A Ministry for Loneliness might sound like a poignant literary creation from José Saramago, Haruki Murakami or Gabriel García Márquez. But this governmental office is non-fiction — an official response to “one of the greatest public health challenges of our time,” as former U.K. Prime Minister Theresa May put it in 2018 when she launched “the world’s first ministerial lead” to tackle loneliness.

The move was designed to address a widespread problem. Even before the pandemic, a Kaiser Family Foundation survey found that loneliness affected about one in four U.K. adults. The global coronavirus pandemic and its lockdowns have made loneliness even worse, particularly among groups that already suffered from it.

Now, countries around the world are recognizing the public health effects of loneliness, which England’s national strategy defines as what happens “when we have a mismatch between the quantity and quality of social relationships that we have, and those that we want.” Such mismatches, according to the U.S. National Academy of Sciences, are “associated with poor physical and mental health outcomes, including higher rates of mortality, depression and cognitive decline.”

Following the U.K.’s lead is Japan, which announced in February the creation of its own Ministry for Loneliness to coordinate efforts and promote policy across ministries and agencies to address loneliness and isolation. According to a statement from Japan’s Office for Policy on Loneliness and Isolation, the ministry “will act as a kind of control tower for efforts by the government as a whole to provide more appropriate assistance to those who need it.”

A “control tower” for loneliness

Japan’s Health Ministry revealed that 20,919 people died by suicide in 2020, marking “the first year-on-year rise in suicides in more than a decade, with women and children in particular taking their lives at higher rates,” according to one media report. How many of these suicides had loneliness as a contributing factor is unclear. According to Tetsuya Matsubayashi, a professor at Osaka University who studies suicide prevention, “Loneliness is certainly an important determinant of suicidal risk, but we need more evidence to say it is more important than other major determinants, such as economic difficulties and family matters.”

“The government,” observes Matsubayashi, “needs to continue to collect more evidence to develop an effective prevention strategy.”

To this end, Japan’s new ministry has established a task force that will engage “in practical study toward future efforts” on loneliness and isolation. Following the creation of the loneliness initiative, an emergency forum was held in February to gather local input from organizations that assist efforts to combat loneliness. The government also held a coordination conference between ministries and allocated emergency funds of approximately six billion yen (USD$54.6 million) to nonprofits.

These steps represent a pivotal change in mindset in a country where social isolation has long been considered an issue to be dealt with personally. “In Japan, solitude can be seen as a virtue and something you are ultimately responsible for addressing yourself,” Junko Okamoto, author of Japanese Old Men: The Loneliest People in the World, told Nikkei Asia. “The government needs to swiftly conduct foundational research and craft strategy based on scientific evidence.”

England’s experience

In its endeavor to craft such a strategy, Japan has, to some degree, borrowed from the U.K.’s approach. On December 7, 2017, a report from the British government’s Jo Cox Commission on Loneliness recommended that officials there implement actions and policies to alleviate loneliness and social isolation, including the appointment of a ministerial lead on the issue. The position was created the following month, a clear acknowledgment from the government that, through its strategy, it had a role to play in reducing loneliness.

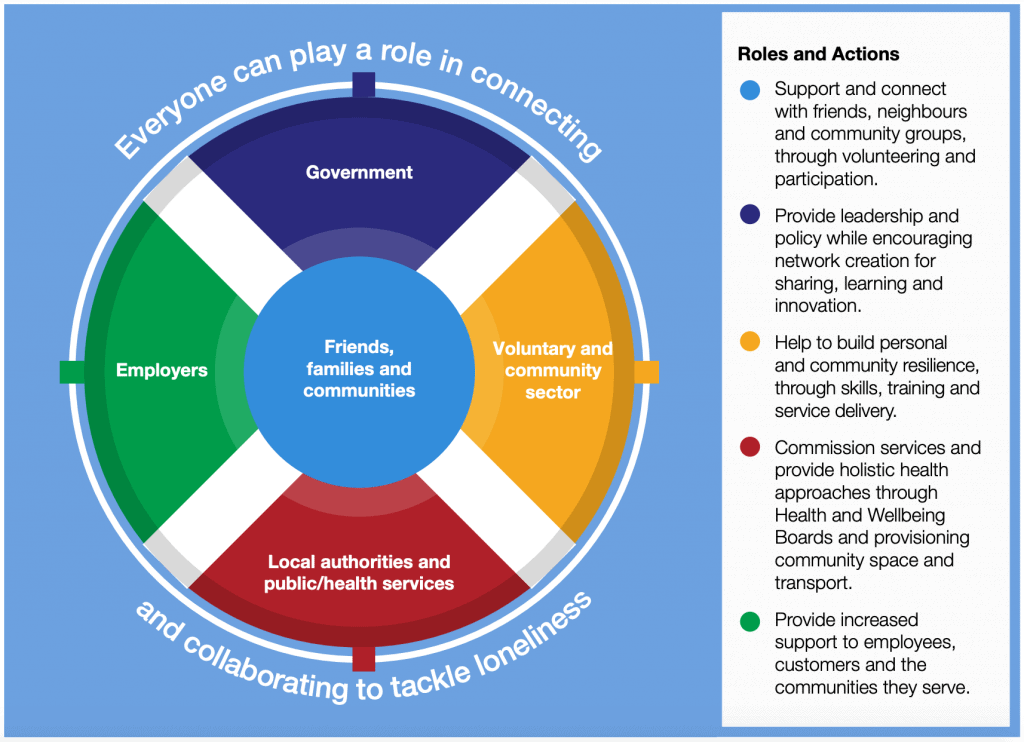

This strategy, titled A Connected Society and unveiled in 2018, is an ambitious cross-departmental set of over 50 commitments laying the structure for long-term work on loneliness and changing how public services are viewed. It has three overarching goals: developing a national conversation on loneliness to reduce stigma, building evidence on loneliness, and driving a governmental shift so that relationships and loneliness are considered in policymaking.

In England, where 45 percent of adults experience some degree of loneliness, the issue is both social and economic. A 2017 report by the New Economics Foundation found that loneliness costs U.K. employers £2.5 billion (USD$3.4 billion) per year in employee health problems, productivity losses and staff turnover.

To support organizations working to combat loneliness, the government announced £20 million (USD$27.5 million) in funding, including £11 million in grants to 126 organizations. It also made social prescribing one of its strategy’s central commitments, funding the recruitment of 1,000 additional “social prescribing link workers” within primary care networks by April 2021.

Social prescribing link workers — also known as community connectors, well being advisors, community navigators and health advisors — support non-clinical needs in a wide range of people, including those who feel lonely, according to England’s National Health Service (NHS). They are recruited for their listening skills and empathy, and may connect people in need to community groups and services for practical and emotional support.

In another of the strategy’s pledges, Royal Mail postal workers were tasked with checking in on older people as part of their delivery rounds and referring those who reported feeling lonely to appropriate support. An evaluation of this program by the Loneliness Action Group, jointly chaired by the British Red Cross and the Co-op Foundation, showed that “three quarters of people valued visits by postal workers” and “trial partners were exploring ways to scale-up the service.”

The government’s strategy also included collecting and tracking evidence to inform future policy, prompting the Office of National Statistics (ONS) to develop national standards for measuring and tracking loneliness — for instance, by surveying citizens with standardized questions on the topic, with variations on wording for children and detailed guidance on how to administer the surveys.

Still, quantifying progress on reducing loneliness can be difficult. One government campaign launched in 2019 called “Let’s Talk Loneliness” aimed to challenge the stigma surrounding loneliness by encouraging the importance of talking about it. The campaign was advertised across 20 big digital screens around the country and included a toolkit for organizations that help those experiencing loneliness. But according to the Loneliness Action Group, “little is known” about whether this or other types of public campaigns are effective in tackling loneliness. The report recommends measuring the impact of this campaign: “Using this data to inform future work will be vital.”

The Loneliness Action Group produced a one-year progress report on England’s strategy and found that while “progress has been made” in setting up the policy structures to drive action, there is “still more to do to secure tangible change in the levels of loneliness across the country.”

A tricky issue to tackle

The All-Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) on Loneliness, established in 2018 to raise parliament’s awareness of loneliness, recently published a report echoing the Loneliness Action Group’s call for consolidating and building on what was learned from the pilots in England’s loneliness strategy, such as the Royal Mail initiative.

“Most of these pilots have now been completed, but best practice has often not been shared or spread,” says Olivia Field, head of health and resilience policy at the British Red Cross.

Weighed down by negative news?

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.Progress across departments has been uneven. For instance, transport and housing require more concrete action on loneliness, according to the Loneliness Action Group’s report. The APPG notes that both of these areas play an important role in supporting people’s ability to connect, calling on the government “to ‘loneliness-proof’ all new transport and housing developments.”

“During inquiry,” Field says, “the APPG heard how poorly designed or unsuitable housing environments can make it harder for people to host visitors as well as get out and about.” In other cases, says the APPG report, “a lack of affordable and suitable housing forced them to move away from the communities with which they were most connected. For others, poorly repaired or cramped housing conditions made it hard to maintain social connections.”

When designing new housing developments and transport, says Field, groups at risk of loneliness and exclusion should be consulted. “Simple things like putting in more benches, putting seating in apartment block corridors, communal gardens and warm lighting can help neighborhoods connect.” Survey respondents highlighted the role of lobbies, shared outdoor spaces and lounges, access to the nearest bus stop, and ensuring all residents have the same access — to play areas, for instance — to foster connection between neighbors.

Inequities, inevitably, play a role. “The inequalities exposed and exacerbated during the pandemic show the need to do more to support areas with higher levels of deprivation and limited community and social infrastructure,” says Field. “It has also further exposed the link between financial hardship, mental health and loneliness.”

One component to fixing this, as the government’s strategy envisioned, is the roll-out, currently underway, of social prescribing as a universal offer in health care by 2023. Field says the British Red Cross has seen first-hand how effective social prescribing can be in tackling loneliness. The organization’s evaluation “found this service helped two thirds of the people it supported to feel less lonely and 76 percent saw an improvement in their well being,” she says.

Taken as a whole, England’s strategy reflects a growing consensus that, while loneliness may be something that happens to an individual, the remedies for it can be supported by policy and government programs. As the APPG report puts it: “While we know that it’s locally, in our own communities, that people make friends and find companionship, national leadership is vital in setting the strategic direction, providing the impetus for action, and funding the activities and infrastructure needed to connect.”