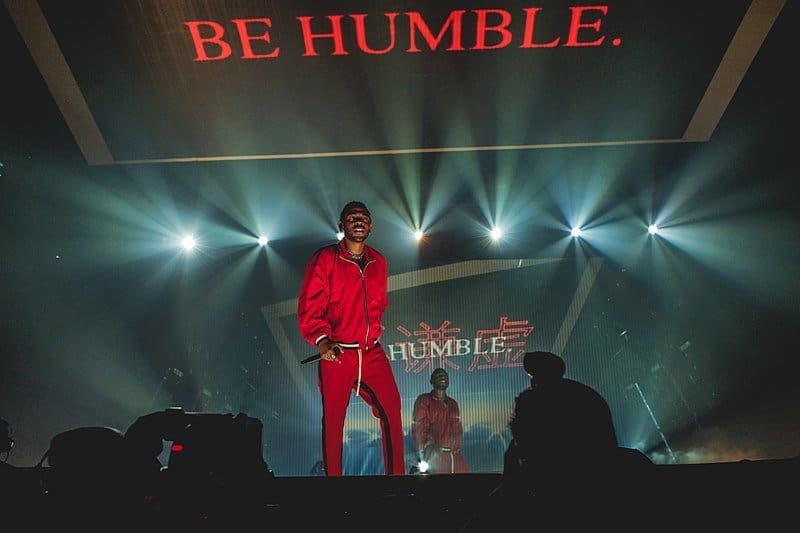

In the 2018 Grammys, Bruno Mars won the award for Best Album, beating out Jay Z, Lorde, Kendrick Lamar and Childish Gambino. But was Bruno Mars really who most voters wanted to see win that year, or did the votes for some of the other nominees cancel each other out?

I am a Grammy voter, and I voted for Childish Gambino, I seem to recall. My second choice would have been Kendrick Lamar… and I would have indicated that if the Grammys had let us rank our choices. If they had, Kendrick’s votes might have outnumbered Bruno’s, and Kendrick would have won. Had that happened, I might not have seen my favorite win the Grammy for Best Album, but at least someone near the top of my list would have won, and I would have felt that I had some meaningful say in the outcome.

But because the Grammys uses conventional voting, I only got one pick. My preferences beyond my top choice didn’t matter.

What if every vote counted?

Imagine a representational voting system that has nothing to do with political parties and that guarantees that the voices of we the people are heard. Such a system exists — in fact, it has been in use in various parts of the U.S. for some years now. More and more places are getting on board. It’s called ranked choice voting.

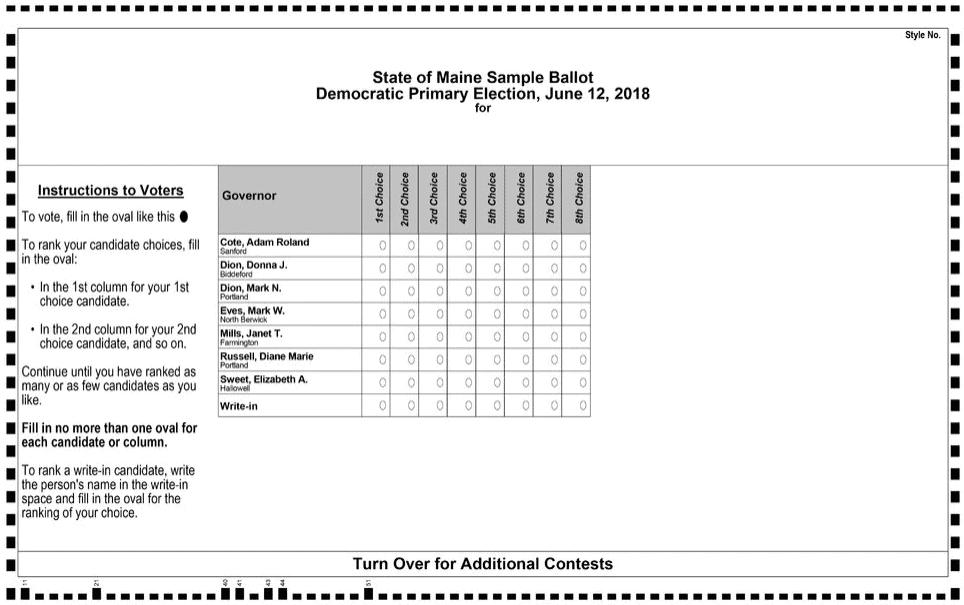

In ranked choice voting (RCV), rather than only voting for a single candidate in each category, voters rank their favorites (first, second, third, etc.) from a list of everyone running. You can pick any candidate, regardless of party, if there are even parties (there don’t have to be). If no candidate reaches a majority, the one with the fewest first-choice votes is eliminated.

What happens then? The folks who ranked that candidate first automatically have their second choice counted instead. This ensures that, while they may not get their first choice, their voice is still being heard. This process happens over and over until one candidate reaches a majority and is declared the winner.

A few states already use this system. Here’s an example from Quartz of how people’s second and third choices made a difference two years ago in Maine:

In 2018, after ballots were counted in Maine’s second congressional district, Democrat Jared Golden trailed Republican incumbent Bruce Poliquin by about 2,000 votes. But with the ranked choice voting system, Golden ultimately won by about 3,000 votes, picking up Democratic votes that initially went to independents Tiffany Bond and Will Hoar.

As we work together to reduce the number of Maine veterans experiencing homelessness, organizations like Cabin in the Woods are doing important work on the ground to help vets get back on their feet. pic.twitter.com/OIRbjXlPSF

— Congressman Jared Golden (@RepGolden) February 13, 2020

According to an analysis by the Bangor Daily News, Poliquin was the more partisan of the two candidates, voting with Donald Trump 97 percent of the time, whereas Golden, a Marine veteran who ran on a moderate platform, “has campaigned as pragmatic more than partisan.” So Poliquin, who was a bit more extreme, did not triumph, and Maine ended up with a more moderate congressman. The supporters of Bond and Hoar may not have seen their favorites win, but Golden’s victory shows that many of them picked him as their second choice, so they got a leader somewhat more aligned with their wishes.

What are the benefits of ranked choice voting?

It makes voters feel that their vote matters more

In ranked choice voting, the winner always has the support of half the voters even if he or she wasn’t the first choice of all of them. This prevents voters from feeling that their votes were “wasted,” as often happens in the present system.

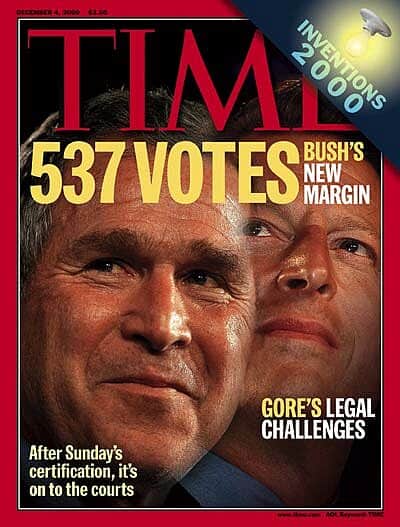

It eliminates the spoiler effect

In typical, winner-take-all voting, a “loser” can win simply because the majority of votes got split among a few other, similar candidates. For example, if the 2000 presidential election had used ranked choice voting, many of Ralph Nader’s votes in Florida would have automatically gone to Al Gore on the presumption that Gore would have been the second choice of most Nader voters.

Had this happened, Gore would have won that state — and the election. You can see why some politicians would prefer not to have RCV — its fairness doesn’t work well for them. If the supporters of that politician happen to comprise the largest individual slice of the pie — even if that slice is far less than half of the pie in total — then that person will win.

It helps reduce polarization and negative campaigning

As former presidential candidate Andrew Yang wrote on his website: “Since each voter can potentially vote for a candidate as well as their opponent, candidates shy from negative campaigning that would alienate the supporters of other candidates, instead trying to appeal to those voters as their second or third choice.”

It means fewer candidates are written off as unelectable

This could encourage a wider range of candidates to run for office, and more voters to cast their vote for them.

It eliminates primaries and runoffs

All candidates who qualify for the ballot are on there, not just the ones who survive the primary race. There are no primary races.

It eliminates swing districts or swing states because every vote matters

Swing districts and states are predicated on the largest individual pie slice after one vote taking the whole pie. With conventional voting, that can mean that a relatively small change in a pie slice can “swing” a whole area one way or another. With RCV, a “true majority” consensus results and a whole state or district is not represented by someone most voters don’t support.

It allows for more than two parties to actually matter

This happens because with RCV, since you have more than a binary choice, party affiliation isn’t necessarily what you’re voting for. And if you’re not voting strictly along party lines, then candidates not affiliated with either Democrats or Republicans might actually stand a chance.

What are the downsides?

Some politicians — particularly incumbents — complain about ranked voting. Maybe this is mainly because it reduces their advantage, but they do make a couple of valid points worth mentioning.

It’s complicated

Yes, ranked choice voting demands more of the voter than a simple binary choice — they have to decide how to rank a whole list of candidates.

It requires voters to know about the candidates

Sadly, under our current system, many people simply vote along party lines, but with RCV voters actually have to research and read up about the candidates and what they stand for. Otherwise, they won’t know who to rank in which slot.

Oddly, both of these “problems” might actually be pluses. If voters feel the need to educate themselves a bit more, isn’t that a good thing? Shouldn’t that be applauded? Shouldn’t we give voters a little more credit than some politicians are giving them?

Where is ranked voting already in use?

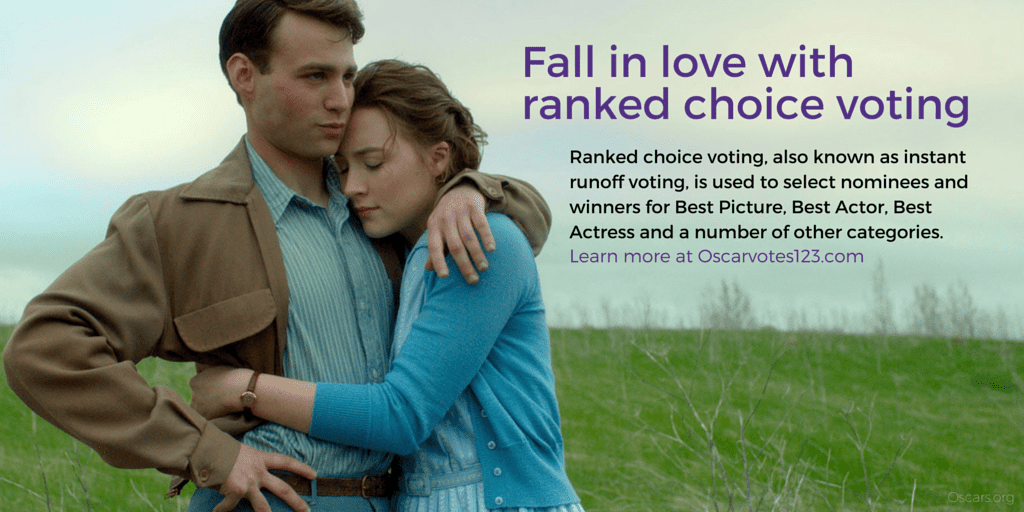

Ranked Choice Voting is not just about political decisions. As can be seen in the ad below, ranked choice voting is used by the Academy Awards in some of the key Oscar categories.

A version of ranked choice voting is also used in baseball to determine Most Valuable Players.

Voters assign players a rank using a point system called a Borda count. Everyone picks ten players for MVP — their top choice is awarded 14 “points,” their second choice gets nine points and so on. This is a slightly more sophisticated version of RCV, in that not all choices are equally weighted — first choices get more points than second choices, and so on. One criticism of this method is that folks could game the system by selecting only their first choice and no one else, but that has not happened. Strictly ranked choice voting would eliminate even that possibility.

Australia has been using RCV in their lower house elections since 1918, so this is not a newfangled idea. (Australia also has mandatory voting, but that’s another story.) Perhaps surprisingly, it was the conservative parties who pushed for RCV after losing when they split the vote in the second decade of the 20th century. Once RCV was implemented (it’s called preferential voting in Australia) the conservatives tended to dominate for a while, but that changed in the 1980s with the rise of the Greens and other small parties, whose representatives were able to gain seats in the government thanks to the RCV system.

RCV created more cooperation across the political aisle in Australia. Dominant parties and players often feel obliged to adopt at least some of the positions of smaller and opposing parties in hopes of being picked as second choice by their supporters. Polarization is lessened.

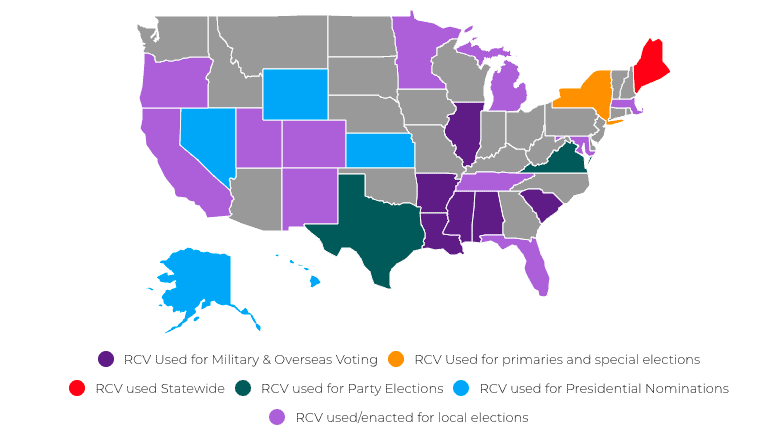

Maine has recently adopted RCV for all its elections, even federal ones — it’s the first and only state to have done so. Fifteen U.S. cities use ranked voting, the largest being New York, where voters recently approved a ballot measure instating it. (It will take effect next year.) Among the others are San Francisco, Santa Fe and Minneapolis.

Ranked choice voting seems to have clear advantages over the plurality winner-take-all system used in most elections. The main question would seem to be, will voters put in the extra effort required to make it work? I imagine there could be some initial hesitation or confusion (it is indeed a little more complicated) as there was in Maine. To deal with this, Maine Secretary of State Matt Dunlap made himself available on Facebook Live to answer voters’ questions. Folks there ended up feeling much more engaged and represented, and overwhelmingly voted in a second referendum to stick with ranked voting.