This story is part of Cool Project, a series about surprising ways cities are cranking down the heat in a warming world. Learn more about the series and the artwork here.

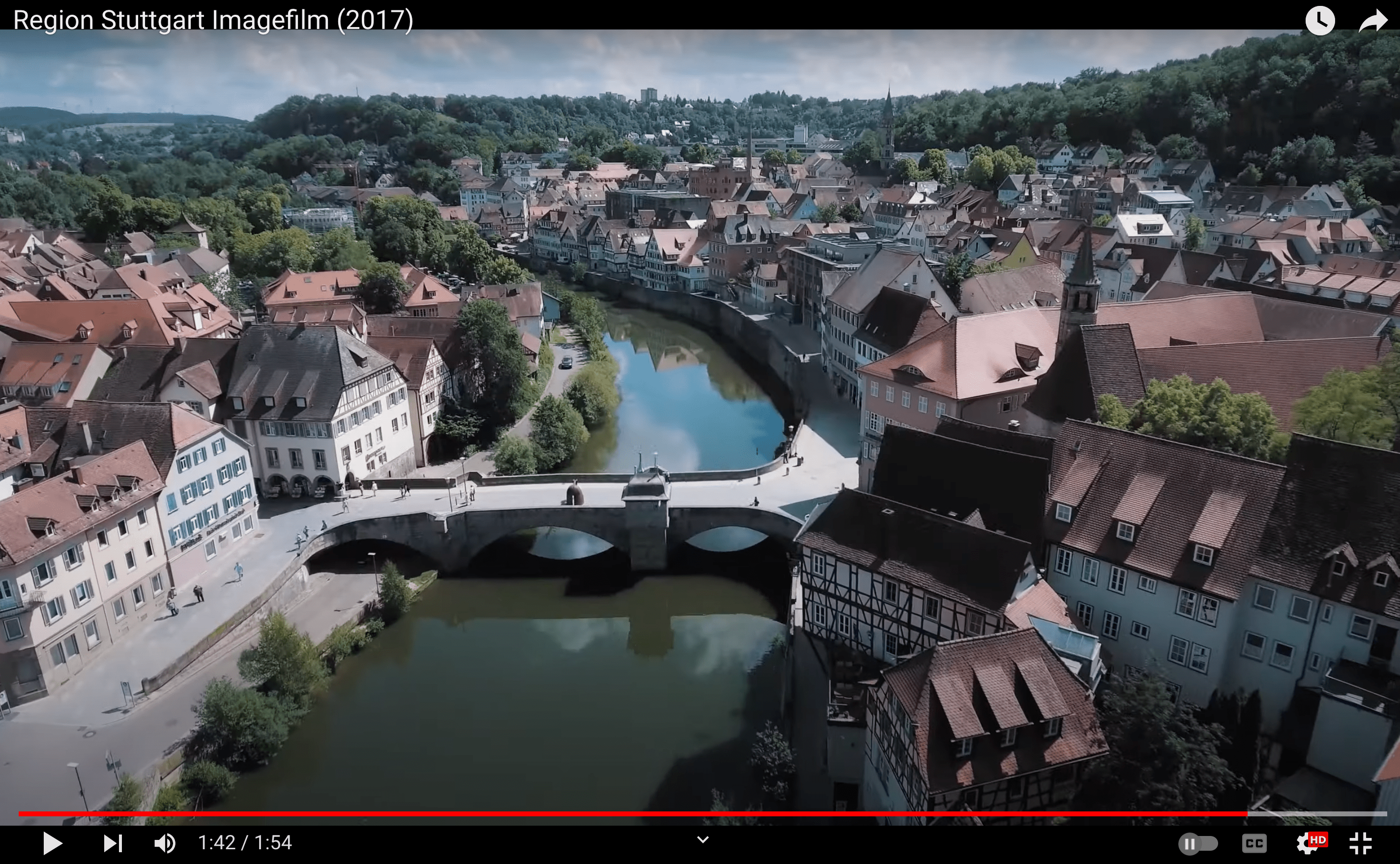

To travel through Stuttgart is to visit past sins and glimpse a promising future. This German manufacturing hub is where the gas-powered automobile was invented in 1886. Porsche and Mercedes still manufacture their luxury cars here, and these companies’ local museums celebrate a time when the chrome curves of sports cars symbolized speed instead of a climate crisis.

But when you drive into Stuttgart, descending into the city from the surrounding hills, you may notice an unusual feature of the urban landscape: tree-lined parkways and lush corridors of green. Like the cars the city is famous for, these corridors are the product of meticulous engineering — a vast network of ventilation channels that carry cool breezes from the chilly hills into the urban core.

Stuttgart may be the only major city in the world intentionally designed to cool itself with the naturally lower air temperatures that drape the terrain beyond its borders. It is a remarkable example of what scientists call “nature-based responses” to climate change — solutions that leverage the earth-cooling tools readily available to us in the natural world.

Clearing the way

Stuttgart’s cooling innovations are rooted in its geography. The city is in a relatively breeze-less, densely populated valley basin that traps pollutants from its manufacturing and traffic. Precisely because of this disadvantage, Stuttgart created the role of “city climatologist” in 1938, long before anybody anticipated a climate emergency more than half a century later. “Back then, people already realized that the air quality was questionable here,” says Rainer Kapp, the current chief city climatologist. “Of course, people didn’t have the ability or even the ambition to do much about it, but at least they started investigating and measuring it.”

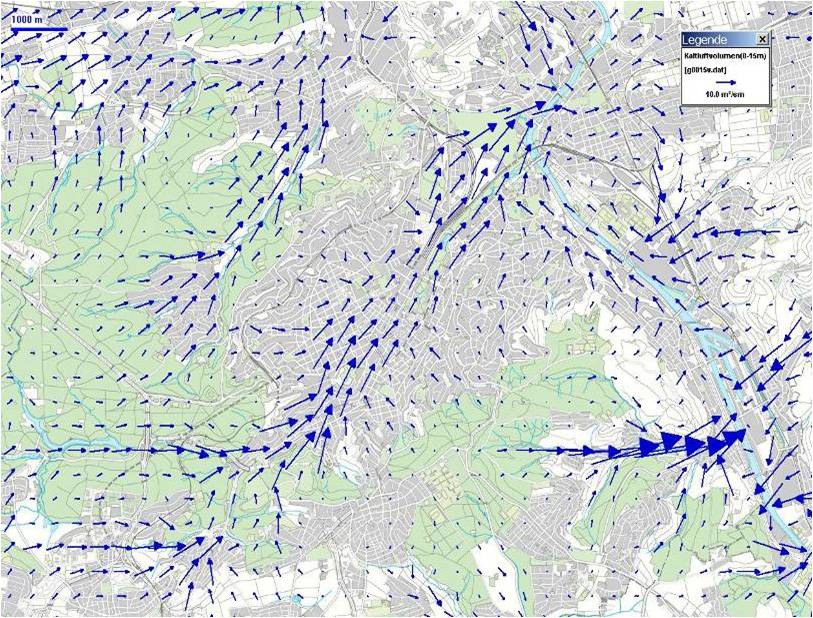

Because of this topography, Stuttgart is an average of two to three degrees Celsius hotter than surrounding areas. To combat this, for decades the city has been diligently protecting its “ventilation channels” — parkways and corridors of water and trees that funnel cooler breezes into the city at night. Some of these corridors are planted atop abandoned transportation infrastructure, like old railway lines, which the city has turned into green belts or waterways to create a network of interconnecting parks.

Even hard infrastructure can work as a ventilation channel, as long as it can funnel into the city the natural wind patterns that swirl in the higher elevations beyond. “Usually [the corridors] are green spaces, but it can even be a road that hardly has any traffic at night,” Kapp explains, comparing it to “opening the windows at night in your apartment to let the fresh air in.”

The design of Stuttgart’s ventilation channels has been guided by a map of its urban climate that was first drawn up by the climatology office in 1998. More maps have followed in the time since, showing wind patterns, flows of cool air, air pollution concentrations and urban hot spots, providing a blueprint for dealing with the heat problem.

These efforts have earned Stuttgart the moniker “coolest city in the world.” Nearly two thirds of the city — a total of 207 square kilometers, inhabited by more than 630,000 people — is green space, and nearly half of that is forest. “Stuttgart is a forerunner in the protection of green spaces,” wrote the World Wildlife Fund in 2012. “Using green ventilation corridors and construction bans at strategic places, Stuttgart has not only protected its climate with winds that hinder overheating. It has also improved air quality and increased resilience against global warming.”

By now, other cities have climatology offices, too, but Kapp’s is staffed with an impressive 13 employees, an indication of how seriously the city takes the issue. Among the office’s responsibilities are ensuring clean air quality, reducing traffic noise and addressing urban heat islands. What sets Stuttgart apart is that the city routinely integrates climatic concerns into urban planning. Building permits, development proposals and infrastructure projects are scrutinized against the cool-air mandate. Kapp admits it’s a constant battle balancing the city’s demand for housing with its need to keep the breeze flowing freely.

“When someone wants to build apartments, we often have trouble showing the exact obstacle a row of houses will be to the air flow,” Kapp admits, “but overall, we are able to prove in detail that extending buildings in certain spaces limits the exchange of air.” Within the city, some hillsides have been marked off-limits for real estate developments. “We’ve even rescinded building permits,” Kapp says, but given the city’s high real estate prices, such moves often involve lengthy court battles.

Kapp’s job is made easier by Stuttgart’s long history of sustainable building practices. Since the 1990s, the city has implemented climate-friendly building codes — today, all public buildings are required to produce more energy than they consume. In 2022 Stuttgart won the German Sustainability Award as Germany’s most sustainable city. This is in part the legacy of Fritz Kuhn, the former chairman of the Green Party, who was Stuttgart’s mayor from 2013 to 2021. And this year, the city pledged to become carbon-neutral by 2035, releasing a holistic plan that includes all of its industries and allocating 300 million euros to achieve its goals.

Stuttgart was also an early adopter of green roofs and “cool” buildings. Financial incentives begun in 1986 have resulted in an impressive 2.6 million square meters of green roofs. Soon, citizens will be able to look up online whether their roof is best suited for solar panels or green space. Another impressive example is the local library, a landmark on the city’s skyline and, according to the same study, “the coolest library in the world.”

Kapp, an engineer by training, has been with the climatology office since 1993, and while he admits that “we were often not taken seriously in the early years,” citizen support has increased enormously amid heat waves and floods. Stuttgart now has some of the most active citizen participation in city planning nationwide. For instance, by popular demand, “cooling busses” traverse the city in the summer to pick up people experiencing homelessness so they can get some sleep and recover from heat stress, similar to the heated busses that provide warm space in winter.

Citizens can also request that a local street be designated a low-traffic zone and its parking lots transformed into green spaces, simply by downloading an online application. Entire streets have been reserved for bicycles. And though construction of the city’s new energy-efficient train station resulted in brutal clashes between citizens and police over the removal of several old trees, efficient public transport is another model project in the city.

Kapp admits that not every city has the topography required to replicate what Stuttgart has done, but some do. He is in contact with the mayor of Kobe, Japan, another city flanked by hillsides. Even Beijing and Xian have begun studying their own wind patterns to determine if they can copy Stuttgart’s ventilation corridors.

Where once cars ruled, bicyclists and pedestrians are increasingly taking over, and the birthplace of the gas-powered automobile is becoming the cradle of a responsible climate future.