I used to look forward to the Canada Day parade. I would bring a folding chair and wave a flimsy paper flag on the side of the road in my hometown of Yellowknife, Northwest Territories, watching each float, mounted on the back of a semi-truck, pass me by. At the time, it felt representative of the beautifully diverse, rich and colorful cultures Canada is often celebrated for.

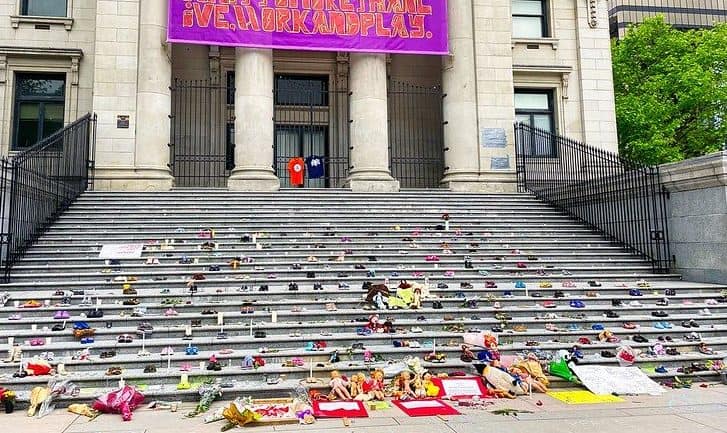

That was before I knew what Canada was really founded on. As I write, the whole world is turning its attention to unprecedented efforts unfolding across the country: efforts to locate unmarked graves of the yet to be known number of children who died in the horrific Indian Residential School System that was the hallmark of Canadian colonialism. At the time of writing, the number of discovered children’s remains found exceeds 1,000, discovered on the grounds of just three of the 130 government-listed institutions that existed in Canada until 1996.

As an Indigenous person and intergenerational survivor of residential schools, I didn’t know the history of what happened to my grandparents and my mother during their time in that system until I was an adult. It was kept hidden because of the pain it caused my family.

This year, I am not alone in questioning the celebration of the national holiday. Now, millions of people across Canada are trading in red and white for the color orange on July 1st. The unprecedented #CancelCanadaDay campaign is a mass recognition of the harms Indigenous children and families suffered during the 165-year residential school reign of terror that underpinned the creation of the country.

Orange Shirt Day — typically observed on September 30 — began in 2013, after Phyllis (Jack) Webstad shared her story of survival as a residential school student at the age of six in the 1970s. When she arrived at the school, she was instantly stripped of her belongings, as most children were, including a brand new orange shirt, gifted to her by her grandmother. The orange T-shirt has come to represent all that Indigenous children endured in the residential school system.

Webstad’s experience, like thousands of others’, was not about learning. The schools — which children were long forced to attend by the Canadian government, often forcibly removed from their families by the national police — were places where children were sexually, emotionally, physically and spiritually abused. Where sickness flourished. Where children were intentionally and systematically separated from their culture and language.

These inflictions often led to children’s deaths. Many also died trying to run away.

Often in Indigenous communities, the mourning of a loved one takes place over an extended period of time where a fire is kept burning day and night. At the rate that children’s graves are being uncovered, that fire will not be put out for at least as long as Canada has been a country.

The Doctrine of Discovery

The soil that buried these children was claimed by the British Colonies under something called the Doctrine of Discovery, a series of decrees dating back to the 1100s establishing spiritual, political and legal justification for colonization and seizure of lands not inhabited by Christians. Non-Christians were said to be non-human, or animal. This notion was used by religious groups to justify land grabs that occurred across all of Africa, Asia, Australia, New Zealand and the Americas — including the United States — despite the millions of Indigenous Peoples occupying those lands. If an explorer claimed to have discovered land in the name of a religion, the land was said to be terra nullius — “the land of no one.” In other words, void of human life.

Heinous as the doctrine was then, it has never been formally repealed. It was the basis of Canada’s Indian Act, which still exists today, and built the foundation of much of the country’s common law.

The name Canada comes from the Haudenosaunee word Kanata, meaning “village” or “community.”

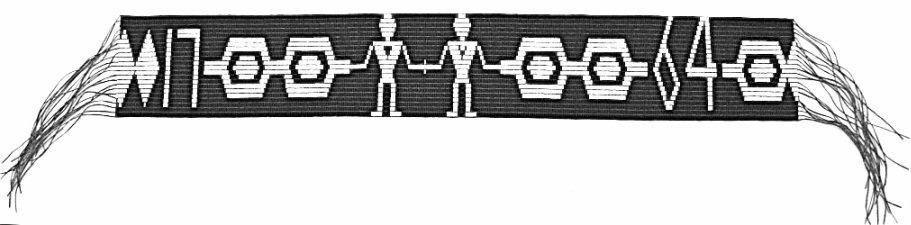

The first treaty ever made in Canada is recognized by many First Nations, but not by the Canadian government. Twenty-four Indigenous Nation leaders showed up at the edge of Niagara Falls in 1764 to discuss peace with the English. Those leaders agreed to let down their guard and accept the promises that were made in the treaty: that trade relations would continue, and that the entire interior of Canada would be known as “Indian Country” as referenced in the Royal Proclamation of 1763.

The Niagara Treaty was recorded in intricate beadwork on nearly 100 exchanged belts called Wampums. Two figures on the Wampum belts holding hands symbolized friendship and alliance. But when the full impact of the Royal Proclamation came into effect, King George III claimed ultimate dominion over the entire region of Canada, turning his back on the promises of the Treaty. To this day, that claim remains arguable in the courts that are trying to determine Indigenous and Crown titles.

“A place where we acknowledge the same stories”

Change is happening in Canada, in large part due to the work of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) — an official body established by the largest class-action settlement in Canadian history. The TRC travelled the country for six years, between 2007 and 2015, hearing testimonies from over 6,500 witnesses of the residential school system and its intergenerational impacts. At its conclusion, the TRC issued a final report including 94 Calls to Action to Canadian institutions to action reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples. Slowly, they are being put into effect.

This National Indigenous Peoples Day for example, Canada made changes to its Oath of Citizenship. The Oath now refers to the rights of Indigenous Peoples, fulfilling Canada’s commitment to the TRC’s Call to Action number 94. The Oath recognizes Indigenous rights found in section 35 of the Canadian Constitution Act, 1982, which acknowledges that Indigenous Peoples occupied North America since time immemorial — a stark contrast to the Doctrine of Discovery. As new Canadians recite the Oath, they are asked to make a personal commitment to observe the rights of First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples. It is meant to educate newcomers about their role in reconciliation.

Indigenous people can also now reclaim their traditional names on passports and other documents, fulfilling TRC Call to Action number 17.

Most importantly right now, Calls to Action numbers 71 to 76 call on the federal government to provide substantial support and resources for efforts to find the remains of children who died in residential schools, and to support families and communities in reburial and commemoration efforts.

But while the federal government may be making incremental efforts at reconciling past wrongs, it is the municipalities across Canada that are really stepping up. The City of Victoria, British Columbia’s capital, was the first city to cancel Canada Day celebrations this year in order to provide an opportunity for thoughtful reflection on what it means to be Canadian.

This shows what can happen when reconciliation is taken seriously. The city has been doing the work since 2017, when it embarked upon its commitment to reconciliation with the surrounding First Nations by establishing a City Family, composed of a combination of City Council and staff members, and appointees from the Esquimalt and Songhees Nations.

Janice Simcoe, an Ojibway woman and member of Chipewyan Rama First Nation and visitor on Lekwungen territory for the past 40 years, is one of the City Family Members, upon request of Songhees Nation and with the support of the Esquimalt Nation. The reasons for moving from her birthplace, she says, were strongly related to the existence of residential schools: hers was one of the many families who fled.

Weighed down by negative news?

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.Simcoe says the first discovery of a mass gravesite of 215 children in Kamloops, British Columbia this May was the proof for the rest of Canada to really understand. “It was evidence of known stories. It was evidence of known histories. We knew that it was going to result in Canadians finally learning the truth part of truth and reconciliation.”

At a commemorative event on the legislature lawn on June 7, a week after the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation publicly announced the discovery, Victoria Mayor Lisa Helps asked for recommendations from the City Family on what to do on Canada Day. Each member agreed that hosting a Canada Day celebration would be extraordinarily painful and that it would be unimaginable to participate.

“It doesn’t mean it’s over. It means that we’re honoring something different this year. Honoring it through reflecting, through silence,” says Simcoe, who believes that Canada Day will change from here on. “It has to. We have to have the acknowledgement of truth when we are celebrating.” She hopes that in the future “we can come to a place where we acknowledge the same stories.”

So far, communities and municipalities across BC, Saskatchewan, Yukon, Northwest Territories (NWT), Nunavut and Ontario have made announcements that they are not going ahead with planned celebrations, and that momentum is growing.

In my hometown of Yellowknife, the Rotary Club that puts on the parade each year stated in a press release on June 26 that holding a parade would go against its guiding principles as an organization; that they were canceling the Canada Day parade out of respect for the Indigenous communities who make up a full half of the NWT population.

Needless to say, it’s not the job of Indigenous Peoples to educate others. Allies are helping to do that heavy work. Alexia Manchon, a supporter of the Wet’suwet’en pipeline protests, says “as settlers, we need to understand that all the ways we benefit from living here are built on the destruction of Indigenous governance, culture and people. We need to do so much better at listening to what Indigenous communities are asking for.” Manchon says that starts with respecting the countrywide mourning in the wake of the discoveries and continues with holding accountable the institutions that represent Canadians.

Kanata

When I was a child, I remember having to stand and sing along to a choppy recording of “Oh Canada” on the loudspeaker at school. Today, my middle school-aged daughter doesn’t have to do that. It leaves me wondering if the celebration of Canada Day will also slowly sizzle out like a cheap firework.

Will so-called “Canadians” look back in a few years’ time and ask why they participated in a holiday that was more about a long weekend of beer and backyard barbecues than reconciling the dark history of the country they were celebrating?

I know I won’t. This July 1st, I will be wearing orange in memory of the hundreds of children whose lives have been lost. I will show up in orange with the hope that this country will one day stand up to its rightful name, Kanata.