This is part one of a two-part series. Read part two here.

Sperm whales don’t sing melodious, moaning whale songs like their humpback cousins. The biggest predator on the planet communicates in clicks, called codas. Some compare the sounds to popping popcorn or frying bacon in a pan. For CUNY biologist David Gruber, it resembles “morse code or techno music.”

Gruber, the founding president of Project CETI, the Cetacean Translation Initiative, often listens for hours in his New York office to the sperm whale chats his team has recorded in the Eastern Caribbean.

CETI focuses on sperm whales for several reasons. One reason is that it can build on the audio recordings that whale biologist Shane Gero has already been collecting for 15 years with the Dominica Sperm Whale Project. Gero was able to show that sperm whale families have different dialects, much like British and American English. “Another reason is that the sperm whale has been vilified as a killer, Moby Dick as a leviathan,” Gruber says. “Meanwhile it could be one of the most intelligent, sophisticated communicators on the planet.”

While the humpback whales sing their soprano songs primarily for mating, sperm whales are communicating to socialize and exchange information. CETI has already discovered that the communication patterns are complex. “Their codas are clicks, they are like ones and zeros, which is very good for cryptographers,” Gruber explains. “The combination of advanced machine learning and bioacoustics is slated to be the next microscope or telescope in terms of our ability to really listen more deeply and understand life at a new level.”

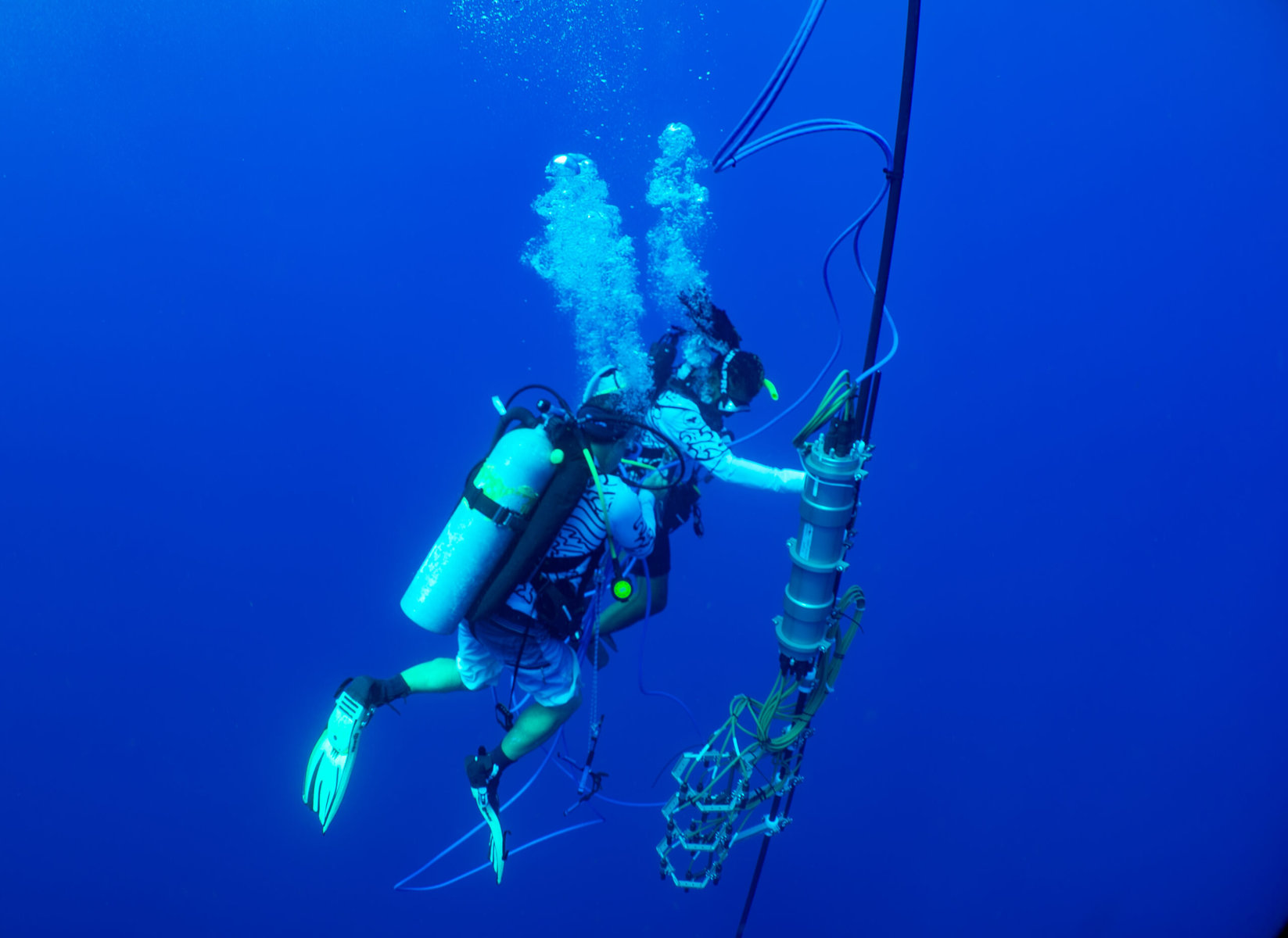

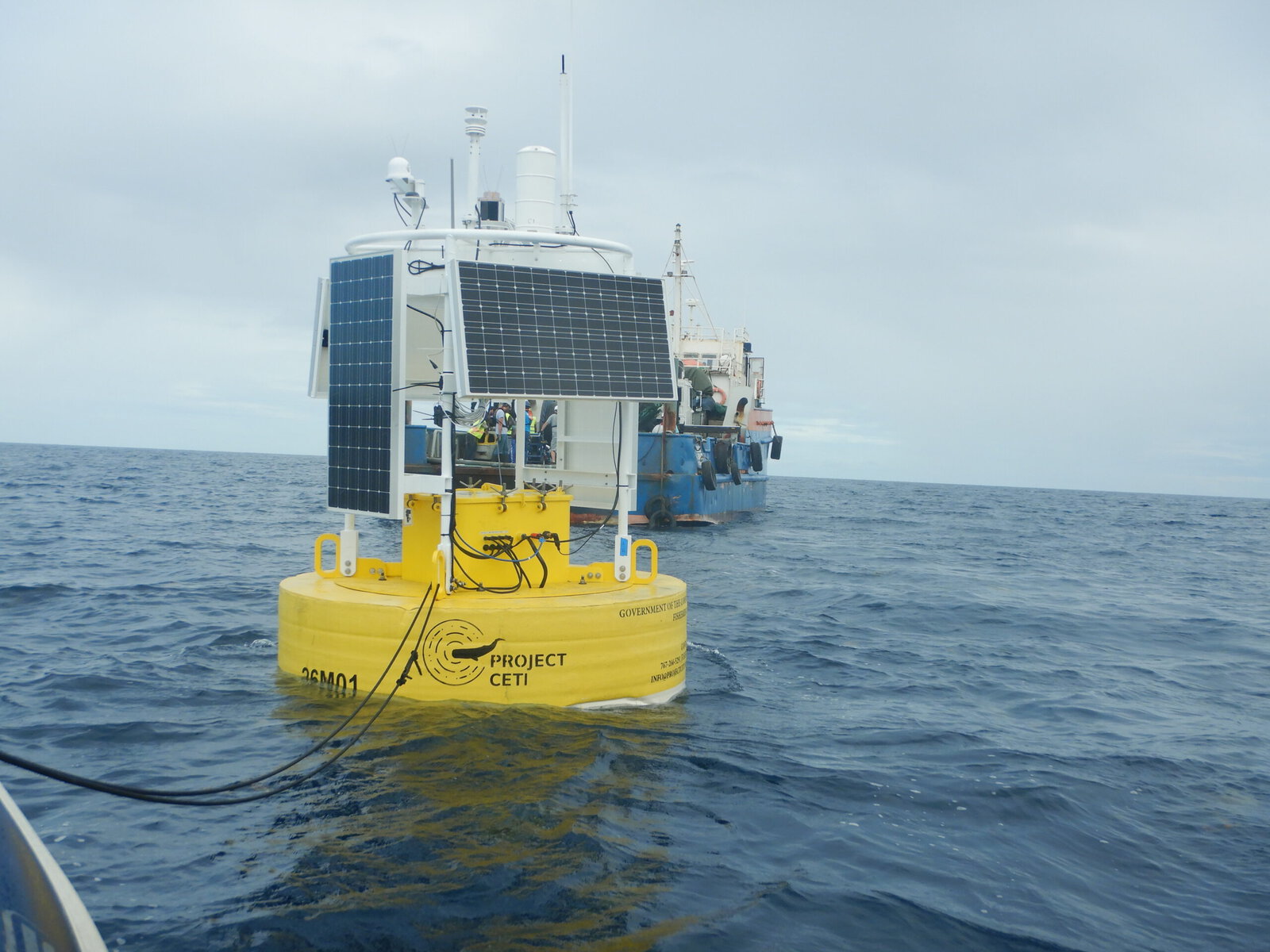

CETI’s team operates a giant whale-recording platform from a 40-foot sailboat off the coast of Dominica, a volcanic island in the Caribbean with a stable sperm whale population. Both by tagging the whales and installing whale listening stations with microphones dangling deep down into the ocean on floating buoys, CETI is recording several terabytes of data every month. The scientists are creating a three-dimensional interactive map of the whales within a 20-kilometer radius, combining sounds with data such as the whales’ heart rates.

His team is about to publish two peer-reviewed papers that show for the first time not only that sperm whales use vowels and diphthongs in their chats but also that their communication system has a far more complex structure than previously thought.

And not least, CETI focuses on sperm whales because though commercial whaling stopped in the late 1980s, sperm whales are still federally listed as endangered in the US. Ship strikes, entanglements in discarded fishing gear and pollution count as major threats. There are currently no legal protections for sperm whales in Dominica. “The fear of this project is that the whales disappear before we really understand them,” Gruber says.

The late bioacoustician and CETI advisor Roger Payne was instrumental in recording the songs of humpback whales in the late 1960s. Selling more than 100,000 copies, Songs of the Humpback Whale became the bestselling environmental album of all time. The whales’ voices moved millions of people and led to the creation of the Marine Mammal Protection Act in 1972, which ended commercial whaling.

“Now the idea is, well, what if we can understand what they’re saying?” Gruber asks. “How would that move us?”

CETI is partnering with the More Than Human Rights Project, which advocates for granting non-humans more rights. Toward that end, artificial intelligence is not only helping researchers understand animals better but is already being used to protect them. Turns out it is actually easier to monitor whales acoustically than visually because whales spend hours deep under water. For instance, in the San Francisco Bay and the Santa Barbara Channel, a passive AI-powered system has been installed to prevent ship strikes by alerting ships to the mammals’ presence. Whale Safe relies on human sightings as well as the acoustic detection of whales to identify, classify and report the sounds of blue, humpback and fin whales in near-real-time.

Another AI enterprise, the Earth Species Project, hopes to create dialogue with other species and build chatbots that could translate human language into hummingbird or humpback.

“Humanity may be on the brink of inventing a zoological version of Google Translate,” Karen Bakker, who led the Smart Earth Project to find digital solutions for environmental problems, explains in The Sounds of Life. “Western scientists assumed turtles [and many other animals] were mute and deaf. It was humans, as it turns out, who were the ones who couldn’t hear.”

Gruber compares the process of decoding the sperm whale clicks to the birth of the sperm whale baby he recently witnessed off the Dominican coast: “We feel like the baby whale in that we’re learning one little piece at a time, forming our first impressions of this world. How did this creature for 30 million years live and sleep and find food a mile down? There is a mountain of mysteries.”

It’s no accident that the name CETI echoes SETI, the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence. “It’s a trial run,” Gruber says, “a deep listening to our earth. Imagine we found some form of life in a faraway galaxy, we would need these tools so we could understand other forms of life.”

What we learn from these fascinating creatures could change the world.

All scrolling images are by Amanda Cotton. Recordings appear courtesy of the Dominica Sperm Whale Project and CETI.