessed to effect meaningful, positive change. It occurred to her that gerrymandering could be contributing to the anger on both sides.

“I was less thinking about a candidate and instead said, huh, I wonder if other people are really interested in ‘draining the swamp’ and having a ‘political revolution,’ but with these basic building blocks of democracy,” Fahey said. “I found out that yes, they were.”

After a few discussions, she posted on Facebook that she was interested in fixing Michigan’s gerrymandered districts and asked her friends and family for help. The response was overwhelming. By early 2017, Voters Not Politicians had formed as a registered nonprofit, comprised of change-seeking volunteers with political views as diverse as those from Fahey’s social circles.

Its volunteer ranks quickly swelled, and in the months that followed VNP fanned out across Michigan to hold dozens of informational meetings, gauge voter sentiment and promote their ballot proposal. Over 4,000 volunteers knocked on 125,000 doors and canvassed festivals and gatherings to collect the 400,000 signatures needed to get the initiative on the ballot.

The initiative passed with 61 percent of the vote in 2018. How it plays out from here is being closely watched by other heavily gerrymandered states. The commission’s success may lie in how it’s set up. Gerrymandering is a political maneuver in which politicians draw district lines so that “their voters” make up the majority in as many districts as possible. Whichever party controls the most districts writes the laws. In short, it’s politicians picking voters instead of the other way around.

Michigan’s new commission kicks politicians out of the district-drawing process. It will be composed of four Republicans, four Democrats and five Independents, all randomly selected. Party insiders, politicians and their families are barred from participating. The commission will draw legislative maps that reflect Michigan’s population and don’t offer an advantage to any political party. A simple majority of commissioners can approve a map, but at least two Democrats, two Republicans and two Independents must be part of that majority.

Fahey says the exclusion of politicians is what gives the commission its legitimacy. “It was all people who were looking for a way to participate because they feel anxiety over problems stacking on top of one another, and this was a way to work with people who wanted a systemic fix instead of help from a political party.”

This differs from some other “citizen-initiated” ballot proposals that are naked attempts by a political party or special interest group to pass legislation that promotes an ideology. This year, for instance, the conservative Right To Life Foundation is using such ballot proposals to attempt to push through highly restrictive abortion laws in Michigan.

The commission’s goal of creating “a redistricting system that’s fair to every voter in Michigan,” with no advantage for Democrats or Republicans, “was different in an age of skepticism,” Fahey says. “Those things are important for building trust and something that people could get behind. That’s what democracy is supposed to be about.”

VNP also succeeded because it focused on a single issue, says Fahey. Others have failed because they attempted to pass a package of related changes, but VNP zeroed in on one fundamental problem. “From my observation, it really helped us to have a single focus.”

Since the 2018 election, groups linked to Michigan Republicans have filed federal lawsuits that ask judges to strike down the commission, but those attempts have so far failed. VNP is defending the commission, but doing so without Fahey, who launched a new non-partisan non-profit called The People that helps residents in other states use the VNP model to enact structural change.

The People started by inviting 100 residents — two from each state — from across the political spectrum to Washington, D.C. to discuss systemic problems that residents could address. Like the early days of VNP, they were political novices. “Hardly any of them knew what reform issues were, but they knew that they were frustrated with the polarization and our government,” says Fahey.

So far, residents in Florida and New Hampshire are holding community meetings around the state to gather input on which issues to tackle, while a group in Virginia may help with redistricting reform in the state’s legislature or push forward with a ranked voting proposal.

More issues are likely to come, and Fahey says she’s seeing the same sentiment across the country that she saw in Michigan: “Regular voters want a system that treats people the same.”