When Captain Emada Tingirides and Sergeant Christian Zuniga arrive at Nickerson Gardens, a public housing development in Watts, a Hispanic family carries a bleeding toddler to them. A stray dog bit the child in the cheek. As Zuniga comforts the little girl, Tingirides chats up the shy older daughter and gives the mother a phone number for a free family counselor. “Our main job is to keep the community safe,” Tingirides says. “But this can also mean helping a family get groceries or sending a youth to counseling, because these are aspects where crime can develop. It is a holistic approach.”

Tingirides, 50, is only the second Black female officer in Los Angeles to reach the position of Deputy Chief. Since September 1, 2020, she has been in charge of the Department’s new Community Safety Partnership Bureau (CSP). “It’s about trust,” Tingirides says when asked to describe CSP. “The community has to hold law enforcement accountable, and law enforcement has to hold communities accountable. We ask the communities what they expect from us, and we take their goals seriously.”

CSP represents a major shift in L.A.’s notoriously hardline approach to policing. (The department faces more than 2,000 lawsuits from activists involved in last summer’s racial justice protests.) But there’s reason to believe it could stick — independent studies have shown that the CSP has increased trust in police, reduced violent crime and saved the city millions of dollars.

Now, Tingirides is working to expand the program from its current ten neighborhoods to more of Los Angeles — all while trying to sustain the inroads it has made with the Black and brown communities it has touched.

“My son is 20 years old and Black,” says Tingirides. “I have to have difficult conversations with him about the police in this country. There are these incidents we all need to own. I know both sides of the debate.”

Soccer tournaments and ‘Donuts for Dads’

Nickerson Gardens was the site of violent turf wars between the Bloods and the Crips in the ‘80s and early ‘90s. “Right where we stand, between the gym and the parking lot, the deadliest shootings happened,” Sergeant Zuniga recalls. Today, children play outside. No gang graffiti is visible. Tingirides and Zuniga stroll around on foot, waving. Most residents wave back. “Nobody can stop the war but us,” is written on the walls of the community house.

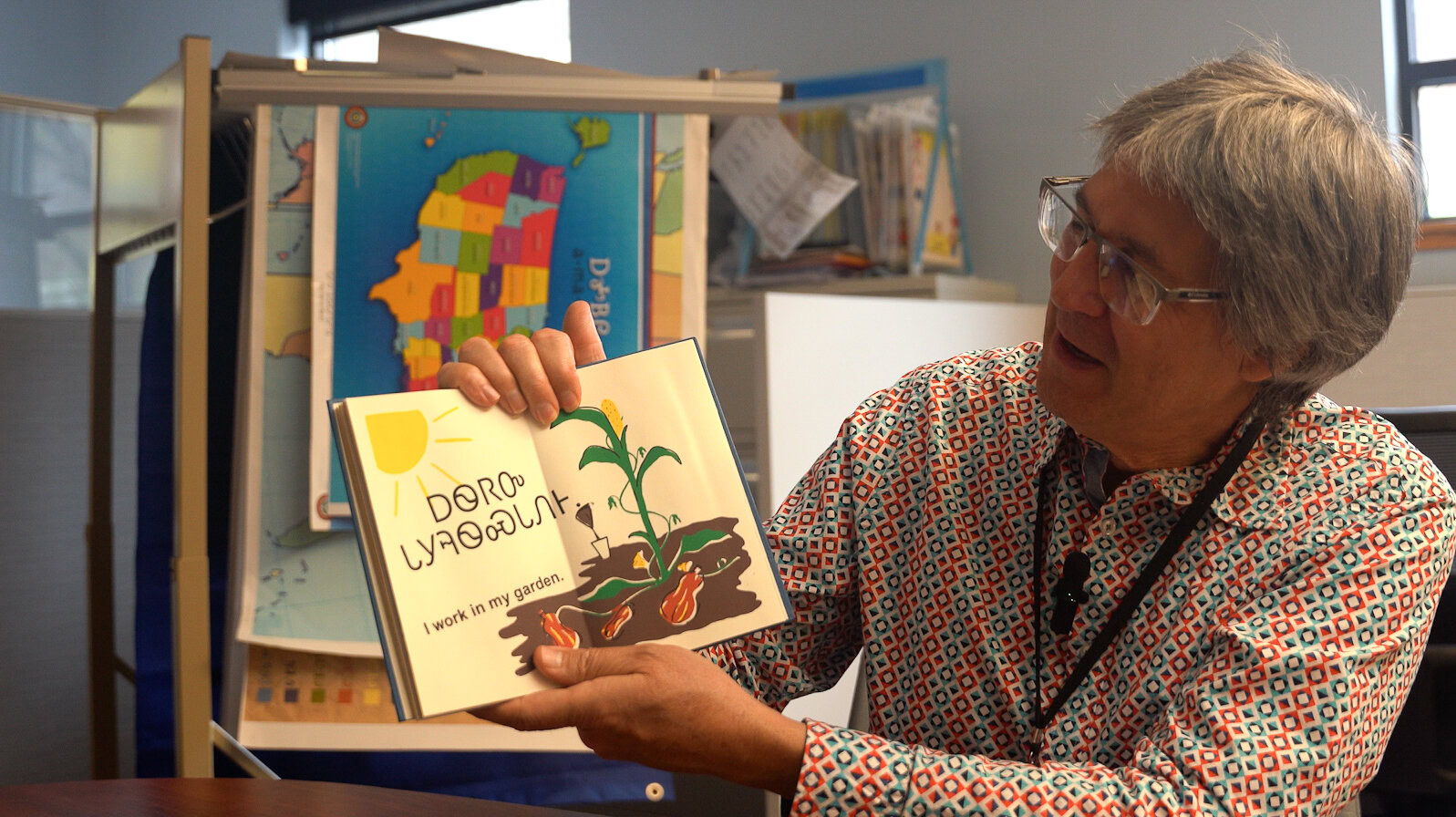

Emada Tingirides knows Watts like her home because it is her home. She grew up in the neighborhood, the daughter of a single mother and the grandchild of a policeman. Long before the LAPD created its first official CSP-program in 2011, she visited elementary schools in Watts to read to the kids. She remembers how afraid the children were of her — it took almost a year before they leaned in for hugs. Now, residents and colleagues playfully call her “Captain T” or “Emada,” a sign of endearment.

This is the mindset shift the Partnership aims for. Under the CSP concept, police officers are stationed in an area for at least five years. They become part of the community, attend neighborhood meetings, organize soccer tournaments, hand out “Donuts for Dads,” and “Muffins for Moms.” They work closely with gang intervention workers, social workers, non-profits and, most important, neighborhood residents. “I thought all cops were bad,” a nine-year old boy admits. But now, he says, he loves Community Officer Jeff Joyce, who started “Nicks Kids,” a soccer club for youths. “Our methods are unconventional, and we are adaptable,” Tingirides says. “Each neighborhood is different.”

Weighed down by negative news?

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.Each of the 100 Partnership officers undergoes training by the Urban Peace Institute (UPI). Human rights lawyer Conny Rice (a second cousin of Condoleezza Rice, the former secretary of state) founded the non-profit UPI to advance non-traditional policing, and has personally trained dozens of officers. “The first thing I tell these cops is that you are not in the arrest business, you are in the trust business,” she told NPR.

Rice and Tingerides have been working together to combine public safety, community outreach and youth programs for the last 12 years. The Peace Institute trains Tingerides’ officers in de-escalation, non-confrontational communication and restorative justice. Mainly, it gets the officers and residents to sit at the same table. “What hits them the most is the emotional connection, learning about the traumas in the community,” Tingirides says.

In March 2020, UCLA published an extensive study analyzing the Partnership’s work, focusing on the housing developments where it was originally implemented, including Nickerson Gardens. It concluded that the program increased trust in police and prevented nearly 20 violent crimes per housing development per year. It also attributed savings of $14.4 million to its presence in the two Watts housing projects, Nickerson Gardens and Jordan Downs. Counting the intangible cost savings of less violence, the analysts concluded the Partnership created more than $90.3 million in overall savings per project. The “war against gangs” over 30 years, by contrast, cost more than $25 billion in Los Angeles and was extremely ineffective, according to the UCLA study. (The study was partially funded by the Ballmer Group, which also supports the Partnership, but UCLA researchers assert that they are independent.)

The Mayor’s Office claims that as a result of the gang intervention programs, including CSP, violent crime in Watts has decreased more than 70 percent in the housing developments, and youth arrests have been cut in half. Violence began rising in Los Angeles in 2014, but it kept decreasing in Partnership neighborhoods.

The difference, however, only started showing after three years of Partnership presence. This is how long it took to establish enough trust for the program to work. “We have implemented the program in ten neighborhoods,” says UPI’s executive director Fernando Rejón, “so we know what it takes to take it citywide. It won’t be easy or quick or make politicians look good. It is very risky, takes time and a lot of commitment.”

Still, not everyone wants the Partnership to expand. Baba Akili, a longtime local Black Lives Matter campaigner against police abuses, said the program misuses the word “community” and would do nothing to stop abuse. “Stop using our terms,” he said during the public hearing on the Partnership. He called community policing “over-policing with a smile.”

Sergeant Zuniga used to be skeptical, too. He was “a typical street cop” fighting gangs the traditional way. “We got a lot of drugs and weapons off the street,” he says, “but we also left a lot of damage in our wake.” He admits he only applied for the CSP position ten years ago because it meant a promotion. Today, however, he is convinced that violence cannot be “arrested off the streets.”

“I’m not under the illusion we can abolish crime forever, but the question is: Can police play a role in which we solve crime together with the residents, and even intervene in the life of people before they resort to crime?”

When two young Black boys race their motorized mini-bikes by us on the sidewalk, Zuniga stops one with a friendly, “Hey, bro!” Street cop Zuniga would have confiscated the souped-up mopeds. “It would cost the parents $400 to get them back. That’s money they don’t have. What would that accomplish?” Instead, he tells the boy to wear a helmet and to look left-right-left before crossing the street again. The tot lets the engine rev and dashes away with a relieved grin. The next time he comes around, he’s wearing a helmet.

The relationship with the residents remains fragile. Zuniga remembers a five-year-old boy who was run over by a car. Zuniga, who administered first aid, watched the boy die in his arms, but the family insisted that he and his colleagues attend the funeral. Zuniga was one of the pallbearers. At other times, however, he has misjudged situations and found himself encircled by gang members.

“It took decades to create these conflicts, and it will take decades to solve them,” he reasons. “It is possible that we earn the real fruits from this work in 40 years, when we’re long retired.”