Not long ago, news stories about LGBT health were rarely something to celebrate. AIDS was endemic, and systemic discrimination had caused a full-blown mental health crisis. As for transgender people? Their health needs were either treated with disdain or simply ignored.

The picture may not be perfect today, but it’s a lot prettier than it was.

It was a pivotal decade in many ways. Cities from New York to Sydney got on a glide path toward ending HIV transmission. A pill called PrEP offered, in essence, an HIV vaccine you take on a daily basis. Social achievements like same-sex marriage dramatically improved gay and lesbian mental health. And the medical establishment finally began to acknowledge transgender health needs. There’s still a ways to go, but all in all, it’s been a good ten years. Here are some highlights.

In many places, HIV transmission rates hit historic lows

New HIV infections fell precipitously in the last 10 years, a decline driven, in many places, by men who have sex with men.

For instance, in just the past two years, incidents of new HIV infections among gay men in Britain fell by an astonishing 55 percent. In New York, new diagnoses occur half as frequently as they did a decade ago. In San Francisco, they dropped by 62 percent. And a decade that started with a headline declaring “HIV Spread ‘Out of Control’ Among French Gay Men” ended with Paris reporting infections down in gay men by 28 percent.

Many parts of Africa and Asia also registered declines in the spread of HIV, though in those regions the disease isn’t as concentrated among gay men.

Perhaps the most exciting progress was made in Australia, a country that appears to be on track to eradicate transmission of HIV entirely within the next decade. In Western Australia today, HIV transmission rates among gay men are lower than they are for straight men, having crashed by 51 percent this year alone.

We got the next best thing to an HIV vaccine

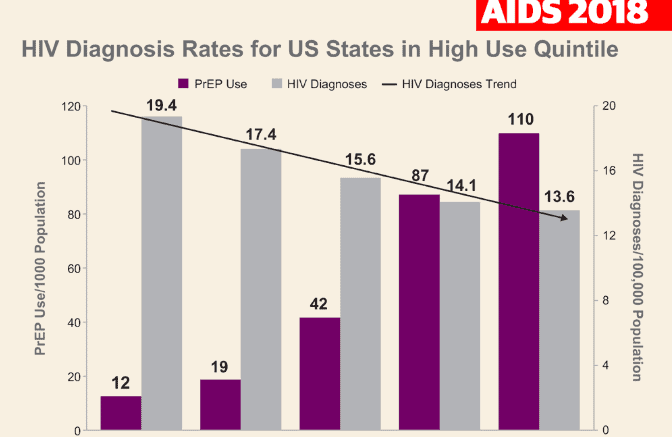

Credit for some of the progress in these declines is due to the rising popularity of PrEP, the once-a-day pill that’s highly effective at preventing the transmission of HIV. With more gay men protecting themselves, this double-take headline appeared in the New York Times on October 2, 2019: “New York Says End of AIDS Epidemic is Near.”

PrEP, or pre-exposure prophylaxis, dramatically decreases transmission risk when taken correctly, and as its availability has spread it has become a game-changer. By 2019, about 40 countries had made PrEP part of their official response to HIV, a 40 percent increase from three years earlier, with the biggest gains in Europe and Africa.

PrEP’s big drawback is the cost — the list price of Truvada, PrEP’s brand-name drug, is $2,000 per month. But many countries have moved to make it more accessible despite the price tag. In 2016, the only country in Europe where PrEP was reimbursed on a national level was France — today, the national health systems of 14 European countries reimburse for PrEP. Even the ramshackle U.S. health care system is moving to make PrEP free for high-risk populations, which includes gay men who have multiple partners, as part of a national plan to eradicate HIV by 2030.

Transgender health finally got some attention

The field of transgender health care was sparse a decade ago, to say the least. Now, it’s “growing rapidly,” though there’s still a long way to go.

One of the early landmarks in the U.S. came in 2014, when a government appeals board ruled that Medicare, the national health provider for older Americans, must cover gender-reassignment surgery. Today, many U.S. states still fail to provide publicly funded gender-reassignment surgery, but others have begun to, including states that voted for Donald Trump in the last election. Perhaps not surprisingly, higher education is ahead of the curve — several universities launched clinics aimed at providing health care specifically geared to the needs of transgender people.

Other countries are further along. Some form of gender-reassignment surgery is now publicly covered in all of Canada’s provinces, with British Columbia dedicating an entire segment of its health service to transgender care. And this year, South Africa opened its first facility specifically devoted to transgender health, a groundbreaking move from the only country to include gay rights in its constitution.

It will take a lot more work before health care parity for transgender individuals is achieved, but there’s reason to believe the next decade will build on the gains of the one ending now.

As social acceptance improved, so did mental health

It’s been scientifically proven that sexual minorities living in discriminatory places die earlier than those residing in open-minded communities. So it’s no surprise that greater global acceptance and the granting of basic rights have led to improved LGBT mental health outcomes over the past ten years.

For instance, a 2019 study found that suicide rates among gays in Sweden and Denmark have fallen significantly since the advent of same-sex marriage rights in those countries. In the U.S., similar declines were found among LGBT teens after same-sex marriage was nationally legalized in 2015.

Stricter laws against bullying have helped, too. Over the past decade, the number of U.S. states that include LGBT youth in their anti-bullying laws rose to 20. In those states, studies have shown that fewer gay youth attempted suicide. And in a move that should have happened decades ago, the American Medical Association finally announced its official support for banning conversion therapy, a sadistic practice that wreaks havoc on LGBT youth mental health.

Some of the decade’s most unexpected mental health gains impacted transgender people. This year, the World Health Organization finally removed “transgender” from its global manual of mental health diagnoses. And a 2019 study confirmed that transgender people who undergo sex-reassignment surgery experience less anxiety, depression and suicidal thoughts.

Besides helping drive transmission rates down to historic lows, PrEP is also having a positive effect on gay men’s mental health. Several quantitative studies have shown that the drug’s availability has decreased anxiety among men who have sex with men.

The medical establishment got less squeamish

These days, it’s often the students pushing for medical schools to improve their approach to LGBT health. At the behest of the student body, Harvard Medical School recently launched a three-year plan to identify ways to improve instruction on sexual minority health. And after lobbying by a group of students, New York Medical College increased the number of hours of LGBT-focused instruction it offers from one-and-a-half to seven.

But these students are preaching to the choir. As it turns out, the number of medical professionals who have a problem with treating LGBT patients may be wildly overstated. When the Trump administration tried to make a rule giving medical providers a religious exemption from treating gay patients, citing the large number of doctors and nurses who feel uncomfortable doing so, a federal judge rebuffed them. Why? After scrutinizing the government’s evidence, the court found that only six percent of the “religious objections” had anything to do with the patients’ sexuality — most were objections to the treatments themselves.

And speaking of cures, this decade France, the U.K. and the U.S. relaxed restrictions on gay men donating blood, taking long-overdue baby steps toward ending a rule considered archaic by many health professionals. Now, LGBT people who are living longer, healthier lives can finally help their straight counterparts do the same.