Ali Qorbani first moved into his house in Hamburg in February 2021, more than two years after the 26-year-old Afghan arrived in Germany’s second largest city.

To have his own place, a spacious one-floor house in the leafy western suburbs of Hamburg, has “freed his mind” and brought “profound happiness” to the young refugee, who fled the Taliban. “I can decide how I want to live and work,” he says.

About 50,000 refugees live in Hamburg and more than half of them, like Qorbani once did, currently reside in public housing known as “camps.” They are supposed to be allowed to move once asylum has been granted, or if an ongoing decision has taken more than 18 months. But on average, refugees remain in these temporary solutions — which can be cramped and overcrowded — for more than three years. More than 12,000 refugees in Hamburg are currently eligible to leave, but have not.

Qorbani himself struggled initially, being forced to share a place with a roommate who, he says, had criminal tendencies and once physically beat him, leading to police intervention. “It was difficult to work and sleep,” he says. “It’s difficult for refugees to find apartments. There are a lot of hurdles.”

But Qorbani benefited from the initiative Wohnbrücke Hamburg, which launched in November 2015, and takes a pioneering approach to helping refugees integrate and find their own homes.

The nonprofit organization does not rent apartments itself but mediates between landlords or housing companies and refugees — a role that they see as important but often entirely lacking from the official asylum process. Each refugee must pair up with a chosen volunteer — who receives workshop training — to help them search for a house, deal with paperwork, physically move in and more generally acts as a “cultural mediator” and friend in a country and city that is completely new and largely alien to them.

“We want refugees to not only find a house, but a home,” says Alena Thiem, project coordinator at Wohnbrücke, whose four-person team carries out follow-up visits a few weeks after each move in. “There are always social codes that you learn growing up, but if you’re a refugee you didn’t have that and it’s not clear. That’s what we try to help them with.”

Hamburg’s crowded housing market makes it difficult to find a house, especially for foreigners. According to the city’s office for housing emergencies, 150 potential tenants are interested in every apartment that becomes available. Even though the city of Hamburg will pay up to €576 (about USD$630) of social housing support for one refugee, or €1,045 (about USD$1,145) for a house of four, the search can last months or years. The fact that many refugees tend to have larger families than Germans makes it even harder.

But Wohnbrücke Hamburg also directly consults private landlords across the city to find potential homes as well as reduce fears and prejudices about refugees that they might have — an issue that, they say, is not addressed by authorities.

Between November 2015 and October 2021, the project supported 3,012 refugees — who often come from countries such as Syria, Afghanistan and Iran — to leave camp and move into a home. At the same time, more than 1,000 volunteers have been trained as wohnungslotsen, or “apartment scouts,” learning legal basics and how to draft housing applications.

Petra Urban, a volunteer who works in public relations, wrote all the emails to Wohnbrücke for Qorbani and helped him apply for housing support from the government. “She’s more than a friend,” he says. “She’s like an aunt.”

Urban, who has supported four other refugees in Hamburg, met Qorbani in 2018 while volunteering for a separate charity and they struck up a friendship. She later agreed to become his so-called “apartment scout” and within a few months they found his new home.

“I’m always very happy when someone finds a place,” she says. “But I feel a large responsibility. I want it to work well. I am one of the first people he contacts when he has a problem.”

Weighed down by negative news?

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.However, under Wohnbrücke’s scheme, refugees must find their own volunteers. The expectation is that they might meet others at the same workplace or gym or daycare, but it can be challenging. “It is the first step,” says Thiem, acknowledging the potential difficulties. “They must not be too shy.”

Nonetheless, Urban says she’s taken a lot from the experience herself. “It makes me appreciate and thankful for the life I have,” she adds. “It’s humbling. It makes me understand the world a bit better. This is one of the biggest questions of society: how do we deal with migration?”

Failed integration can lead to unhappy, marginalized refugees and xenophobia from local populations, which makes finding a solution an enormous, growing challenge, according to Jenny Phillimore, professor of migration and superdiversity at the University of Birmingham. “The trajectory is very much upwards,” she says. “As conflict rages around the world, displacing more people from their homes by the day, it will only become a greater problem.”

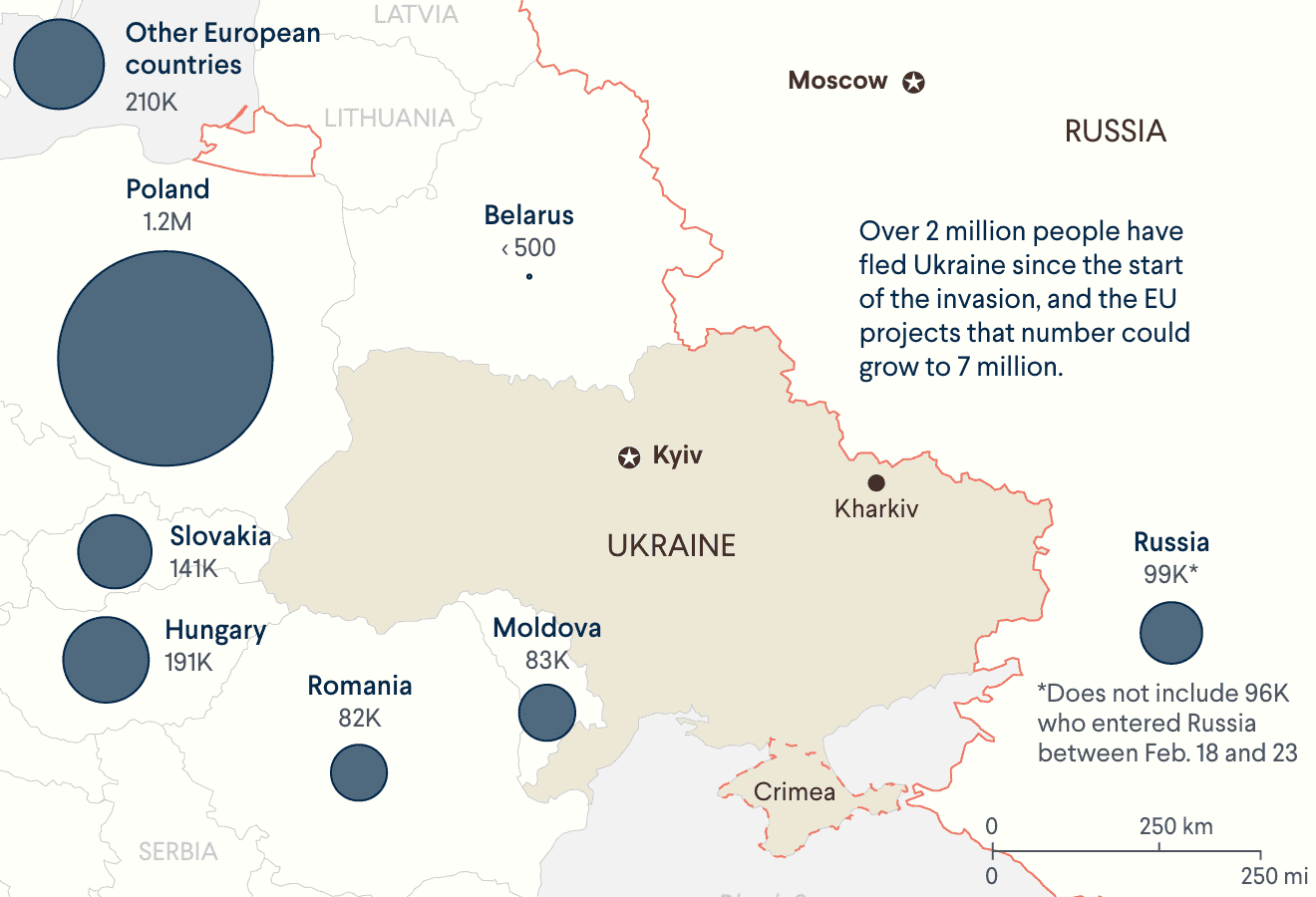

In 2020, there were 82.4 million forcibly displaced people in the world, according to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees — double the number just 10 years ago. In Hamburg, 5,538 refugees arrived in 2021, up from the 3,896 that arrived in 2020. Recent events in Ukraine and Afghanistan have seen those numbers rise further.

Yet Phillimore believes that Wohnbrücke is fulfilling a need in refugee integration that is often sorely missing from programs around the world. “Understanding institutional cultures is very tricky,” she says. “If you parachute anyone into a country where they don’t know or speak the language, it will be tough. But when local people work with refugees, the whole community becomes a lot more open.”

These provisions, she adds, should be an integral part of any government’s refugee integration system. “In an ideal world, this will be a function of local authorities,” she says. “It needs to be guaranteed for the long term. And it could also be extended to help all people in vulnerable situations, including those that are homeless.”

Fittingly, as a mark of Wohnbrücke’s initial success, more financing has arrived. In January 2021, it received three years of funding from the German TV Lottery, Deutsche Fernsehlotterie. In the future Wohnbrücke plans to expand its post-move services to refugees as well as hold social meet-up events.

For now, Qorbani is happy enough. Thanks to the steady foundations of his new home, things are on the up — he had been working in a bakery, but in January he began an apprenticeship as a dentist.

“To be in Germany is great,” he says. “But in Afghanistan, it’s important to invite people to your home, to welcome them as part of the culture. Now I can do it.”