This story was originally published by High Country News.

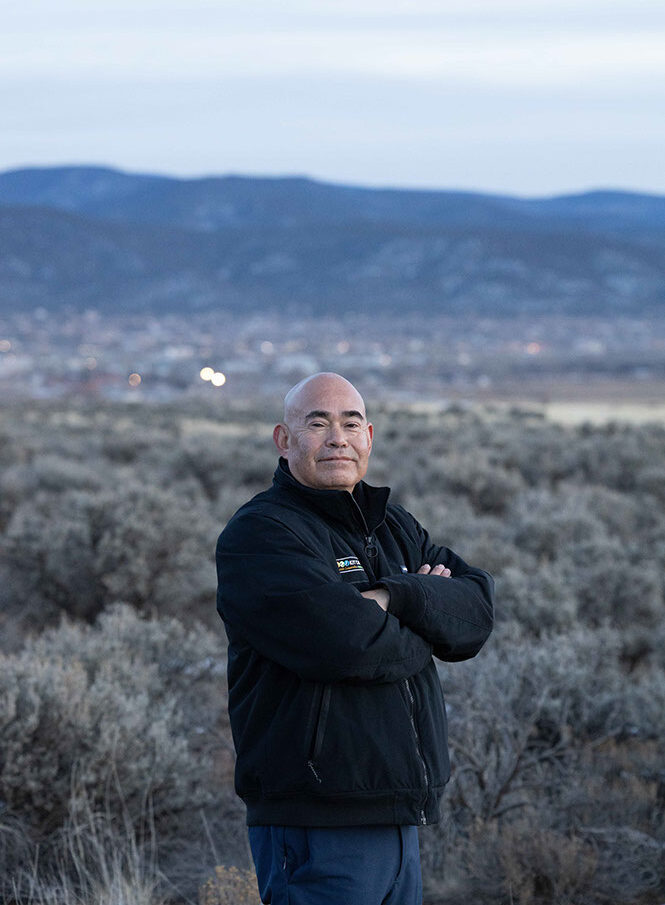

In 2006, Luis Reyes Jr., CEO of Kit Carson Electric Cooperative, an electricity distribution cooperative in northern New Mexico, was in a bind. On one side, clean energy proponents were pushing him to add more renewables. On the other, Kit Carson’s energy supplier, Tri-State Generation and Transmission, was doubling down on coal. Worse, the co-op’s contract with Tri-State — which barred it from producing more than five percent of its own energy — wouldn’t end until 2040.

“That was really the start of the breakup,” Reyes said.

Kit Carson’s ensuing separation from Tri-State, which took nearly a decade, was driven by the persistence of its members. Unlike investor-owned utilities, which are controlled by shareholders, rural distribution co-ops answer to the households and businesses that use the energy.

A product of the New Deal, Kit Carson was founded in 1944 to bring electricity to rural northern New Mexico. Today, there are 832 rural distribution co-ops nationwide.

In general, rural co-ops rely more on coal and have moved more slowly toward decarbonization than large investor-owned utilities. But that’s changing, with Kit Carson leading the charge. Co-op members worried about climate change are leveraging the distinctly democratic governing structures of rural distribution co-ops to encourage decarbonization. Robin Lunt, chief commercial officer at Guzman Energy, Kit Carson’s current energy supplier, called co-ops “a great bellwether” for shifting public opinion.

“They’re much closer to their communities,” she said, “and to their customers, because their customers are their owners.”

But democracy is messy, and change can take years. Lunt praised Reyes’ patience and persistence at Kit Carson, while Reyes credits the committed, vocal co-op members who pushed it to be “good stewards … of the land and water.” Still, the job is far from done, as the co-op continues its struggle to phase out fossil fuels entirely.

Reyes was raised in Taos, in a home powered by Kit Carson. He was with his mother one day when she paid her bill at the co-op office. A manager offered Reyes a job, which he took after graduating from New Mexico State in 1984 with a degree in electrical engineering. A decade later, he became CEO.

The early 2000s found the co-op trying to expand its offerings in rural areas and launch internet services. Tri-State was also trying to grow, and, in 2006, it announced plans to build a large coal plant in Kansas. It also wanted Kit Carson to extend its contract until 2050, adding another decade. It was around this time, Reyes said, that some members started asking “some pretty tough questions,” wondering why the co-op wasn’t investing more in renewables and whether it should extend its Tri-State contract.

Bobby Ortega, a retired community banker who was elected to the board in 2005, said that some board members, himself included, were hesitant to move away from fossil fuels. “When I got on this board, I was more leaning towards coal,” he said. “We were all raised on that kind of mentality (about) how our energy would be derived.”

Most of the board members had open minds, though, Ortega said, and Kit Carson refused to consent to an extension of the contract. The co-op wanted to end its relationship with Tri-State. But legally, the contract was still in force, and Kit Carson needed to find another energy provider before it could leave Tri-State.

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.In the following years, the co-op convened a committee of its members to discuss increasing solar energy usage. Tri-State, however, had set a five percent cap on locally generated electricity. In 2012, a group of Taoseños who shared an interest in renewable energy formed a nonprofit, Renewable Taos, and set a goal of 100 percent renewable energy for the area — a goal that was blocked by the Tri-State cap.

Renewable Taos reached out to Reyes to discuss the issue. As a co-op, Kit Carson needed buy-in across its service area — Taos and the Taos and Picuris pueblos, along with parts of Colfax and Rio Arriba counties — in order to make large-scale changes. But the co-op’s membership was hardly a monolith. “You had the liberals,” Reyes recalled, and the Renewable Taos members worried about climate change. But there had been an influx of “very wealthy but very conservative folks” in the Angel Fire ski area, and some of them were actively skeptical of renewables. Other Kit Carson members, notably those without much disposable income, feared that renewables would increase their monthly expenses.

Renewable Taos began attending Kit Carson’s board meetings with a new goal in mind: moving the entire service area to 100 percent renewable energy if the Tri-State contract was broken. “We didn’t align at all,” Reyes recalled. The board thought Renewable Taos, some of whose members were well-to-do retired scientists, were “kind of telling us dummies what to do,” he said, with a chuckle.

But Reyes and the board found a way to address that tension. “At the end of our first meeting (with Renewable Taos), I suggested to the board, well, if these guys are really going to help us and be critical, let’s give ’em some homework,” he said. The board asked Renewable Taos to visit every municipality Kit Carson served to build support for a joint resolution declaring that all co-op members were committed to fighting climate change.

Jay Levine, one of the original Renewable Taos members, still wonders if that was an attempt to put them off politely. Even so, the group accepted Reyes’ challenge, visiting every municipality in Kit Carson’s service area and answering questions about renewables and energy costs. “We talked to a lot of folks, and I think everywhere we went, they signed on,” he said. The process was aided by the falling cost of solar energy, which began reaching price parity with coal in the mid-2010s.

By 2014, every community in Kit Carson’s service area had signed on to Renewable Taos’ clean energy resolution. Two years later, after the co-op board finally found an alternate energy supplier, it broke its Tri-State contract for $37 million. Thanks to increased control over its power sources, Kit Carson reached an important goal in 2022: Renewable energy now provides 100 percent of the year-round daytime electrical needs of its more than 30,000 members.

Now, other co-ops, notably Delta-Montrose in western Colorado, are following Kit Carson’s lead and leaving Tri-State in the name of clean energy.

Levine, the Renewable Taos member, said that Kit Carson’s long struggle paved the way for other co-ops to leave Tri-State. “That (trend) literally wouldn’t have happened,” he said, “because nobody else would have had the guts to do it.”

The co-op’s achievement — hitting the 100 percent daytime clean energy milestone — is clearly significant, but it also needs to meet a New Mexico mandate that rural co-ops transition entirely to carbon-neutral electricity by 2050. One potential pathway involves a green hydrogen plant that the co-op has explored with the National Renewable Energy Lab, other government partners and the small village of Questa.

Conventional hydrogen production, which uses fossil fuels, contributes to climate change, but so-called green hydrogen can be produced by splitting water atoms with an electrolyzer powered by renewable energy. Proponents think widespread green hydrogen could reduce US carbon dioxide emissions by 16 percent by mid-century. Despite all the investment and hype, however, few green hydrogen projects have broken ground. Still, Kit Carson has beaten the odds before; Reyes recalled that many people doubted that the co-op would ever reach its goal of meeting daytime energy needs with 100 percent renewables.

The Questa plant would be built at a shuttered molybdenum mine, which operated from the 1920s until 2014 and was a major source of both jobs and pollution. In 2005, a Chevron subsidiary, Chevron Mining, acquired Unocal, the mine’s parent company. Today, Chevron manages the remediation of what is now a Superfund site.

At a series of local meetings, water was the top concern for Kit Carson members. A variety of sources could be used to power the proposed plant, including water that Chevron is already pulling from the underground mine, treating, and sending to the Red River as part of its Superfund mitigation. Reyes is optimistic about the hydrogen project, describing it as the next phase of Kit Carson’s clean energy journey. But he noted that the future of the project, and of the co-op as a whole, ultimately lies in the hands of the co-op’s members. “They have been part of that equation the whole time,” he said.