Waterline is an ongoing series that explores the solutions making rivers, waterways and ocean food chains healthier. It is funded by a grant from the Walton Family Foundation.

Looking out along Old Maricopa Road — the state highway that cuts 17 miles north-south through the Gila River Indian Community reservation, just south of Phoenix — David DeJong saw barren land, fallow fields baking under the Arizona sun. It was the 1970s, and DeJong, then a teenager, was on one of his regular drives through the Gila River community from his hometown of Mesa to work on a family farm in Maricopa.

“It was obvious to me that a lot of this land had been farmed, and I wanted to know why it wasn’t being farmed anymore,” says DeJong. “Something had happened here.”

Today, the view from Old Maricopa Road, now State Highway 347, is greener than it was half a century ago. The Gila River Indian Community (GRIC) has been working to bring agriculture — and its lifeblood, water — back to its territory for 150 years. And in their fight, which has spanned federal courtrooms and irrigation canals, the community has found an unlikely and increasingly important tool: wastewater.

Since 2004, GRIC has taken part in a novel water exchange program with two of its neighboring cities, allowing it to swap part of its legally enshrined allotment of Colorado River water for an even larger sum of triple-treated agricultural-grade reclaimed wastewater. In an increasingly water-scarce West, the GRIC water exchange is a model of how residential and agricultural needs can be aligned to create a stable, sustainable and sanitary water supply that connects farms to tables — and back again.

The Gila River Indian Community reservation is home to some 11,000 members of the Akimel O’odham (Pima) tribe and roughly 1,000 members of the Pee Posh (Maricopa) tribe, who live primarily in a small colony nestled in the reservation’s northwest corner. Pima, in the Akimel O’odham language, means “river people,” and the tribe’s history — like its name — is inseparable from its water.

Fed by mountain springs and snowmelt, the Gila River begins in New Mexico’s Elk Mountains and flows west through Arizona to the California-Mexico border, where it joins the Colorado River. Or, it did once. Damming, diversions, climate change and prolonged drought threaten the very existence of the Gila, which, in 2019, was named America’s most endangered river by American Rivers, a nonprofit environmental advocacy group.

In recent years, the Gila has been reduced to a trickle less than halfway into its 649-mile journey. By the time it reaches its eponymous reservation, downriver of both the Ashurt-Hayden and Florence dams, the Gila is “pretty desolate,” says DeJong. He’s now 61 — and 40 years into his lifelong project of studying, writing about and working for the GRIC. “Sometimes the river flows for a few days, maybe for a couple of weeks. Sometimes it doesn’t flow at all in the course of a year,” he says. A historian of American Indian policy by training, DeJong has worked for the Gila River community since 1992, and since 2006 has served as the director of the Pima-Maricopa Irrigation Project, a tribal entity founded to manage, restore and modernize the community’s water system.

The problems on the Gila long predate climate change. For thousands of years, the Pima thrived as farmers on the highly fertile land of the Gila River valley, which they irrigated with complex systems of canals. Through the first half of the 19th century, Pima villages offered hospitality, protection and food to passersby. But the tide of colonialism grew too strong, and in the wake of the Civil War, waves of Arizona settlers encroached upon the tribe’s land and water. By the turn of the 20th century, the Pima had been driven into poverty and famine, and as the years went on, new dams and diversions on the Gila continued to run the river dry.

In 1908, the US Supreme Court ruled in Winters v. United States that tribes had a right to water for their reservations, but it would take nearly a century for the letter of the law to become a reality for the Pima.

It wasn’t until 2004 that the Arizona Water Settlements Act righted this wrong. It legally enshrined GRIC with a water budget of 653,500 acre-feet, or more than 200 billion gallons annually — nearly 10 percent of Arizona’s annual usage at the time. Some 311,800 acre-feet of that budget, which included rights to groundwater as well as water from the Gila and Salt Rivers, would come from the Colorado River via the Central Arizona Project, a 336-mile-long canal. The Gila River community, after years of deprivation, finally had the water it was entitled to. And with new resources came new responsibilities.

The Gila River community is far from the only community in Arizona in need of water. The Phoenix metro area that borders the reservation has doubled in population over the last 30 years, breaking five million in 2022; constituent cities Chandler and Mesa, once rural communities, now boast populations of nearly 800,000. While tighter efficiency rules and the phasing out of water-intensive agriculture for residential development created initial savings, two decades of drought and population growth have put pressure on the cities’ water supplies.

For nearly 20 years, the Gila River community, Chandler and Mesa have been working together on a novel solution. As part of the 2004 settlement, the tribe entered into a water exchange pact with the cities, agreeing to trade part of its Colorado River budget — which the cities needed for potable supply — in exchange for thoroughly treated municipal wastewater for use on the Gila River community’s fields.

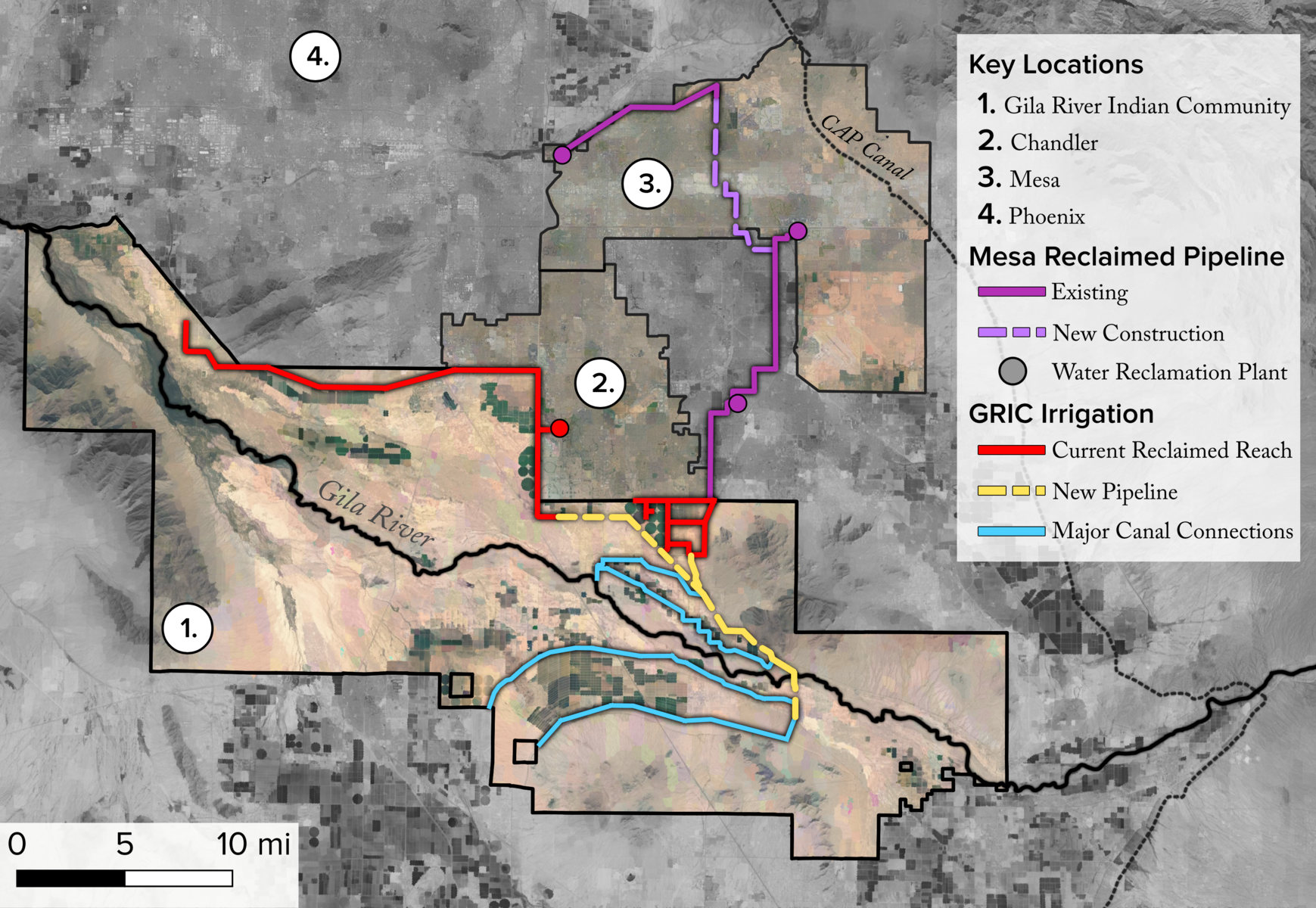

Today, Chandler sends roughly two-thirds of its treated water to GRIC, and Mesa sends about half of its supply. In return, the GRIC sends some 24,800 acre-feet of its Colorado River water to Mesa and Chandler. And because the exchange is set up on a five-four basis, for every four gallons of Colorado water it sends, the community gets five gallons of reclaimed water back.

When the exchange was first conceived, however, not everyone in the Gila River community was happy. In 1967, the Bureau of Indian Affairs — with perfunctory approval from the tribal council — agreed to let the city of Chandler dump hardly-treated sewage on the reservation as part of a city expansion plan. As unsanitary as it was, the wastewater was there, and it would go on to be used for a number of years for reservation agriculture. It was a process borne of necessity, and by the time of the 2004 settlement, few in the community were eager to revive the practice. “People had in mind that that was the kind of water we were going to take,” says DeJong. “But [treatment] technology had changed.”

Not all wastewater is created equal. States generally classify reclaimed water and its permitted uses based on how thoroughly it’s treated. In Arizona, reclaimed water must be of grade “A” or higher to be used in irrigating food crops, but only grade “C” for use on “forage” crops grown for animal feed, like alfalfa, among the primary crops grown on the Gila River reservation. The water that the GRIC now receives is of “A+” quality.

“[In Arizona], we’re at the bottom of the Colorado River,” says Channah Rock, professor and water quality and food safety specialist with Cooperative Extension at the University of Arizona, part of the school’s division of agriculture. By the time that river water reaches Arizona, hundreds of entities — cities, factories and farms — have already discharged into it. “We are essentially using recycled water for agricultural production, we’re just not calling it that.” With proper treatment and careful monitoring, Rock says, reclaimed water can have equal — if not better — quality to traditional supplies.

In addition to the treating and testing that Mesa and Chandler do at their water treatment facilities, GRIC has its own monitoring center and reserves the right to halt the water exchange should its “constituents” — an industry euphemism for fecal and other organic matter — exceed legal limits. “In 20 years, we have never shut the water off,” says DeJong. “In fact, it’s the best quality water we have outside of groundwater.”

Of course, municipal-agricultural water reuse is neither a perfect nor universally applicable solution. For one, agriculture often takes place far from population centers, making transporting municipal water logistically — and economically — challenging. But as water shortages become more severe, the cost of pumping reclaimed water looks smaller and smaller when compared to the cost of a drought-stricken harvest.

Weighed down by negative news?

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.“We are seeing a lot of interest in places we thought water supply challenges weren’t that severe,” says Patricia Sinicropi, executive director of the WateReuse Association, a trade organization that promotes water recycling across residential, industrial and agricultural uses. “The old paradigm of the farmer just putting a pipe in the ground and pumping up the water and not thinking about it, those days are over,” Sinicropi says.

Moreover, while contaminants can be thoroughly removed, stigma is more enduring. That too, advocates say, is starting to change. “Consumers don’t want to know that their strawberries are grown using purified reclaimed water, but because of water scarcity concerns … we are starting to see fights over what is really ‘liquid gold,’” says Rock. “Folks are realizing this is a valuable resource.”

Across the country, that realization has sparked a small but growing practice of agricultural water reuse. Between 2010 and 2015, total reclaimed irrigation grew 42 percent, from 472 million gallons to 669 million gallons per day, according to the US Geological Survey’s most recent water-use census.

The city of Hayden, Idaho uses its reclaimed wastewater to irrigate nearly 500 acres of public-owned farmland on which it grows alfalfa and poplar trees. Monterey County, California, currently treats its wastewater for both groundwater recharge and agricultural use, serving more than 12,000 acres of farmland. East of the Mississippi, the Water Conserv II wastewater treatment plant in Orlando, Florida provides grade A+ recycled water for use on city lawns, golf courses and citrus groves located west of the city, for less than one-fortieth the price of non-recycled irrigation water in the area. “Thousands of people that are moving to Florida yearly, if not daily, and all those households use all that potable water. So the more that we can reclaim helps to preserve that resource,” says plant manager Keith Jordan.

While Orlando’s sprawl has subsumed many of the orange groves Conserv II once serviced, Gila River’s hard geographical demarcation — and a longstanding cultural commitment to the agricultural tradition — protects its fields. Over the last 40 years, two-thirds of the agricultural land south of the Gila River reservation and over half of the land north of it have gone out of production. But for GRIC, having more neighbors in Mesa and Chandler means having a more reliable reclaimed water supply. “The fact of the matter is that people are going to wash clothes, wash dishes, and flush their toilets, day after day after day,” says DeJong. “That’s a constant water supply. Surface water is not that reliable, especially in this time of climate change, especially on the Gila River.”

Now, two simultaneous infrastructure projects — on either side of the city-reservation border — are about to make that supply even more reliable.

In 2022, after years of discussion, Mesa announced the construction of a new reclaimed water pipeline that will finally connect all three of its treatment plants to GRIC. “As we grow, there will be more water usage, which in turn creates more wastewater, which in turn creates more recycled water that we can then deliver to the Gila River Community,” says Chris Hassert, director of water resources for Mesa. The ability to send more water means the ability to receive more water, too.

The Central Mesa Reuse Pipeline, which broke ground in July, is expected to be completed in 2025. It will double the amount of treated wastewater the city sends to GRIC, from 11,000 to 22,000 acre-feet per year. And if Mesa continues to grow as projected, DeJong says, that total is expected to reach nearly 30,000 acre-feet by the end of the decade.

At the same time, the Pima-Maricopa Irrigation Project is hard at work expanding what the community can do with the reclaimed water it receives. In April of this year, GRIC received $83 million in federal funds allotted through the Inflation Reduction Act and Bipartisan Infrastructure Law for a new reclaimed water pipeline.

Currently, only the agricultural land close to the reservation’s northern border — just a fifth of the reservation total — is able to be served by reclaimed water. (The fields in those areas are served by a mix of reclaimed and other water sources.) The reservation’s central valley, home to dozens of growers, including the tribal entity Gila River Farms, is out of reach of the reservation’s most reliable water source. After the new reclaimed water pipeline — which will span 19.4 miles and 100 feet in elevation — is complete, that coverage will reach 95 percent.

“If we had not had a wet year this year, we would have seen a lot of farms fall right out of production,” says DeJong. “This really is a game changer.”

At the same time, the community is working to implement water conservation — and reuse — across all of its activities. This April, in addition to the funding it received for the new pipeline, GRIC also signed a $150 million agreement with the federal government to leave a large portion of its Colorado River water budget in the river, contributing up to two feet in additional storage at Lake Mead. The community is currently constructing a water reuse facility at its new Santan Mountain Casino, which opened in June; by 2025, that water too will flow to GRIC fields. And when there is funding available, DeJong says, the community wants to equip its wastewater lagoons with water treatment facilities tied into the reservation’s irrigation system. “That’s the last of the gold,” says DeJong. “They’re not making any more water.”

Even as the West faces an increasingly precarious hydrological future, Gila River agriculture is uniquely positioned to thrive. With millions of dollars of investment and hundreds of miles of irrigation projects completed and in the works, the Pima are finally — after more than a century of dispossession — reestablishing the resilient agricultural practice essential to their cultural identity. As the Phoenix metro area continues to develop and more of its fields fall out of production, DeJong only sees the role of tribal growers increasing.

“There’s a demand for the food, and somebody’s got to pick that up,” says DeJong. “The community has the know-how, it has farmers who have thousands of years of experience, it has a lot of good land, it has the infrastructure — and it has the water.”