Sleek aluminum housing? Check. A 13.5-inch, high-resolution display? Check. Backlit black keyboard? Check. Fingerprint scanner? Check.

The Framework Laptop might have more than a passing resemblance to the latest MacBook. But it’s different in one key aspect that could kickstart a revolution: repairability.

“Consumer electronics is an industry of disposability,” says Nirav Patel, founder of Framework, the California-based company behind the device. “It was really clear this wasn’t a problem that was going to solve itself. We want to prove that a different model works. You don’t have to get a shiny new product every time something goes wrong. ”

Patel, who previously built cutting-edge hardware for the likes of Apple and the virtual reality headset company Oculus (owned by Meta, formerly known as Facebook), argues the consumer electronics industry is broken. And he hopes the Framework Laptop, dubbed by its creators as “a notebook designed to last,” can help fix it.

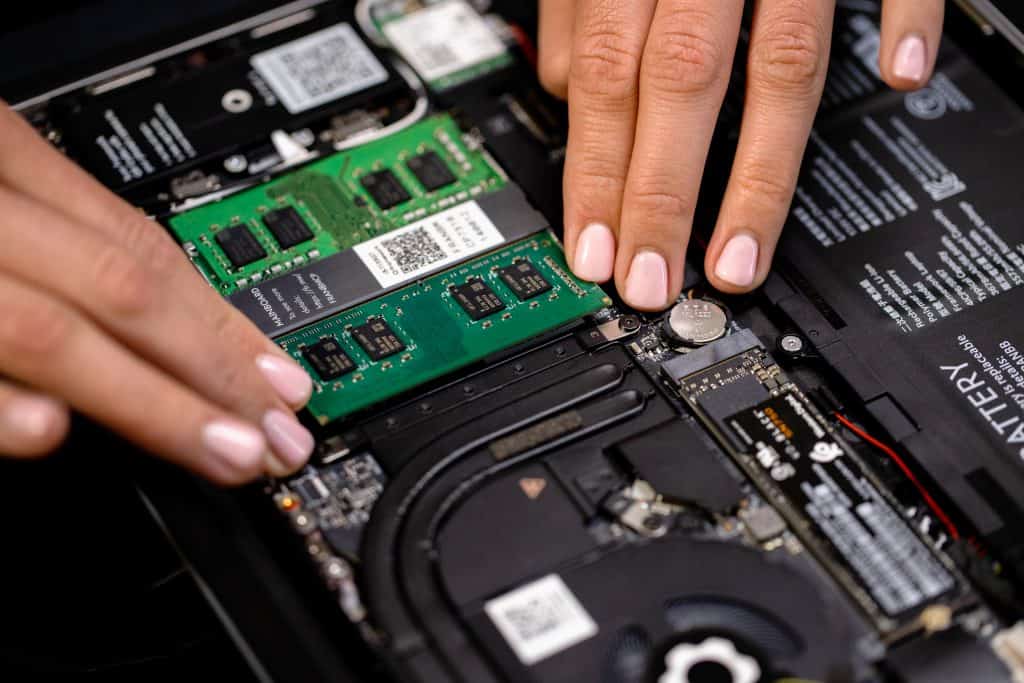

“The entire inside is designed to be repairable,” explains Patel. “We’ve also designed it so that upgrades can be made in the future. Why? It’s about respecting consumer rights and the environment, reducing extraction of the planet’s resources.”

The result is that the Framework Laptop ($999) can be taken apart with ease, and virtually any part of it — from the battery to the processor to the keyboard — can be repaired or upgraded. The constituent parts can be accessed with a screwdriver and a public manual explains how users can make repairs themselves. The ports on the device are simple USB-C boxes that can be removed at the press of a button. The screen’s bezel can be lifted off directly with your hands. And the company just launched Marketplace, which sells affordable replacement parts (a new battery is $59).

With this flexibility, the idea is that users will have greater control over their laptops, which will in turn have a longer shelf life. And Framework insists that despite the focus on repairability and functionality, there will be no genuine downsides. “We could have made it a fraction of a millimeter thinner,” says Patel, alluding to the fact the Framework is 1.58 centimeters thick, compared to the Macbook Pro M1’s 1.56 centimeters. “But the reality is that people don’t have to make trade-offs to get high performance and longevity.”

This simple yet groundbreaking innovation has already earned the Framework Laptop, which began shipping to the U.S. and Canada in July, plenty of plaudits. It is the first laptop ever to receive a 10/10 score by iFixit, an influential pro-repair website. And Framework, which will launch in further countries in the coming months, says it’s been selling more devices than it can produce (though that is partly due to the pandemic’s impact on supply chains).

“We talk about modularity a lot in our teardowns and repair scores,” says Kevin Purdy of iFixit. “Generally, that means that any individual component that fails won’t doom a larger part of the device, or the whole device, to failure. Framework’s Laptop goes above and beyond in that regard. Anyone with typical tools and reasonable skill can access and fix the essential components.”

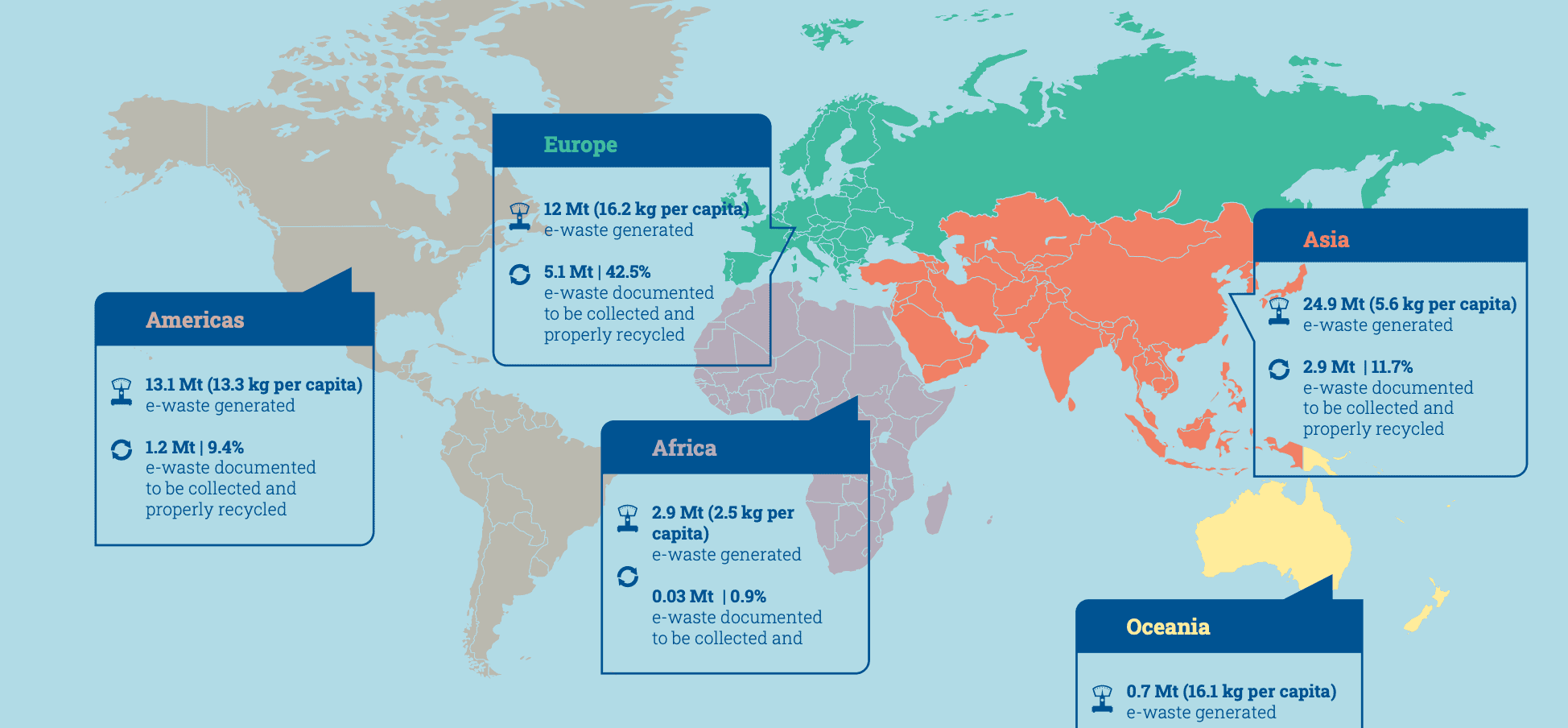

Experts say that reducing unnecessary consumption of electronics is a priority. A record 53.6 million metric tons of electronic waste was generated worldwide in 2019 — up by one-fifth in just five years, according to the UN’s Global E-waste Monitor 2020. That’s set to reach 74 million tons by 2030, making e-waste the world’s fastest-growing source of domestic waste fueled by higher demand for electronics, short life-cycles and few options for repair. The average U.S. household has 25 connected devices, including laptops, smartphones, wireless earbuds, smart home devices and exercise trackers, according to Deloitte’s Connectivity and Mobile Trends Survey 2021.

“The history of the 20th and early 21st century has been a history of consumerism,” says Mark Miodownik, professor of materials and society at University College London. “It’s the economic model to make people buy more stuff. But that’s created an emergency of e-waste and carbon emissions.”

Weighed down by negative news?

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.Planned obsolescence — the built-in deterioration in the performance of devices – has been a key part of many companies’ business plans, according to Miodownik. And so the issue of repairability, he says, is significant not only for the environment, but also for reasons of social justice and global equality. “Making repairs easier redresses that balance,” he adds.

But it’s unlikely to be smooth sailing. There have been notable failures to make modular devices like the Framework Laptop a success. Google’s Project Ara, a modular smartphone with swappable component packs, quietly folded. LG followed suit a few years later with its semi-modular Android device. And although other modular devices like Fairphone are still around, they have yet to break into the mainstream.

“Ten years down the line a lot can change,” says Professor Miodownik. “The Fairphone eventually had design developments that weren’t backwards compatible. And it’s not zero risk for these companies. You have to be confident that people will actually repair these devices, because if you stock up on replacement batteries and they don’t, you’re going to be left high and dry.”

Purdy of iFixit hesitates to predict the success of the Framework Laptop, given variables such as marketing, inventory, production and price picking. But he believes that the initial signs are promising. “There’s a real chance they succeed, and slightly better odds that they influence the market,” he says.

Those odds are likely to be bolstered by the burgeoning right-to-repair movement that is now gaining support from President Biden. In October, Microsoft said it would study the impact of spare parts and repair manuals, and implement findings by 2023. Then the Copyright Office and Librarian of Congress granted blanket exemptions for bypassing copyright schemes if you’re repairing a consumer device (or medical device, or vehicle).

“No one would buy a bicycle if you knew it would stop working in three years,” says Miodownik. “Design for repair is the dominant model for that industry. And it should be the same with technology.”