The City of Vancouver’s iconic urban forest known as Stanley Park is widely celebrated for its 500 year old Cedar and Douglas firs, enveloped by the Salish Sea. But few tourists utter the names of the The xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam), Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish) and səl̓ilwətaɁɬ / sel̓íl̓witulh (Tsleil-Waututh) Peoples who still hold rights and title to the land. Instead, they speak the name of a white governor general of Canada from 1888.

Walking through Vancouver parks, you’d have no idea these First Nations were forcibly evicted without compensation to make way for tennis courts and concessions and confined to a fraction of their traditional territories on reserves. As xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam) Chief Wayne Sparrow told CBC News: “There’s more park around our existing reserve than we have reserve land.”

It’s a complicated issue for something like a parks department to wrap its head around. In a move to reconcile these kinds of injustices, leaders declared Vancouver the world’s first “City of Reconciliation” in 2014, which involves a series of commitments to respect and uphold the rights of local Nations and urban Indigenous Peoples. The city commissions Indigenous art and cultural performances. They open events with territorial acknowledgements — statements that honour the specific First Nations on whose land the city operates and benefits from. And the park board recently took steps to explore co-managament of Vancouver parks with local First Nations.

But few of these changes get to the heart of the problem: how do you go about confronting the fact that your institution is responsible for making publically accessible for recreation land that was stolen in the first place? That institutions like parks were not designed by or for the Indigenous people to whom the land they sit on technically belongs?

This is the task of a core group of Indigenous-led staff within Vancouver’s park board who are working to “daylight the colonialism in our system,” as decolonization manager Cha’an Dtut (Rena Soutar), who is Haida, explains, in a first-of-its-kind “colonial audit.” The audit aims to systematically and objectively document how decision-making and funding has and continues to exclude Indigenous people from the city’s parks and recreation services.

“It’s not intended to highlight any one thing and say, ‘This is evil and bad, and needs to go away,’” says Soutar. “It’s just to say, ‘This is how we ended up here.’” A forthcoming report of findings will include data, visualizations and case studies to set the stage for the park board’s decolonization strategy, which will make policy recommendations.

Because municipalities privilege Western forms of data, Soutar calls their approach “colonialism by the numbers.” In a giant spreadsheet they arrange the evidence, from the square footage of land the city has jurisdiction over and plaques featuring colonial names, to exclusionary bylaws and non-native plants. Among the early findings: not a single park is named after an

Indigenous person. As far as park plaques, a handful do mention First Nations — but most are incorrect. “When they said, ‘We’re gonna create parks for citizens,’ they did not mean Indigenous people,” says Spencer Lindsay, who is Métis-Cree and leading the audit. The data reveals “how much time, money and physical space we’ve taken up in parks to tell one side of the story,” Lindsay says.

The terms “truth” and “reconciliation” get tossed around a lot in institutions in Canada, especially since the conclusion of the country’s six-year Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which issued a comprehensive report and detailed list of 94 Calls to Action that Canadian institutions should take to redress the harmful legacy of Canada’s now internationally infamous Indian Residental School system. But how the lofty ambitions of truth and reconciliation actually look put into action on the ground is an ever-evolving process in a country still benefitting from land and resources seized from Indigenous people.

The idea for the audit came from a realization within the parks board that it was necessary to expose the board for its truth before reconciliation. The urge to jump to solutions without this groundwork “invites white saviorism,” she says, and can cause more harm.

“We can’t just forge ahead and rename everything and then expect that that will achieve reconciliation,” says Jessica Carson, a planning analyst who is of settler ancestry working on the audit.

For instance, an Indigenous name would not change the processes that determine who can sell things in parks and who can’t — in other words, who can financially benefit and make their living from that land. Along the beach next to Stanley Park sits a renovated 4,000 square foot restaurant that was once a concession stand. Why did a private company get to redevelop this valuable public space? Who is meant by “public”? Were First Nations with title to the land given the opportunity?

Part of the issue is that most decision-makers in the city are white. “If those are folks who are prioritizing, then a lot of how resources are allocated don’t take into account what might be top of mind for local Nations or the urban Indigenous communities,” says Lindsay.

All staff are asked to contribute to the audit because they are experts in their own work and “the entire structure that determines who gets the land and who gets the wealth, depends on everybody buying into it,” says Soutar. “This is something where I want every person in the organization to feel like they are mentioned, or they have a piece in this. This isn’t a practice for all the managers to decide, and then they’ll go and tell their staff.”

Plus, the colonial audit is “the colonizers’ business,” stresses Soutar. “We’re a colonial government. And this is our work to do, to examine ourselves… there’s plenty of information from Indigenous perspectives already out there without having to draw on additional Indigenous people’s time,” she says.

As far as Soutar is aware, this is the first ever colonial audit, but she actively encourages others to steal this approach, calling it the “Linux of decolonization.” The City of Toronto, following Vancouver’s lead, has included the concept in its first reconciliation action plan that they hope to take to city council in spring 2022.

Vancouver’s colonial audit is not about digging up every racist in the archive — it would be impossible to summarize more than 130 years of history. Instead, they’re focused on how exclusion is ongoing.

View this post on Instagram

While more employees understand colonialism is systemic — meaning collectively, staff members are upholding ingrained racist ideas and policies that cater to white, affulent community members, whether or not they agree as individuals — they might not think day-to-day about how the events that the park board permits can reflect certain cultures and exclude others, explains Carson.

Hesitancy is another barrier. Non-Indigenous people “don’t want to misstep,” she says. “Now that we’re really conscious of racism, we’re trying not to perpetuate it. But I think that we sometimes avoid those harder conversations.” With clear direction and encouragement from management, they’re free to ask and answer hard questions without fear of repercussions.

It’s a sensitive process. “As an Indigenous staff, I’m not here to make sure you never have your feelings hurt,” says Lindsay. “But how do I also inspire staff to know that we all have a stake in this?”

Lindsay’s goal is to relay that decolonization in parks — which urges us to look at other governance models and principles, primarily Indigenous ones — is both ongoing and doable. “Within the next year, not everyone’s gonna come around to a point where they are having an existential moment of saying, ‘Wow, I’ve had a hand in ongoing harm to Indigenous communities,’” Lindsay says.“But I can still get examples of stories where they have felt like the system is blocking them from doing good work.”

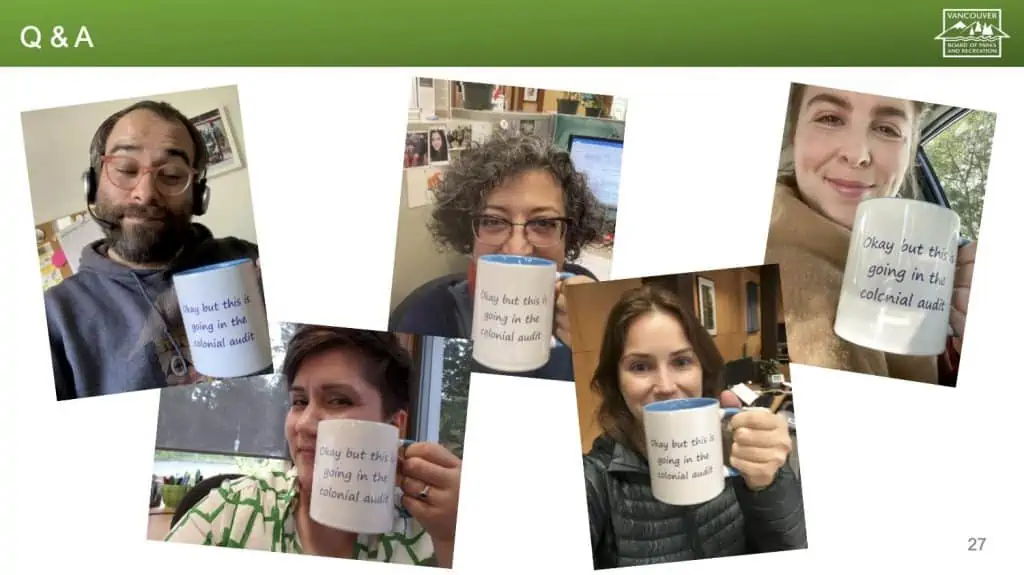

“You can’t always do something about it but you can say it,” says Soutar. As a form of accountability armour, every member of the reconciliation team sports what Lindsay calls a “smug mug.” It arose when a family member of a deceased park commissioner made a request that didn’t align with reconciliation goals. Staff made an alternative suggestion, and wanted to know from Soutar: was that enough? “And so I said, ‘I’m not going to tell you it’s okay,’” recounts Soutar. “‘None of it’s okay…But this is going into the colonial audit.’”