When I entered my friend’s newly built guest house near San Diego, I admired the broad glass front that opened up to a panoramic view over the valley. By the time I left an hour later, an egg-yolk-yellow warbler was writhing in front of the glass entry door. We took the barely breathing beauty to a bird rehabber who told us it would not survive.

According to an often-quoted estimate, building collisions kill a billion birds in the U.S. every year, plus 40 million in Canada. But the true figure is likely three to five times higher. The latest research indicates that many more birds fly into windows, manage to dart away and die later from concussions or internal injuries. These have not been counted.

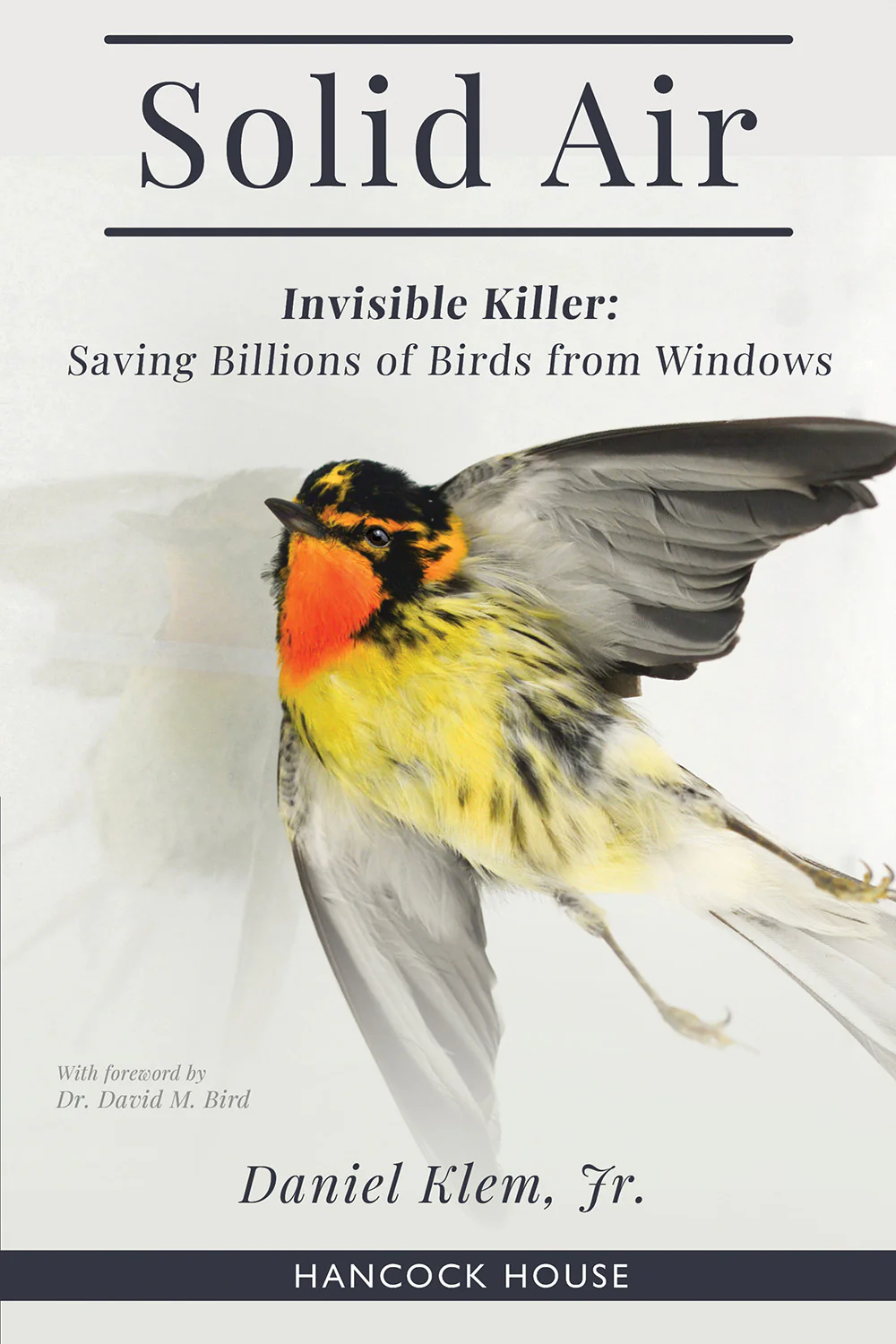

Daniel Klem, the Sarkis Acopian Professor of Ornithology and Conservation Biology at Muhlenberg College in Allentown, Pennsylvania, was the first to comprehensively study and sound the alarm about the “really senseless killing of these birds” in the 1990s. He found that collisions with glass kill up to 5.19 billion birds in the United States each year, with potentially billions more worldwide. “That means 3.5 million die from striking windows every day of the year,” he explains. “And this killer is indiscriminate — taking the strong as well as the weak, creating environmental devastation. Window-killed victims are innocent and helpless casualties because they are not able to see them as barriers to be avoided; moreover, they have no voice or means to protect themselves from this invisible killer.” Klem wrote the book Solid Air, Invisible Killer: Saving Billions of Birds from Windows to raise awareness because, as he puts it, “They must rely on us humans to act on their behalf to save them.”

Muhlenberg’s Acopian Center for Ornithology is stacked with trays containing hundreds of dead warblers, hawks and falcons, many collected after fatal collisions. Birds cannot see glass as a barrier, especially since their eyes are usually focused sideways. “We need to address this to protect these animals,” Klem urges. “This is a conservation issue that is important for birds and people. Everyone can prevent bird-window deaths and make an immediate difference.” Klem’s research also shows that the collisions occur year-round, and are not just concentrated during migratory periods.

The issue is critical. In a sweeping 2019 study, Cornell University diagnosed the long-term loss of at least 29 percent of breeding adult birds across North America — more than three billion birds. The study authors call this “a staggering loss that suggests the very fabric of North America’s ecosystem is unraveling.” Collisions with human-made barriers, primarily glass and cars, are a leading cause of bird deaths, especially for migratory birds that land in cities during their long journeys. Only cats kill more birds than glass windows. Habitat loss and power lines accelerate the birds’ demise.

Weighed down by negative news?

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.What bugs me most is that these deaths are so easily preventable.

I had heard of this issue but assumed it was mainly the fault of glossy high-rises. While it’s true that some particularly dangerous high-rises can kill thousands of birds in a day, I was shocked to learn from speaking with Audubon experts that low-rises with four stories or fewer account for more than half of bird collisions (54 percent), closely followed by residential structures (44 percent) and less than one percent at high-rises. This means that even if you and I never design a convention center, we have simple solutions at our fingertips for the problem that’s literally right in front of our eyes.

- Put something on the glass

“The first thing to address is the windows because it’s such a ubiquitous issue,” shares Keith Russell, an ornithologist and program manager for Audubon’s urban conservation program in Philadelphia. “As the amount of glass in buildings continues to grow fast and new buildings continuously go up, the danger for birds keeps increasing.”

DIY options for homeowners and renters could be as simple as “closing blinds, curtains or keeping screens on problematic windows,” Russell suggests. “You can buy inexpensive film that leaves small vinyl dots or patterns on windows to deter birds.”

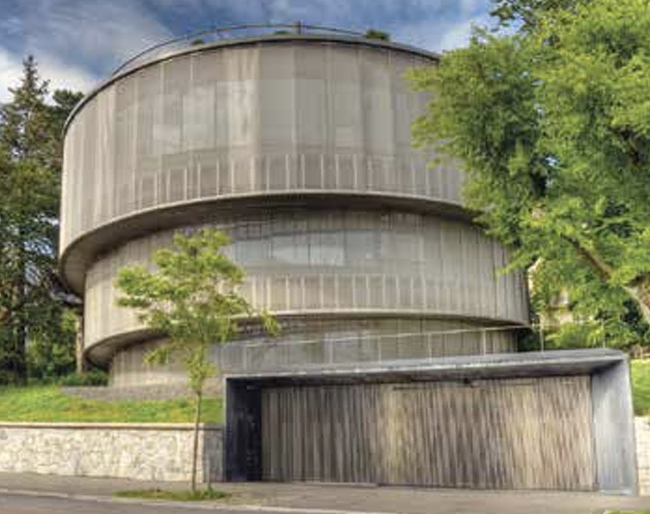

Philadelphia was the first city in the U.S., maybe in the world, to start monitoring and investigating bird collisions after birdwatchers noticed dead birds around City Hall’s tall, lighted tower in 1897. Audubon’s Philadelphia Discovery Center, which sits near a historic reservoir that provides habitat for 150 bird species, now showcases creative solutions, including acid-etched glass with permanent markings. Humans barely notice the tiny dots, but our feathered friends avoid them.

Collisions tend to occur more frequently with migratory birds like songbirds, woodpeckers, owls and raptors. Patterned or coated glass allows them to evade collisions. Putting vegetation or bird feeders close to windows is another deterrent, giving avian migrants a place to land instead of continuing at full speed toward the glass.

Chicago and New York, both situated along major migration routes, have transformed some of their death traps into effective and stunning examples of solutions. In New York, after the gleaming glass facades of the Jacob K. Javits Convention Center had been killing about 5,000 birds per year, architects reduced the amount of glass and replaced the rest with fritted glass, meaning small dots baked into the glass alert the birds. Additionally, a large green roof invites birds to forage or nest. Chicago’s 82-story Aqua Tower features an undulating, irregular façade designed by architect Jeanne Gang, an avid birdwatcher, “to work for both humans and birds.” While a few cities, including New York City, Washington and San Francisco, have enacted legislation mandating bird-friendly glazing for new buildings, most initiatives are voluntary. Despite New Yorkers mourning the untimely death of Flaco, the adorable Eurasian eagle-owl that escaped the Central Park Zoo, after a building collision, the statewide FLACO (“Feathered Lives Also Count”) Act, which would require bird-friendly designs, never passed.

The most elegant solution involves ultraviolet patterns on glass because most birds can perceive them, but humans can’t. Russell cautions, however, that it needs to be sunny for the ultraviolet patterns to reflect effectively: “It doesn’t work as well when it’s cloudy, foggy or dark.”

Russell mourns the disappearance of birds like the red-and-black scarlet tanagers he spotted in flocks 10 years ago and now rarely sees, but he celebrates small victories. “I think we can overcome this debacle we’re going through with building collisions if we act soon enough before these birds go extinct,” he says. “Every building counts.”

- Lights out

Birds easily get disoriented by excessive lighting. Since 1999, Audubon has been partnering with cities and building owners, urging them to turn off or at least limit unnecessary lights, especially during migratory seasons. Light pollution strongly influences where migrating birds stop. “Basically we want people to turn off their lights between 11 at night and 6 in the morning,” Russell says.

The Lights Out initiatives save birds, energy and money — for both residential and commercial building owners.

- Plant native plants

To help counter the disappearance of bird habitat, Russell emphasizes the importance of planting native plants that native birds often depend on. “This is a real problem in urban areas because people target ground vegetation for removal, leaving the birds nowhere to land and find food,” he notes. Providing native ground vegetation is “very helpful,” according to Russell. He is less enthusiastic about birdhouses and bird feeders, as most birdhouses attract non-native bird species, and he only advocates bird feeders during harsh winter months.

- Stop calling your pest management company

I’ve asked our landlord not to spray our small yard with pesticides during the monthly routine visits of the pest company. While my spouse gripes about the occasional spider or mosquito in our bedroom, the truth is, you can’t kill bugs selectively: Most pesticides don’t distinguish between beneficial and annoying insects. Studies report a decline of 75 percent in the biomass of flying insects over the last 25 years. Bugs make up most birds’ diets, and our yard is now bustling with orioles, warblers and the occasional hawk.

- Keep your cat indoors

I love cats, and this last point pains me, but cats have long been called the biggest bird killers, responsible for wiping out a third of them. Professor Klem points out that cats often scavenge weakened birds after window collisions. These deaths could be prevented by keeping cats indoors — or at the very least neutering and spaying them, and sabotaging their hunting skills by placing a bell on their collar.

As Keith Russell says, “Nobody is out of the loop in terms of their responsibility. There is no excuse.”