This story was produced by CBC q, a We Are Not Divided collaborator

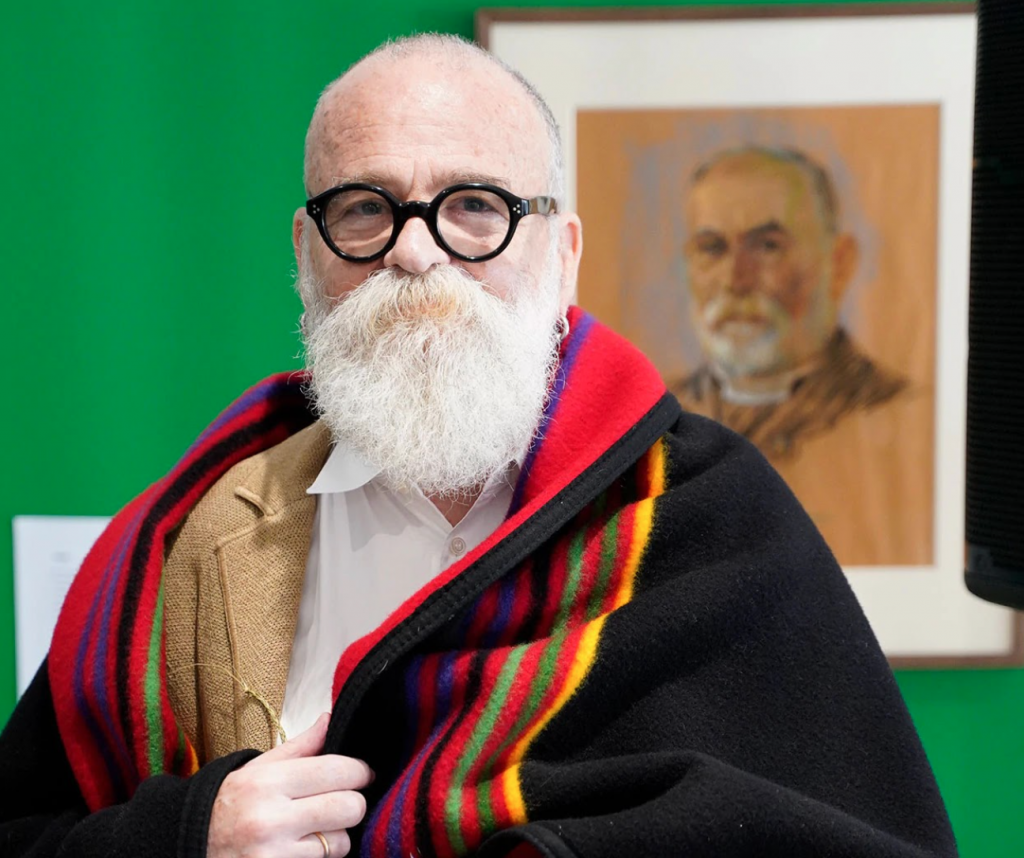

Standing in front of an audience at last fall’s Toronto Biennial of Art, AA Bronson was nervous. As a member of the General Idea collective, founder of the NY Art Book Fair and a leading conceptual artist, the 74-year-old was no stranger to public performance — but this was different.

For the first time, Bronson was going to deliver his text A Public Apology to Siksika Nation — the culmination of a five-year project he had been “hurtling towards” for the last seven decades. It was so essential that when he started it, he stopped making other art.

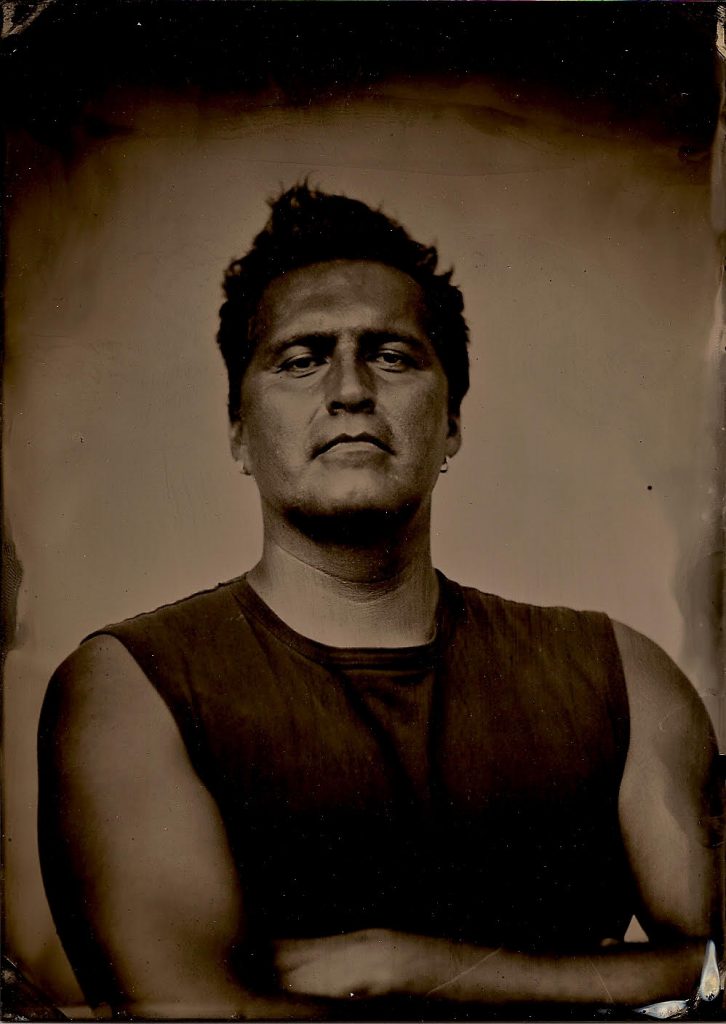

Two-spirit Blackfoot artist Adrian Stimson, clothed in ceremonial dress, was among those who had gathered, along with several Siksika elders, all of them survivors of Canada’s notoriously brutal residential schools — including the Old Sun Indian Residential School, which operated on the Siksika reserve until 1971.

Bronson — who was born Michael Tims — and Stimson have a lot in common. They’re both queer artists working in a range of media; they’re both known for groundbreaking performance art; they’re both recipients of Governor General’s Awards and other high honors.

But their history dates back to over a century ago to the Alberta plains where their ancestors were sworn enemies.

Stimson’s great-great-great-grandfather was Chief Old Sun, a renowned Blackfoot leader and reluctant signatory to Treaty 7, the 1877 agreement with the Canadian Crown that imposed the reserve system and removed most of the Siksika’s rights to their traditional lands.

“He was highly suspicious of the newcomers,” Stimson says in an interview with q host Tom Power. “He didn’t want to sign the treaty, but in the end he acquiesced. He was a bit of a rebel and a very fearless leader.”

Six years later, in 1883, Bronson’s great-grandfather, Rev. John William Tims, became the first Anglican missionary sent to the Siksika nation, where he was tasked with building the community’s first church and residential school.

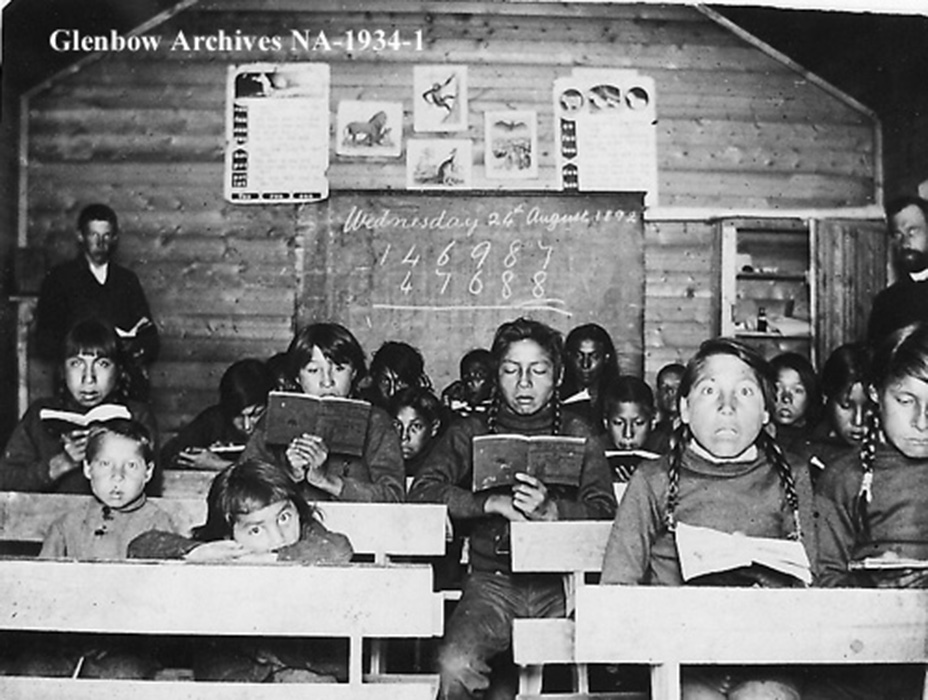

As was the case across Canada, Indigenous children were taken from their parents and forced into residential schools where they were physically, sexually and emotionally abused, creating profound intergenerational trauma that still ricochets through the community half a century after Old Sun closed. Many call it a cultural genocide.

“[Rev. Tims] took the children away from their parents, he forbade them to speak their own language or practice their own customs or wear their own clothes,” Bronson says of his ancestor. “And he did his best to destroy Siksika culture.”

In a bitter twist, the Siksika school was named after Stimson’s ancestor, Chief Old Sun.

“It’s ironic that his name would be used in an institution that was meant to kill the Indian in the child,” says Stimson, who himself suffered abuse at residential schools.

According to oral histories from both artists’ families, diphtheria and tuberculosis swept through the schools in 1895.

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.

“Children were dying, and sadly, Reverend Tims would not allow those children to go home,” says Stimson. “So you can imagine the sadness and anger the parents felt.”

An uprising followed, and the church and the school were burned to the ground. Siksika people warned Tims he should leave or he would be killed.

For decades, Bronson wanted to confront this history in his art. The combination of his advancing age, growing public awareness of Indigenous issues and a call from the Canada Council for works that marked 150 years of Canadian history spurred him to move ahead.

While various governments and religious groups have offered apologies, Indigenous people continue to be overrepresented in the country’s jails and prisons, face racism in policing, and have higher rates of violence against women, poverty and infant mortality.

So when Bronson first approached the community about making an apology, they hesitated.

“There’s the saying, ‘Walk the talk.’ And when apologies are given, often the walk afterwards is either nonexistent or very slow. So there is cynicism,” says Stimson, who took the idea to Siksika elders. Myrna Youngman, one of the elders, noted apologies were rare, and suggested they listen.

“The cynicism went away at that point, and we decided that this is important,” remembered Stimson. “Let’s listen to him. He’s approaching us in the right way.”

He invited Bronson, who stepped into his artistic alter ego Buffalo Boy — a wryly humorous and gender-fluid spin on Buffalo Bill — to the Siksika Nation for a special dinner.

At the table, Stimson and several elders asked difficult questions about the nature of apologies, and the painful history between Rev. John William Tims and the Siksika people.

“It’s really meaningful that you’re acknowledging what your grandfather did. He wasn’t made to do it. He did what he did and you’re acknowledging it, which means a lot,” says Youngman, pushing back tears, in an episode of CBC’s In The Making that documented the dinner.

Stimson also took Bronson to the school.

“I don’t know how it stays standing,” Bronson says. “If I were Siksika, I would burn it down again.”

Bronson, along with research assistant Ben Miller, spent months poring through archival photographs, journals, documents and news reports. Many accounts had portions destroyed or removed, in particular, those that dealt with the uprising.

“In the records of the Anglican Church, there was no such uprising — just Tims was reassigned to a different church after some vague trouble. It really was erased from history,” says Bronson. Through Miller’s diligent research, they pieced the story together.

“And of course, the story comes from the dinner table. It comes from stories that my father told and my grandfather told.”

In Bronson’s apology, which he published as a book, he speaks directly to Old Sun, Red Crow, Chief White Pup and other chiefs of the late 19th century; to the children who suffered at residential schools; to the parents who lost their children to abuse and disease; to the medicine men who couldn’t attend to the dying; and to those who participated in the Siksika uprising.

“I have no excuse for the slaughter of the buffalo, nor the genocide of First Nations,” he writes. “I have no excuse for decades of mass incarceration and abuse of children, disguised as residential schools, disguised as ‘for their own good.’”

Bronson also speaks to those in later generations who have experienced abuse, HIV/AIDS, suicide and murder. At the end of the book is a meticulously detailed timeline of events, an essay about the Siksika rebellion and archival photographs.

“It’s an invocation of the dead. It’s inviting the dead to join us in considering this piece of history. And I do believe we are a community of the living and the dead. We can’t escape that. The dead are part of us, and that needs to be acknowledged,” says Bronson.

“And that harm that my ancestors did to Adrian’s ancestors needs to be acknowledged and brought into the room. And we need to sit with that history.”

Stimson has heard and read the apology many times. But he is clearly moved when he hears Bronson read from it.

“It still resonates,” he says, his voice cracking.

“When the government apologizes, that’s fine, and a lot of people did a lot of work around that. But the real acts of conciliation happen between individuals.” (Stimson prefers to say conciliation, arguing that conciliation needs to be achieved before reconciliation is possible.)

“It’s the people themselves who have to take it upon themselves to find ways of creating relationships,” he says. “And it may not always end up in an apology. But it’s so important to understand that history, and look to ways of repairing or creating new relationships into the future.”

As an artistic response to the apology, Stimson created Iini Sookumapii: Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner, a recreation of the dinner table where he and the elders first met with Bronson, which was also on show at the Toronto Biennial.

Stimson asked Old Sun survivor Gordon Little Light to build a table similar to one that might have been found at the school, then appointed it with fine silver and dinnerware — a stark opposite to what Indigenous children would have experienced.

“Then I put a little bronze bison on each plate, sort of looking at the diner as a way of interrogating,” explains Stimson. For millennia, bison were a primary source of food, clothing, commerce and ceremony for the Blackfoot people; white settlers wiped out their population, leading to deprivation and starvation.

“A lot of my work deals with the slaughter, which is very analogous to what happened at the table.”

A vase of white roses with one red rose, symbolizing the government’s aggressive push for assimilation, also sat on the table, while a light from the Old Sun school hung above.

Behind the table, a large photograph featured a group of boys at the school, some of them looking despondent, others smiling.

“It really struck me that all of those boys are now our fathers here on the nation, many who have passed and some who are still with us,” Stimson says.

“Although many were smiling, you could only imagine the heartache that existed from being taken away from their families and having to live in that school — and I certainly know that from my father’s own stories of being in that place.”

While the collaboration was first brought into public view at last year’s biennial, it didn’t end there. After witnessing the apology, Stimson and the elders shared it with the Siksika community. The book has also been widely distributed within the nation.

This spring, Stimson had planned to host a powwow where Bronson would make the apology directly to the community. But the Covid-19 pandemic put those plans on hold.

Of course, no apology could ever properly address a genocide, Bronson says.

“There’s no way to make up for what was done,” he says. “That’s impossible.”

Still, their collaboration speaks to the power of individual action. Recently, Stimson had to prepare a statement about the abuse he suffered at residential schools — a task that invariably triggers profound sadness and anger. But in the process, he realized working with Bronson has been healing.

“I know for the elders who were present, they’ve felt very much the same. They really felt somebody listened to them. And in listening to them, that hurt and that anger, that resentment, all those things that come with that history are somewhat lessened,” says Stimson.

“It never will ever go away. But at the same time, as you build trust, as you build friendships, as you come to know and come to understand that in the hearts of many people, there is a willingness to change and to address these things and move forward in a good way,” he says.

“Seeing that certainly gives us hope that other people will start doing this, and actually really start walking the walk of an apology.”

Digital lead producers: Tahiat Mahboob, Ruby Buiza | Copy editor: Lakshine Sathiyanathan | Web development: Geoff Isaac | Video producer: Andrew Alba | Radio producer: Cora Nijhawan | Executive producers: Ann MacKeigan, Paul Gorbould