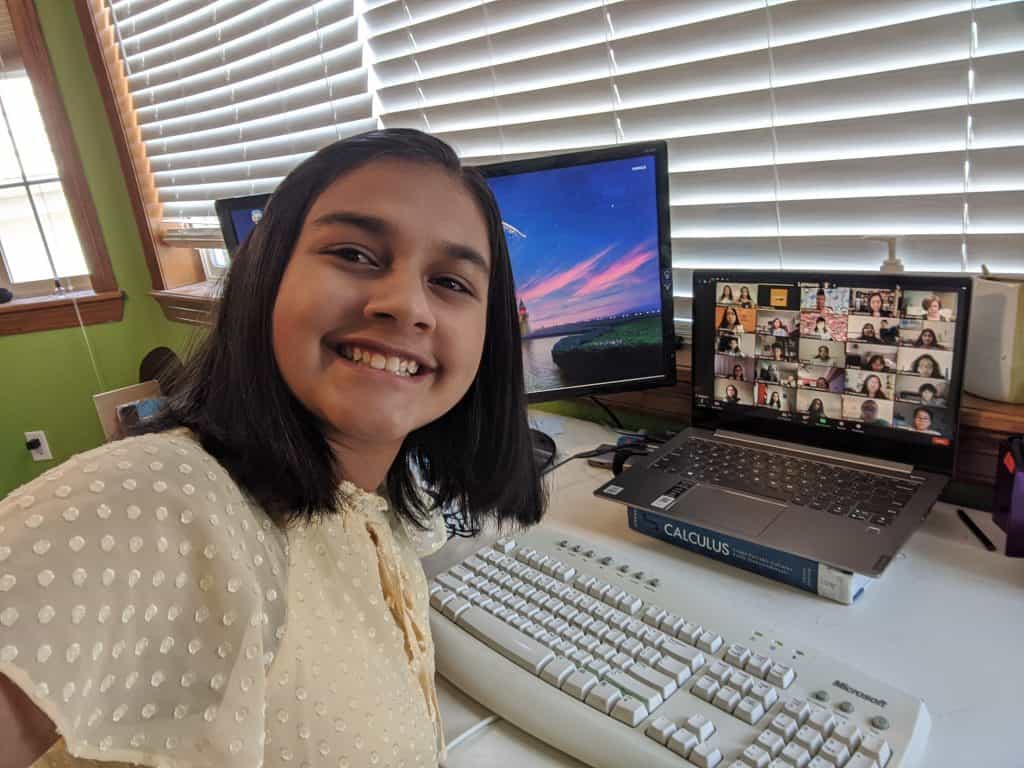

Motivated by the water contamination crisis in Flint, Michigan, Gitanjali Rao was only ten years old when she created her first invention, a now patented lead test for water. For this, Rao, now 15, was named America’s Top Young Scientist of 2017 and TIME Magazine’s first-ever “Kid of the Year” in 2020.

Not one to rest on her laurels, she has since invented an app to fight cyberbullying and an early detection kit for opioid addiction. But today, her greatest passion is getting more people like herself — young, female, people of color — involved in science. RTBC spoke with Rao from Lone Tree, Colorado, where she lives with her parents and younger brother, about the unique contribution her generation can offer, how science can catalyze social change and creating a platform for other young innovators.

You just published a book this spring, A Young Innovator’s Guide to STEM: 5 Steps to Problem Solving for Students, Educators, and Parents. Specifically, how can we get more young people into STEM, especially more young women and people of color?

The first step is introducing young people to more role models. Most scientists don’t look like me. Seeing people who look like you in the field and on the news is one of the most empowering experiences. Science and technology don’t just revolve around robotics and coding, but that’s how it has been portrayed. That can scare people away. I like to present STEM as a means to solve problems, using science and technology as a catalyst for social change rather than just as raw skills.

Do you have role models that inspired you to get into STEM?

My parents are both IT engineers and work in a different field than I do, but they have been my biggest supporters and are my biggest role models. One of the people who first got me interested in STEM is my second-grade teacher. Out of nowhere, she told me I was going to change the world someday, and that stuck with me. Little things like that empower me on a daily basis.

Even now, I do tend to get comments about how I don’t look like your typical scientist. Or, ‘“You’re smart for a girl.”’ When it comes to innovation, a lot of times you’re expected to act or look a certain way. The biggest thing I’ve learned is to recognize that no one defines what I do, except for myself.

When did you first realize you had an interest in science?

When I was four, my uncle got me this earth science kit instead of the Barbie Dreamhouse I wanted. I complained about it for days, but I decided to open the kit and play with it. That was a great starting point. From a very young age, my parents exposed me to lots of ideas. Everything. I did everything. Ice skating. Hang gliding. Fencing. Baking. Playing the piano. I went to flight school. I was trying out things every single day. We had this deal: If I wanted to quit something I could the next day, but I had to go to one practice, one class, or one lesson. I didn’t recognize it at the time, but what that risk-taking did is that I was able to choose my own path and have that path fostered for me.

Did your parents set any limits?

I wanted to invent a chair that sinks into the ground to save space, but my mom wouldn’t let me drill a hole into the floor. So that didn’t work out.

You’re all about finding solutions to pressing problems, just like Reasons to be Cheerful. What are the problems you’re personally most passionate about solving?

The biggest ones are definitely, number one, the contamination of our natural resources. Second, education opportunities, creating equality. Third, the spread of diseases and pandemics. I am working toward finding solutions for these three things in the next couple of years, but obviously, it takes time, effort and people.

Well, you already put in the effort with the first issue, contamination. When you were ten years old, you heard about the water contamination crisis in Flint, Michigan, and with just a cardboard box and a couple of drawings in the beginning, you developed Tethys, a lead test that resulted in you winning the 3M Young Scientist competition in 2017, arguably the most renowned science competition for kids in America. How did you achieve this?

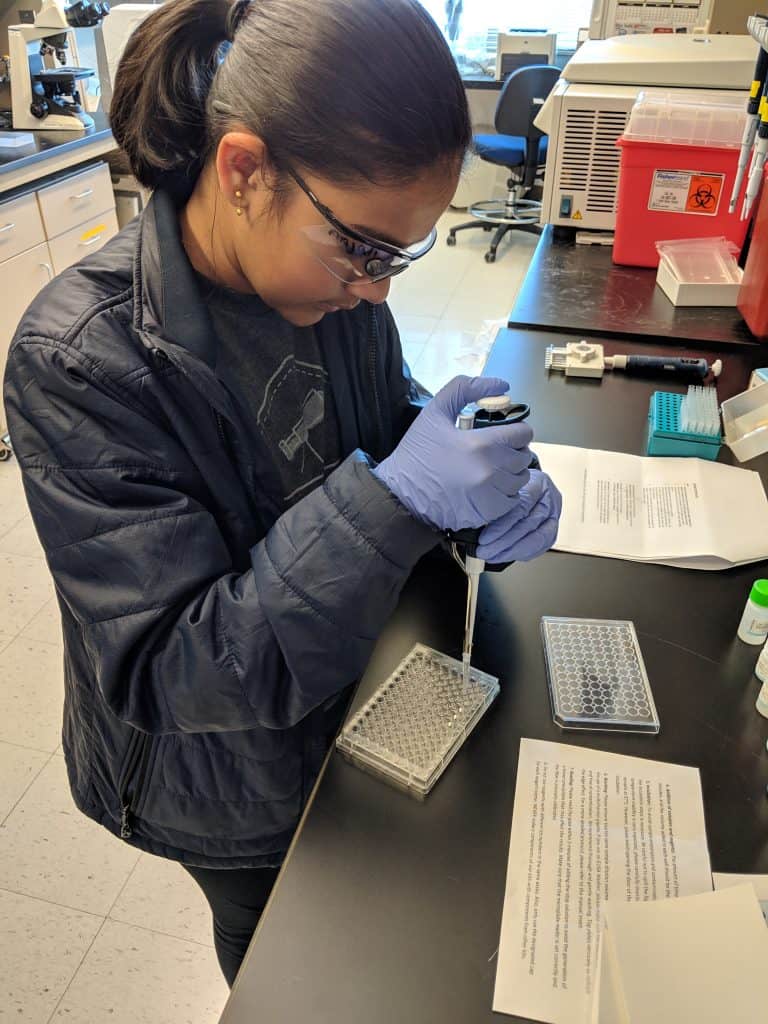

I found it absolutely appalling to see how many kids my age are drinking poison every single day that causes lifelong damage to their mental capacity, their organs and their normal growth. I was also interested to see the impact carbon nanotube sensor technology has. It was already used to detect hazardous gases in the air, and I wanted to create a water-soluble version of it.

Hang on, how did you know what carbon nanotube sensors are at ten years old? I had to look that up.

I was just reading through MIT’s Tech Review, seeing stuff that had already popped up on my radar and recognizing that it could be easily used and shifted over for multiple uses. Tethys is a fully patented device, but it is not currently available for people to start using yet. I’m working with a variety of organizations such as Intel to help with field testing and mass production. Hopefully, in the next couple of years, people can start using it.

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.The idea is that it’s something that anybody could use, like a resident of Flint could use it to test their water, right? You don’t need to be a scientist or have a lab to use it.

Exactly.

How many inventions have you created?

Seven to eight, depending on if you want to count the ones that are not fully developed yet. I’m currently working very closely with UNICEF on Kindly, my app against cyberbullying.

What sparked your interest in that? Have you experienced any bullying?

Not personally, but I recognize it as an issue as someone who’s moved to seven different schools in the past 11 years because of my parents’ jobs. Every new place is something you have to adapt to, with a new set of people. But bullying is an issue that shouldn’t even exist in the first place.

How does the app work?

The best way to describe it is “the spellcheck of bullying.” It looks at the latest terms, emojis, slangs, whatever, and basically categorizes them into various grades of intensity, what may be considered bullying or insults or “nice words.” The application itself is pre-programmed to take further action and send a message. It creates a learning experience out of every bullying situation, with a non-punitive approach.

You’re also creating a network to bring other people who look like you into the field of STEM. How do you envision this?

Three to four times a week, I’m running innovation workshops for students across the world. I have impacted about 50,000 students today across 26 countries and five continents. The goal is to make these innovation workshops self-sustaining beyond me to help students come up with an idea. But we do not stop at the ideation phase; I also mentor them on the execution, allowing their ideas to go from just a concept to out in the real world.

How?

That support needs to come from organizations in the workplace, being willing to bring students in and making internships about more than coffee and copies. Because, believe it or not, youth play a part in the real world. We just need to take advantage of the latest work Gen Z is doing. We might hear about it on the news, but we don’t do anything about their ideas.

What kind of ideas have come out of your workshops that you think have big potential?

One of my favorite ideas is from a kid in Wyoming who came up with this app similar to Pokemon Go, which allows you to collect litter. In the beginning he hated coding, but then he programmed it all by himself. It’s incredible to see how these students really recognize their potential after they recognize that science isn’t as intimidating as it seems in the real world. We just need to present it in a way that people want to engage with it. And that’s what I aim to do.

One of your main interests is opening science access for people who have fewer resources. What do you think schools can do to get more young people interested in science?

K-12 education should explicitly teach ideation and problem solving. We shouldn’t just focus on getting an A in a math class, but getting an A in life. Innovation and problem solving should be introduced at a young age, as an everyday part of our life. And I think that it’s completely possible.

What advice do you have for other kids who want to innovate solutions?

Don’t be afraid to take risks. And don’t be afraid to take that first step. Sometimes taking that first step is all you need to make a difference in society. And remember, the worst answer you’re going to get is no. What’s the worst thing that’s going to happen? It is that you fail. There’s no one stopping you but yourself.