“Why an Indianapolis district turned to bus drivers to keep students on track” was originally published by Chalkbeat, a nonprofit news organization covering public education. Sign up for their newsletter here.

On a recent morning, several Wayne Township high school students missing class received wake-up calls. But it wasn’t a teacher calling, or a counselor. It was school bus driver Erica Woods, working double duty as a case manager to support students.

She’s part college-prep guide, part mom and part cheerleader, even reminding them to breathe and drink water. “I need you to come to school everyday,” Woods told the students. “This is no joke.”

To keep high school seniors engaged and on track to graduate amid the pandemic, Wayne Township officials turned to a previously untapped resource: hourly employees still on payroll, but with time on their hands because students had switched to learning virtually.

Woods is one of 17 classified employees, or hourly staff, who served as the primary liaison for about 900 of the Indianapolis district’s seniors during eight weeks of virtual learning earlier this year. To safeguard against the pandemic, students learned remotely from November 16 to January 26.

District administrators said the experiment was so successful that it will continue with 10 employees, even though high schoolers have moved on campus two days a week.

Wendy Skibinski, Wayne Township’s director of college and career readiness, said the district came up with the idea last summer after seeing the effects of high school students losing the in-person support they usually had.

“We had to think about how we were going to accelerate the class of 2021 and get them up to speed,” Skibinski said. “All of the things that we typically would have done last spring, they missed out on all of that.”

Wayne Township, like other districts, allowed younger students more in-person learning and social contact than older students got, because science points to Covid not spreading in elementary schools as much as it does elsewhere. Many high school students nationwide have received very little in-person instruction since the onset of the pandemic a year ago and have been socially isolated during a pivotal time in their lives.

Weighed down by negative news?

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.From April to October last year, mental-health related medical visits increased among 12- to 17-year-old children by 31 percent compared with previous year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Wayne Township recognized the stresses facing many high school students: jobs to support their families, parents who lost work, financial aid and college applications, resumes, mock interviews and graduation — all without in-person help from overworked counselors.

Wayne’s high school student-to-counselor ratio is 475 to 1. The American School Counselor Association recommends schools have a 250 to 1 ratio. Skibinski said the district couldn’t afford to add more counselors in the middle of a pandemic.

District officials worried students would fall even further behind after Marion County ordered campuses to close in November.

At the same time, Skibinski said the district wanted to retain employees who weren’t able to work in a virtual environment.

The district previously found creative ways to mobilize those workers. Last March, it assigned its bus drivers to distribute meals to students at more than 1,000 bus stops.

So last fall, Skibinski solicited volunteers among paraprofessionals and transportation staff and trained them in college and career readiness support, interpersonal skills, technology tools, the college-guidance software Naviance, and resource tools on Google Drive.

District officials wanted case managers to build relationships with students, address their basic needs and make sure they had tools like technology, space and an organized schedule. Case managers check on grades and make sure students complete their assignments. Sometimes they help them with classwork. Their responsibility has evolved.

“It really started to morph,” Skibinski said. “Every day at 2:30, we would debrief. What are the kids asking for? What do they need? What do we need to provide more of?”

During the eight weeks of virtual learning, case managers earned their regular hourly wage. Now, as some of their previous duties have resumed with hybrid instruction, case management pays a $15 hourly stipend. Wayne Township, which is expected to receive nearly $16 million in its second round of Covid relief funding, approved $16,000 toward the program for the remainder of the school year.

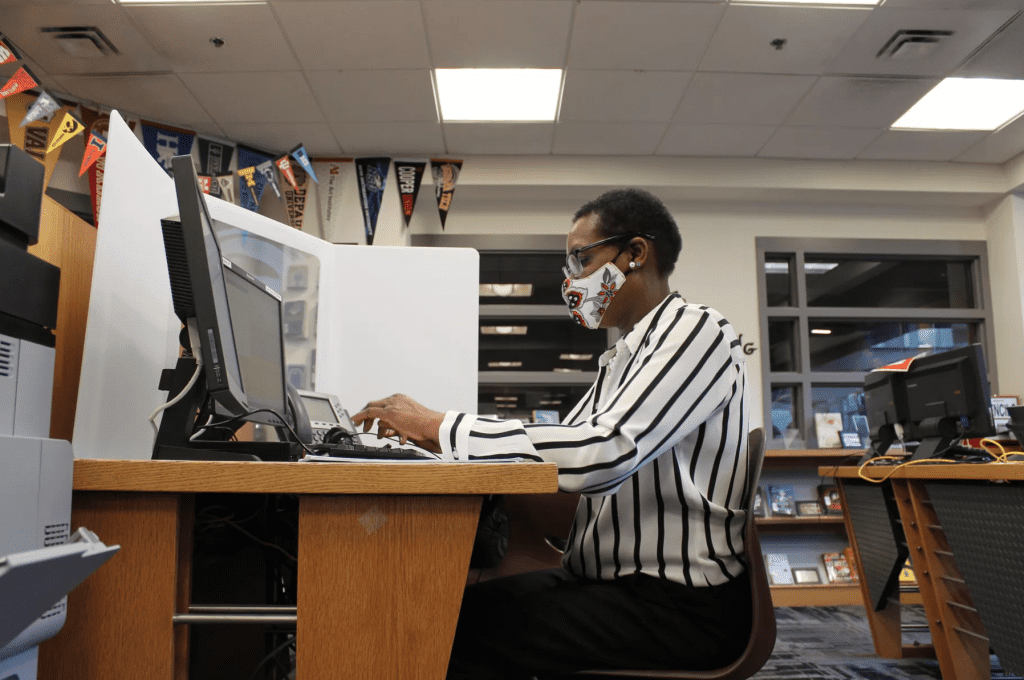

Woods has resumed driving a bus, starting around six a.m. every day. In between picking up and dropping off students, she’s checking her Galaxy 20 tablet for emails from students and calling students who may take evening classes. After work, she may spend a couple of hours checking and responding to student emails.

Last Saturday — when students were more reachable — she was online by 11:30 a.m., calling, emailing and updating her color-coded spreadsheet with information on the 41 students she is responsible for.

“There could be maybe 10 to 15 doing magnificent,” Woods said. “My focus is to make sure that the rest of them are coming along, making sure that their needs are met. I will ask them, ‘Hey, can you do an assignment a day? This needs to be done before March.’”

Skibinski said the pandemic has been terrible for everyone, but Wayne Township’s experiment has worked well enough to continue.

“We can’t let Covid be the reason why we’re not successful,” Skibinski said. For students, “We’re going to walk alongside you because our ultimate goal is for you to graduate, but also for you to do whatever it is your post-secondary goal was.”

Woods, a grandmother of seven and a bus driver for 24 years, feels she’s come into her life’s work. She hopes now to earn a teaching credential.

“There’s a need that needs to be met,” Woods said. “I enjoy being around people. Helping has always been my passion.”

This story was originally published by Chalkbeat, a nonprofit news site covering educational change in public schools.