This is part three of No Matter Who Wins, a three-part series about positive changes that will likely continue regardless of the outcome of the 2024 US election. Read part one here, and read part two here.

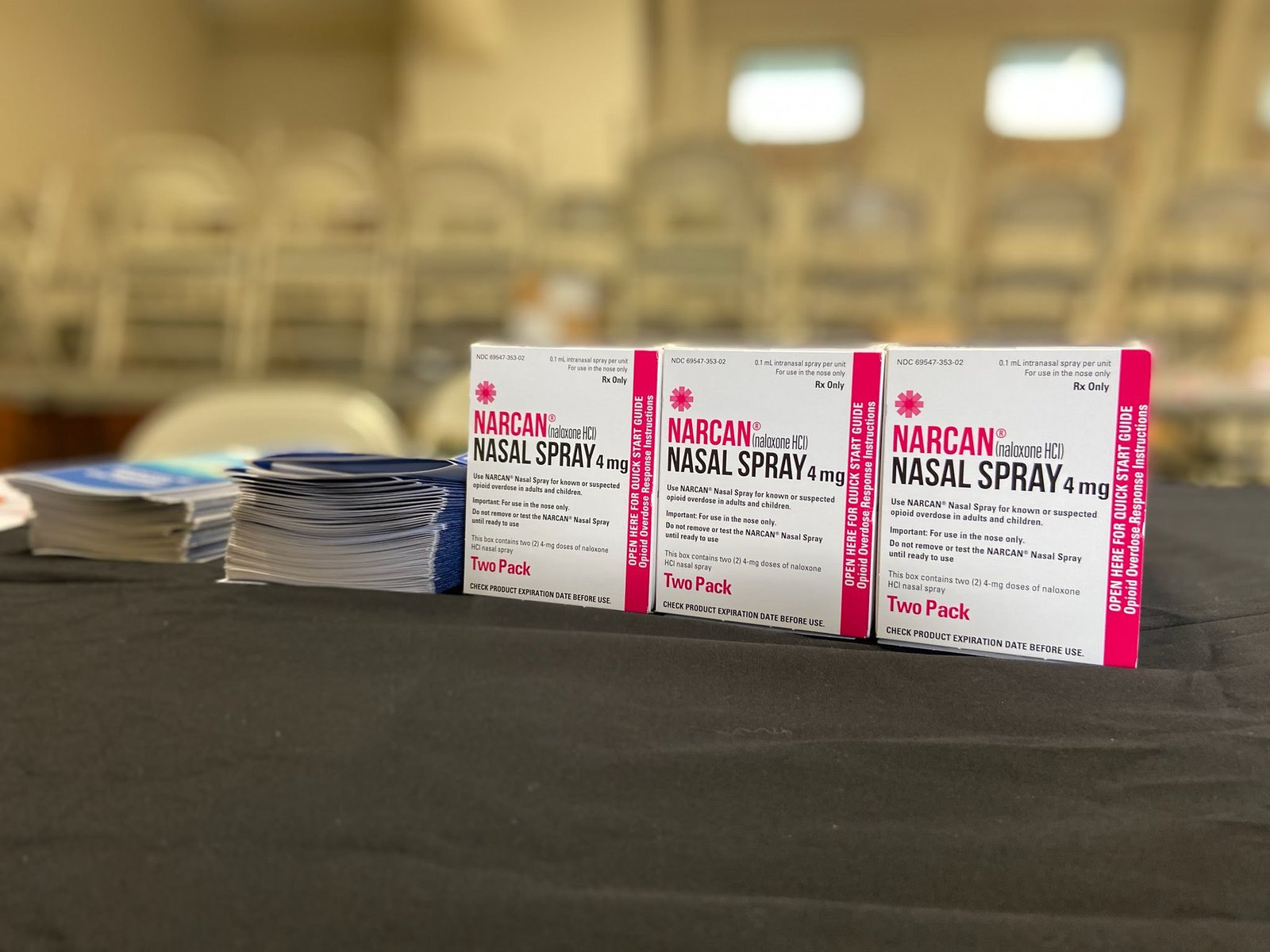

On a college campus in Mississippi this fall, Charlotte Bryant, outreach coordinator for Stand Up Mississippi, taught a group of students how to administer naloxone on someone who may have overdosed on opioids: Check for symptoms of an overdose. Insert the dispenser into a nostril and spray. Hold the device in place for a count of five. Call 911, and keep monitoring the person in case they need CPR.

Bryant had been invited after a member of the student government association had accidentally overdosed. She took what she believed to be Adderall but was actually fentanyl, a powerful synthetic opioid that fueled a rise in overdose fatalities in the US to almost 110,000 in 2022. This student survived, Bryant says, and made it a priority to raise awareness of this life-saving tool among her fellow students.

Bryant and her colleagues at Stand Up Mississippi, part of the state Department of Mental Health, have given similar presentations to law enforcement officers, teachers, in prisons and at churches across Mississippi. Understanding the signs of an overdose, and feeling comfortable in how to use this simple medication, saves lives, she says: “It’s basically like CPR for an opioid overdose.”

Programs like this have ramped up across the country in recent years, and are likely one of the factors that contributed to some rare good news in the opioid epidemic: After rising for nearly half a decade, the number of fatal overdoses appears to be down 10 percent across the country.

Throughout the contentious 2024 US presidential campaign, health issues like reproductive rights and the future of the Affordable Care Act have been lightning rods. But beyond the heated debates, there have been many positive developments with health and medical services in recent years, with support from across the political spectrum. Many of these are equipped to continue, regardless of who moves into the White House in January.

One of the biggest shifts came out of the pandemic. Telehealth was a little-used option before Covid-19’s extended shutdowns forced so much of life online. But even after in-person treatment resumed, telehealth endured, offering new opportunities for medical access.

“There’s really broad consensus among patients, providers, policymakers that it’s generally a good thing and has increased access to services,” says Julia Harris, director of health policy at the Bipartisan Policy Center.

Telehealth is filling in gaps in the health system, including in rural areas, where there are an estimated 30 specialists per 100,000 people, compared with 263 in urban areas. Remote appointments are saving patients long trips and helping people access services that are scarce, like gender-affirming care.

Weighed down by negative news?

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.One major hurdle is broadband access — as of 2021, more than a quarter of rural areas in the US lacked high-speed internet. And policies on some aspects, like prescribing and licensing, are yet to be finalized.

But support for virtual options is strong, and these expanded health services are having real impacts. In the past, sexual assault survivors in rural areas had to take long trips to get medical evaluations because small regional health centers didn’t always have a trained sexual assault nurse examiner, or SANE. Now, through a service called teleSANE, local medical personnel can complete exams under the guidance of a trained examiner, who oversees the process remotely.

Perhaps the biggest development in telehealth is the expansion of mental health treatment.

For young people, especially, virtual treatment is proving to be a good fit. Meeting with a therapist remotely offers practical benefits, like fitting in around school schedules or health needs. But for some teens, it’s a matter of preference. They just feel more comfortable. In 2022, when 75 percent of in-person services had resumed post-pandemic, young people were using virtual mental health services at a rate 23 times higher than before Covid.

There are benefits on the other end of the age spectrum, too. Older adults who live in remote areas have limited options for mental health treatment. With telehealth, they can avoid lengthy, uncomfortable trips to appointments. These virtual services are also reducing the use of antipsychotic medications, which are often prescribed to minimize aggressive behavior among people with dementia.

Beyond telehealth, bolstering mental health services has become a bipartisan issue. According to Harris, finding ways to support youth mental health is of particular concern. Two out of five high school students report feelings of sadness or hopelessness.

In some areas, schools are playing an important role. One Long Island school district, faced with a high number of students coping with grief related to the deaths of loved ones, launched a free wellness center. Mental health professionals offer group and individual therapy services that help children process grief and life transitions. Since the program started, the district has boosted graduation rates to 12 percent above the national average.

Supports are also improving in rural communities. High numbers of suicides among farmers sparked a broad range of responses, from federal funding to expand services in regions that lack mental health professionals, to community-rooted efforts that build relationships and reduce stigma.

Meanwhile, on the opioid crisis, the decline in deaths is a positive step — even if the total number of fatalities remains in the six-digits.

“There’s been a lot of good progress in helping get us past those huge spikes that we were seeing, but a lot of way to go,” says Harris.

People across the political spectrum see the crisis as a priority, and there’s bipartisan support for measures to expand treatment. There are divisions: While left-leaning cities and states have adopted an approach known as “harm reduction,” which aims to help people who use drugs do so more safely, conservatives are skeptical.

But some measures, like the expansion of access to naloxone, have reached across the country. Initiatives like Stand Up Mississippi are not only getting tools like naloxone, fentanyl testing strips and drug disposal kits out into the community; they’re also raising awareness of the realities of opioid addiction and the hope for recovery.