This story was originally co-published by Next City and El Paso Matters as part of their joint Equitable Cities Reporting Fellowship For Borderland Narratives.

In 2010, El Paso native and photographer Peter Svarzbein had a vision for bringing El Paso’s streetcars back to life.

For his graduate thesis at the New York City School of Visual Arts, Svarzbein created The El Paso Transnational Trolley Project — a conceptual advertising campaign imagining the return of the iconic streetcar running between El Paso and its sister city in Mexico, Juarez, as it used to throughout most of the 20th century.

The guerrilla marketing project-cum-installation art included massive posters pasted on walls on both sides of the border, announcing that the trolley, which the city abandoned in 1974, would come back in 2015.

“It was a metaphor to and a symbol of what it meant to be a Fronterizo (a person from the borderland),” says Svarzbein, who served from 2015 to this past January as a city council member and then Mayor Pro Tempore of El Paso. “It’s not the walls or any barriers that define us from being from the border. It is the way that everything passes: Language, food, people, students, music, culture, and religion.”

Unbeknownst to him, about two years earlier and about 2,200 miles away in his hometown, El Paso City Council Member Steve Ortega had also been inspired to bring back the streetcars. By working together and with other local stakeholders, the pair successfully resurrected El Paso’s original streetcars in 2019. While the new route doesn’t cross the border into Mexico, it did serve 47,000 riders during the last fiscal year — at zero fare. In April, seven months into the current fiscal year, 55,000 riders were recorded.

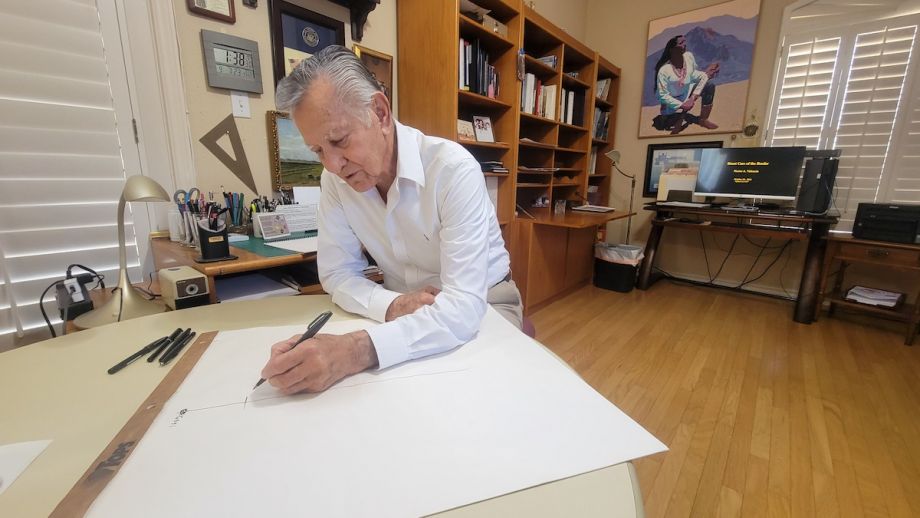

Both Svarzbein and Ortega, who served from 2005 to 2013, credit their interest in the streetcar to their discussions with former city planner Nestor Valencia, who served with the City of El Paso primarily as a planner for about 33 years.

Valencia’s romance with the streetcars began when he was five years old as a rider.

“I love the streetcars because being a kid and getting on the streetcar was a big thing,” Valencia says. “We didn’t have cars, but going to Juarez was big. El Paso is known for two things: the streetcars and the alligators. They’re part of the fiber of the history of El Paso.”

When Ortega began thinking about a way to restore the streetcars, he spoke with Ted Houghton, the Texas Transportation Commission Chair for the Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT).

“He says, Steve, if you can get a plan together, bring it back to me, and we’ll see what we can do,” says Ortega of their first meeting. “So we started a streetcar steering committee.”

The initial committee consisted of eight citizens who contracted the independent firm Cambridge Systematics to analyze the project’s feasibility. Svarzbein later came across this study and realized it could help transform his thesis from an artistic concept to reality.“Cities do a lot of different studies and master plans, and they usually sit on a shelf somewhere,” Svarzbein says. “I didn’t find out till about probably six or eight months into the [art] project that there was a study done.”

After graduating, Svarzbein returned to the city and turned his thesis into an advocacy project to bring the streetcar from concept to reality. Using his guerrilla ad-art campaign to engage citizens, activists gathered more than 1,500 responses through the comment cards the city was using to collect public input for projects to include in the Downtown Revitalization Plan. The comments showed that residents wanted the streetcar to be included among the 2012 Quality of life bond projects, which was overwhelmingly approved by voters.

But the streetcar project was ultimately not included in the bond, since the city council found it could be financed by other means: TxDot funded the $97 million project alone. “TxDOT does mostly road projects on the state highway system, but in this case, we had other monies for transit projects that qualified, and we funded those,” Houghton says.

Construction for the tracks began in 2015. The same year, six of the original streetcars purchased from San Diego in the 1950s — that had been sitting on a desert property owned by the city since the service was discontinued in 1974 —were sent to Brookfield, Pennsylvania. There, they were restored, and modern amenities like air conditioning and Wi-Fi were added.

“A good thing about being in the desert is that there isn’t a lot of humidity,” says Svarzbein. “The cars were in pretty great shape.”

The streetcars officially started cruising the rails on Nov. 9, 2019, with an annual operating budget of $3 million.

Ortega and others interviewed for the story give credit for the streetcars to Houghton, then with TxDOT. He “brought in state money that historically has gone to Dallas, Houston, San Antonio, Austin, and he brought it to El Paso,” Ortega says. “He used his position of influence to better our community. Not everybody does that.”

Not everyone agreed with TxDOT using $97 million to fund the streetcar. Former State Representative and City Councilmember Joe Pickett was one of the early critics of the project due to what he called a lack of a good plan.

“This particular plan was pushed, I believe, motivated by the people who were supporting the ballpark and attractions downtown without a good plan,” he says. “Because of this project, because of this specific project, we changed statewide laws.”

Pickett refers to HB 122, which prohibited TxDOT from issuing new projects financed by the Texas Mobility Fund.

“Myself, the entire House of Representatives, and the Texas Senate have agreed that projects like this were very egregious and self-serving and would not be able to be funded through that process ever again,” he says. “Had there been a better plan where it actually transported people to and from places because all it really is is eye candy.”

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.The money used for the project, Pickett says, would have been better used to fund other projects, such as a truck bypass in the Northeast part of the city — a project that is slated to be awarded in 2025.

Yet Pickett, an avid vehicle collector, admits he has been restoring a vintage streetcar he purchased in 2021 to add to his collection.

For other communities wanting to have similar transport infrastructure, Ortega believes they should learn and understand their city’s history while not being afraid to effect change.

“Things were done 50, 100 years ago for a reason,” he says. “Some of those reasons are still applicable today. The easiest thing for a community to do is to do nothing at all because you upset nobody. That’s not the way you transform and move the community forward. It takes projects. It takes ambition. It takes follow-through for communities to succeed.”

History of the streetcar

The legacy of streetcars in El Paso dates back to 1881, when mules pulled the early vehicles, until they were replaced by electric streetcars in 1902 by the El Paso Electric Railway Company. The cars would freely travel internationally to Ciudad Juarez in Mexico.

Valencia, who has served under 20 different mayors starting in 1964, explains that there had been no bridges that helped people cross back and forth between Juarez and El Paso. Instead, a ferry connected with a rope served as the only means for international travel between the two countries.

“When the floods came, you couldn’t even cross,” he says. “If you wanted to go, you had to swim or walk across. In the winter, you could walk because there was no water in the river.”

The streetcar service erected a bridge that connected the sister cities after the Mexican government gave a 100-year concession to El Paso Street Railway Co. Tolls paid on the Mexican side would go to Mexico. Back then, about 23,000 people would cross the international bridges daily, and about 12,000 people would ride the streetcars.

“They charged a penny and made a lot of money,” Valencia says.

In 1943, the routes were bought by National City Lines and run by its subsidiary, American City Lines. New cars were brought from San Diego and put to operate in the city until 1974 when the program was discontinued entirely.

At its peak, the streetcar service ran 17 lines that covered a 64-mile route, says Everett Esparza, Chief Streetcar Officer with Sun Metro.

In the ‘70s, Valencia was “lured,” as he puts it, to become assistant to the mayor, effectively serving as a city manager for Mayors Fred Hervey and Don Henderson. In his new position, Valencia was tasked to do everything in his power to bring back the streetcars, eventually buying 19 streetcars and the infrastructure for about $90,000 from E.J. Diaz for the city.

“My job was to get them back to Mexico,” he says. “We met with every minister you could think of, governor and mayor. Four years went by.”

Negotiations continued until an agreement was almost made. “We were seconds from get it,” says Valencia. “Then the mayor of El Paso loses the mayoral race, and a new mayor comes in who hated the streetcars. He told me, ‘I want you to never, ever say another word about streetcars again.”

In 1977, the Sun City Area Transit came to be when the city of El Paso bought the three existing bus lines from private companies and made the mass transportation a public entity. In 1987, that became Sun Metro after a one-half penny tax increase was created to fund transit within city limits.

‘A generational project’

The streetcar’s primary draw is its strong history with El Paso. “The streetcar, like San Jacinto Plaza, along with the alligators and the star in the mountain, are part of El Paso’s cultural heritage,” Ortega says.

Beyond downtown revitalization, streetcar’s services are twofold: maintaining a regular route and timely schedule, while including fun programming for riders to enjoy. The streetcar hosts historic tours, readings and NPR Tiny Desk-inspired musical acts that welcome riders at each stop, with events lasting the 45 minutes it takes to complete the route. Sun Metro hopes to soon be able to charter the cars for special events for organizations or family celebrations.

But the transit project is also a major component of the city’s revitalization effort, Ortega notes.

One of the streetcar’s main purposes is to promote transit-oriented development in the city’s two busiest pedestrian areas: the downtown bridge area and the University of Texas at El Paso, which connect through a 4.8-mile circular route.

“The streetcar corridor has transformed in terms of the investment that’s taken place,” Ortega says. “The philosophy is that the private sector knows the streetcar lines are not going to change. They know that the placement of the line is long term, so along that corridor, you have seen significant investment.”

Like other public transport infrastructure in the area, the streetcar’s operations are subsidized to bring tourism and economic development to the city. And at least to some extent, it’s working: The city’s recent impact study into the streetcar found that property values in the streetcar corridor increased by 25.39%, slightly higher than the 24.56% increase citywide. The study also gives credit to the streetcar for creating $121 million in investments, 60 jobs and renovations to three historic buildings, with researchers expecting another $156.7 million in property tax revenue for El Paso over the next 25 years.

Critics of the streetcar point out that the city isn’t drawing any revenue from it. But Svarzbein says they’re missing the point. “It’s part of creating a more active economic and cultural ecosystem for our community,” he says. Cities aren’t making money from people paying $1 or 50 cent fares, he says, but such transit projects are still worth the investment.

“People want to invest in a city that’s alive, that’s full of culture, that’s full of art,” he says. “This is not a project that you’re going to base success off of one year, three years, or even five. This is a generational project. The streetcar symbolizes not just El Paso for the last 100 years, but for 100 years in the future.”

The presence of the streetcars also helps attract tourism to the area for business conferences and railway enthusiasts. “There’s a big contingency of people that are into the rails and these types of streetcars,” says Esparza. “There’s not too many out there. Not all cities have the luxury of having these operating.”

Streetcar operator Valentin Loya, who rode the streetcars as a child and fondly remembers his father talking about the “tranvia,” certainly feels lucky that his city has been able to restore this piece of its history.

“When I had the opportunity to come drive it, I took it because I love history,” he says. “I’ve met people from all over the world, from Australia, New Zealand, Denmark and Austria.”

The pandemic and a migrant influx, among other factors, led to the streetcar temporarily suspending service for two years. And an ongoing lack of ridership — in the first year of service, 220,000 passengers rode the streetcar, which dropped to about 188,000 the next year — put the streetcar on the chopping block once more, as the city considered discontinuing the service in April.

“They’ll tell you that the streetcar is a failure because X amount of people ride it every month, and that costs us X amount of money,” Svarzbein says. “The way that the question is proposed to those metrics is wrong. The question we should be asking ourselves around the streetcar is how much new investment has occurred along the streetcar line in the last five or 10 years.”

Instead, after the new study by city officials, the service was ultimately expanded, with new extended hours for the streetcar beginning last month. The routes’ earlier start and late finish — until 11 p.m. — aim to capture ridership for students and professionals during the day and downtown eventgoers at night.

At any given time, four streetcars will circulate the routes to be at each stop every 10-15 minutes, though traffic jams or obstacles on the road might slow things down. A dedicated app allows riders to find real-time location updates of the streetcars to find them at the nearest stop.

In the future, Ortega says, he would like to see the streetcar expand service into the Texas-Alameda corridor downtown. The area has an abundance of white-collar workers, students, and nurses who would benefit from having reliable transportation to get to work or school.

When the streetcar rolls through downtown El Paso, it reminds Ortega of public officials’ power to create change in their community.

“Some people are happy with just the title,” he says. “But for those who really are interested in community transformation, public services is one way to do that. I feel good when I see the streetcar. It makes me not regret the time that I spent in public office.”