California’s environmental achievements are something to behold. The state ranks first in the U.S. for growth in solar power generation and battery storage. It’s the national leader in cumulative electric vehicle sales and public EV charging stations. And it’s one of a growing number of states that aim to run entirely on carbon-free energy in the coming decades – a goal it briefly met, for about 15 minutes, on April 30.

Now, California is once again setting the pace on a critically important (if somewhat less glamorous) climate imperative: urban composting.

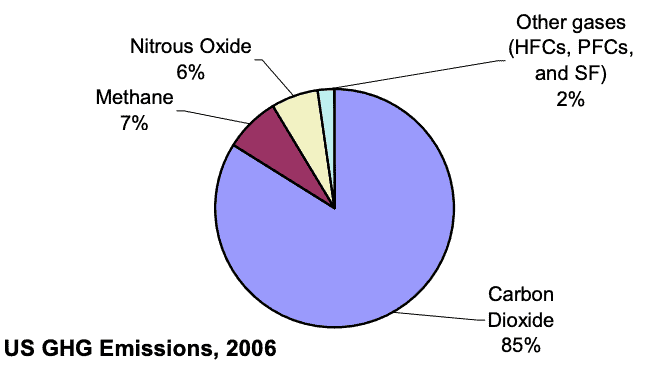

On January 1, a law went into effect making it mandatory for every city and county in California to provide residents a means to separate and recycle their organic waste. The impacts could be enormous – according to climate experts, composting is one of the simplest low-tech measures humans can take to reverse climate change. Allowing food waste to decompose in landfills creates methane, a greenhouse gas dozens of times more potent than carbon dioxide. And landfills are the third-largest source of methane in the U.S. Composting has other benefits as well, from sequestering carbon and helping farmers create drought-resistant crops to creating long-term revenue streams for city governments.

Yet few big American cities have successful city-wide composting programs, particularly on the East Coast. How does a city fully integrate composting into its sanitation stream? Perhaps nowhere offers as clear a path forward as San Francisco, the first big U.S. city to offer composting to all of its residents. Twenty-six years later, its system remains the gold standard.

Building a system scrap by scrap

In 1990, when curbside recycling was still new to many communities, San Francisco was already recycling over 25 percent of its trash. Nevertheless, the city’s Department of the Environment was concerned about all the garbage still being sent to faraway landfills, so it authorized a “waste characterization” study in 1996 in which engineers looked at exactly what was being sent to the dump. What they found was shocking: 33 percent of it was organic material that could have been composted.

Weighed down by negative news?

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.“It was a combination of food scraps, sticks and leaves,” says Robert Reed, public relations manager at Recology, a resource recovery company that partners with the city. “We have 5,000 restaurants here, so we’re generating a lot of food scraps.”

All those scraps add up to a heap of emissions, plus the associated costs of disposal. “When you put materials in a landfill, you eventually fill that landfill and you have to build another landfill. And now you have to ship to greater distances,” says Reed.

So, at the city’s request, Recology, which has collected San Francisco’s refuse since 1921, launched a compost pilot program. It started at the San Francisco Wholesale Produce Market and on residential routes in the Richmond District. Soon after, it expanded to include some large convention hotels. By 2000, it had gone citywide.

Nine years later, when cities like Seattle were just beginning their voluntary residential composting programs, San Francisco made composting and recycling mandatory for all residents and businesses.

Mandatory participation scaled things up dramatically. Recology began offering free composting pails, bin labels, signs, multilingual trainings and toolkits for commercial buildings. It also meant occasional fines from the city for non-compliance. All of it was part of the city’s ambitious plan to be “Zero Waste” by 2020.

Today, San Francisco’s pioneering program is world renowned. Over 135 countries have sent delegations to study the city’s compost and recycling systems first hand. The city collects more than 500 tons of compostable materials from its ubiquitous green bins every day, according to Reed, helping to divert some 80 percent of the city’s waste from landfills. All these organic scraps are turned into high-quality compost in just 60 days at a Blossom Valley Organics facility east of the city, and then sold to local farms, vineyards and orchards.

The revenue from these sales helps offset the cost of the program. “If something goes into the landfill, there’s no sale!” laughs Reed. The system also creates jobs. According to a study by the Institute for Local Self-Reliance, composting sustains four times the number of jobs as landfill or incineration disposal operations. In Maryland, a 2013 study found that composting operations provided more total jobs than the state’s three trash incinerators combined.

And of course, all that compost enriches the region’s soil with nutrients, minerals and microbes, helping farmers grow healthy crops with fewer commercial fertilizers. Compost also acts as a natural sponge – Pennsylvania’s Rodale Institute found that farms can grow up to 40 percent more food in times of drought when they use compost and follow other organic practices. In the West, where drought is common, this is a boon to both commercial farmers and backyard gardeners. Compost can even mitigate the threat of wildfire by retaining moisture from rain and irrigation.

All of which begs the question: With the many obvious benefits and few apparent downsides, why, 26 years after San Francisco started composting, haven’t other major cities like New York, Boston, or Chicago followed suit?

New York’s composting conundrum

Not long ago, New York City briefly had its own in-home composting program. In 2015, then New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio introduced a Zero Waste initiative similar to San Francisco’s. Composting was its cornerstone. Pandemic-related budget cuts forced the city to suspend the service in May 2020. But even before that, the program was anemic, only diverting 43,000 tons of food scraps in 2017 – just five percent of the city’s total food waste.

Theories abound as to what went wrong. One big one has to do with a lack of public outreach. Even the chairman of the city council’s sanitation committee admitted that no one in his own building knew how the system worked. “In my building, we received the brown bins, and some fliers,” he told the New York Times. “I guarantee I’m the only person in my building who knows how to use them.”

Simply convincing residents to change their long-standing garbage habits was another hurdle. Former NYC Sanitation Commissioner Kathryn Garcia told the Times, “The biggest challenge is asking New Yorkers to do something different.” She related a story about how, when the department was handing out brown bins one man didn’t want one. “But we were handing out compost at the same time, and he definitely wanted the compost. We said, ‘We really need your banana peels in order to make this in the future.’” The man took one of the bins, illustrating the importance of education and outreach.

New York re-launched its composting program in August 2021 in neighborhoods where interest was most concentrated, according to Vincent Gragnani, press secretary at the city’s Department of Sanitation. Soon, there will be 100 bins at schools across the city that can be accessed with a smartphone app or a key card. “Within the next two years, every public school in the city will be separating their organic waste for collection,” Gragnani told RTBC. New Sanitation Commissioner Jessica S. Tisch is in the process of reviewing what has and has not worked with the city’s program in the past, but is not ready to share this publicly.

Can California strike ‘black gold’?

Now, inspired by San Francisco’s trailblazing composting success, California is set to enact statewide composting for all. (Only a small handful of states mandate statewide composting). The goal of the law is to reduce the landfilling of compostable materials by 75 percent by 2025, thereby reducing methane emissions on a massive scale. CalRecycle, the department that oversees the state’s recycling and waste reduction programs, estimates about half of the state’s communities had food and yard waste collection programs at the start of 2022.

There are several things the remaining cities and counties around California can do to emulate San Francisco’s success. One is to stay on message. In 2000, when Recology made green bins available to every resident in San Francisco, the response was mixed. “Some people said, ‘Come and take it back.’ Other people embraced it right away,” recalls Reed. “We were doing a lot of outreach and education in promoting the program and why we think it’s important for people to participate.”

For instance, San Franciscans speak over 100 different languages, so Recology opted to put photographs on the green bins (in addition to a few words in English, Spanish, and Chinese), showing what can and can’t be composted. The company also produces a customer newsletter that comes with its bills, filled with articles about the benefits of composting and recycling. In addition, Reed, a former reporter, worked closely with journalists to get stories published early on about restaurants embracing composting and vineyards relying on compost from the city.

But according to Reed, the key to composting success is getting kids on board. “The best way to get adults to compost is to get composting programs running in schools,” he says. Recology donates compost to school gardens, which makes a big impression on children. “Those kids go home and say, ‘Why don’t we compost at home?’ The very next day the dad has a pail on the kitchen counter, and they’re rolling.”

Prior to the pandemic, classrooms would visit the Recology Environmental Learning Center and even take tours of the composting and recycling plants. During Covid, Recology’s programming for students has shifted online. The company leads virtual field trips via Zoom and has produced educational videos and games about composting and recycling for kids from pre-K to high school. There’s even a “Better at the Bin” coloring book.

Finally, Reed says regular and frequent communication with the city is key to the composting program’s success. Every week, Recology staff members meet with a team from the Department of the Environment. “We all have the same goal: to send as little as possible to the landfill,” Reed says. At these meetings, they compare the tonnage that the city is sending to compost versus sending to the landfill, brainstorm ways of getting more residents to compost, and discuss messaging.

One conundrum recently tackled in these meetings was how to encourage more participation in apartment buildings, which have lower rates of composting and recycling, and where 65 percent of San Franciscans live. Their solution: recruit volunteers at these buildings to distribute Recology’s monthly newsletter, as well as encourage composting in neighborly ways, like with composting contests or quizzes. “These are very creative people!” says Reed. “They keep composting part of the conversation.” There are now advocates in 100 buildings around the city.

One of these is Madeleine Trembley, who lives at the Gateway Complex in the city’s Financial District. A year ago, Trembley, who refers to compost reverently as Black Gold, started a newsletter for her 1,255-unit building called Trash Talk. “The newsletter immediately got a lot of peoples’ attention,” Trembley says. “It was educational, practical. We give tips that people can implement easily, understand easily.” As a result of her newsletter and the topics it covered, more young residents have gotten involved in the Board — and one of them is even making video tutorials about composting to share with residents. “It just makes no sense to create more methane gas to stow it away in the landfill. And I think a lot of people realize that.”