“She had very long locs that would go all the way down to her waist,” Avery Smith describes, his fingers making imaginary strokes from his head across the shoulders as he attempts to paint a vivid portrait of LaToya, his late wife.

The Baltimore-based software engineer and LaToya, a podiatrist, tied the knot in 2008. One day, around a year and a half into their marriage, “when she was doing her hair, she found a nodule — basically, a raised mole — that was at the base of one of her locs.”

She got it biopsied the same day. Two weeks later, when results returned, she was diagnosed with Stage 2A Melanoma, a milder variation of the deadliest skin cancer. According to the Melanoma Research Alliance, a minor surgical procedure is usually enough to cure it. But the following 18 months were revealing for Smith; on December 9th, 2011, LaToya died. In addition to the heavy loss, he was left scarred by the experience: “I learned about going through illness while being Black,” he says.

Today, over a decade later, Smith is putting his skills as a software developer to work in an effort to end the racial bias and inequity in skin care that contributed to his wife’s death. In 2021, he launched Melalogic, a Baltimore-based startup that provides skin health resources to people with dark skin, and is working with crowdsourced imaging data to tackle racial bias in diagnostic artificial intelligence (AI).

The bias Smith is tackling is staggering. The American Cancer Society reports that melanoma is over 20 times more common in white Americans than it is in Black Americans. According to the study, 1 in 38 white people stand a lifetime risk of getting melanoma. In comparison, that number is just 1 in 1,000 for Black people, because melanated skins produce melanocytes — color pigments resistant to sun damages, including those responsible for skin cancer. While this would ideally translate to a lower mortality rate, the opposite is true. A 2016 study shows that the five-year survival rate of Black people with skin cancer is 65 percent, compared to 92 percent for white people.

The problem is rooted in racial inequities and biases in medical research and technology. In skin cancers, for instance, AI systems have been used to drastically improve diagnosis, inform decisions and facilitate treatment leading to positive health outcomes. However, these are mostly helpful to white people because diagnostic AI datasets are trained with images of white skin.

The same issue persists in other areas of medicine. Medical illustrations for example, which medical professionals learn from and consult, are overwhelmingly portrayed with white skin. Dermatologists, of which only three percent are Black, often lack the capability or understanding to treat darker skin shades, and are likely to resort to medical myths. For instance, a 2016 study on pain perception found that half of the white medical trainees believe Black patients have thicker skin and are more resolute to pain than other races.

That’s why in 2018, Smith teamed up with dermatologist Dr. Adewole Adamson to conduct a research project, endorsed by the American Medical Association, on machine learning and health care disparities in dermatology. The findings proved what he already knew: that doctors see the issue of racial bias in medicine, specifically towards skin cancer, but that little had been done to act against it to prevent negative outcomes.

“Blind spots in ML (Machine Learning) that reflect the worst societal biases have been described before when the technology is applied to images: misreading Asian faces as blinking, mistaking images of black people for gorillas, or judging only white faces as attractive,” the report read. “Because ML is only as good as the data from which it learns, great care must be placed in building technology that reflects the diversity of skin types in our society.”

It was from the research’s findings that Smith conceived Melalogic, an app that he hopes will eventually become the single go-to resource for Black skin health.

In its current form, Melalogic — funded in part by a grant program from Mozilla that supports Black artists addressing biases in AI, with the hope of securing venture capital in the future — is dedicated to providing Black people with skin health resources, with expert contributions from Dr. Chesahna Kindred, a black dermatologist and Hillary Wilson, a certified medical illustrator.

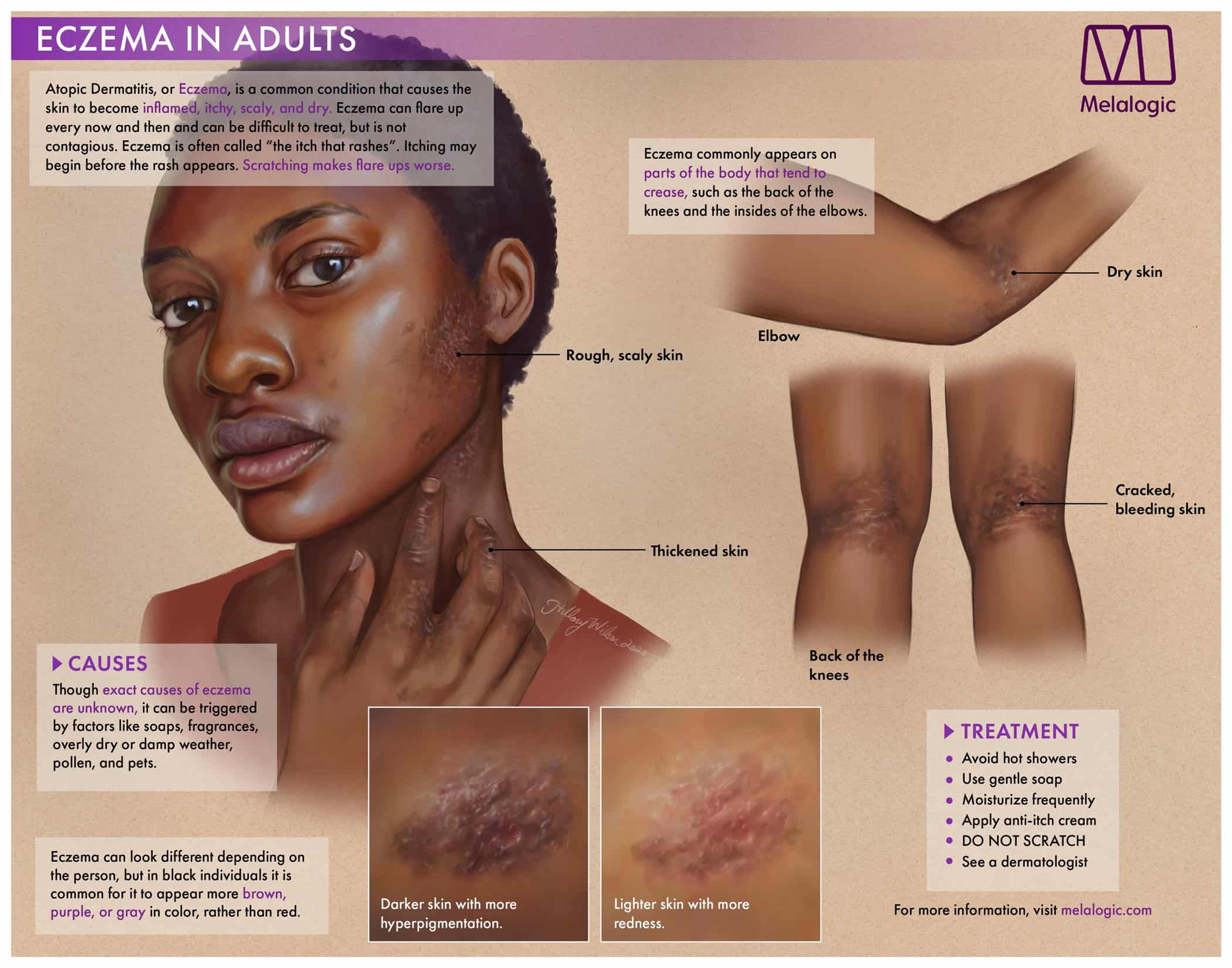

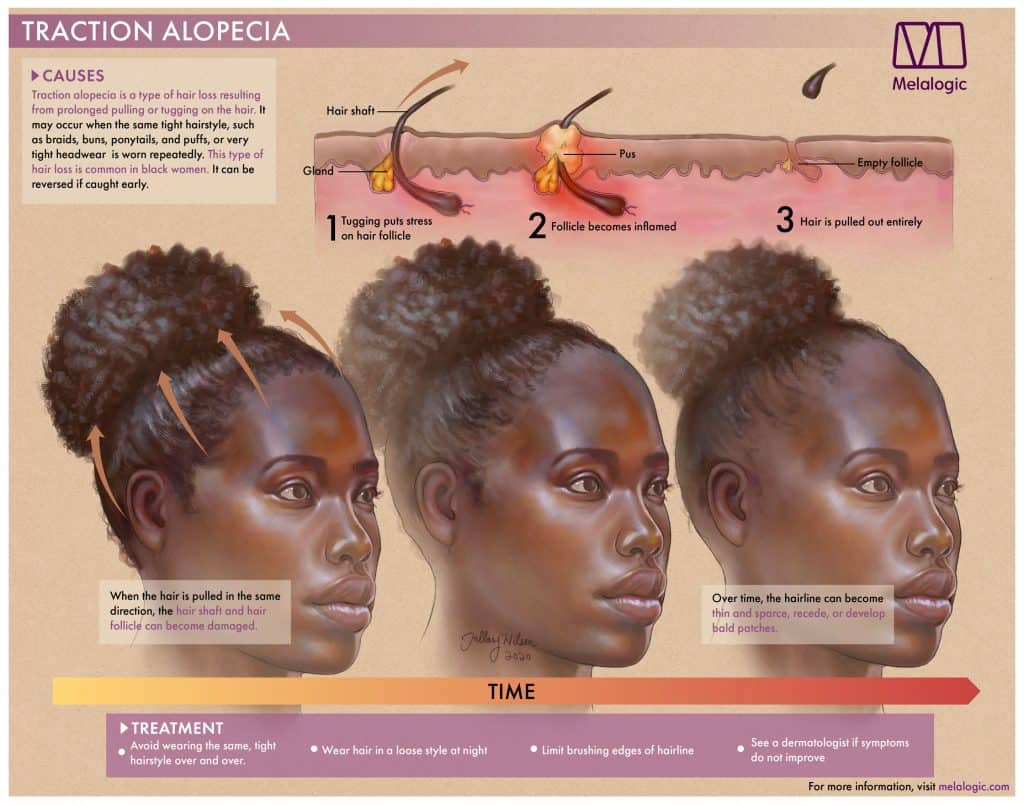

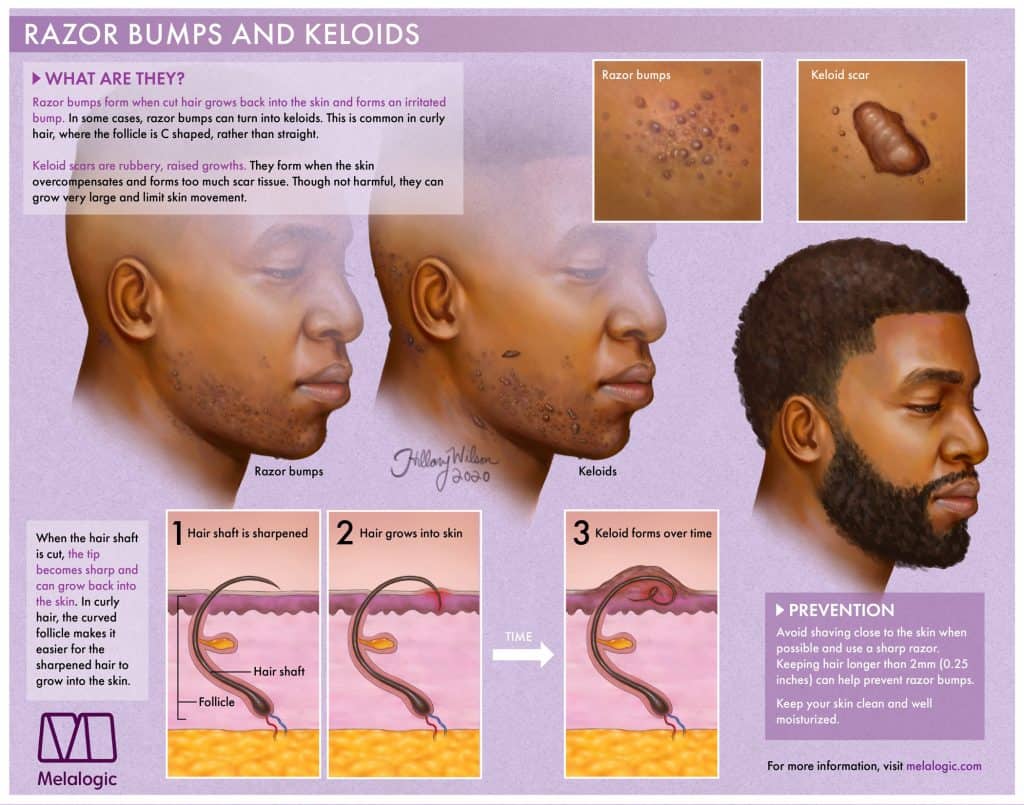

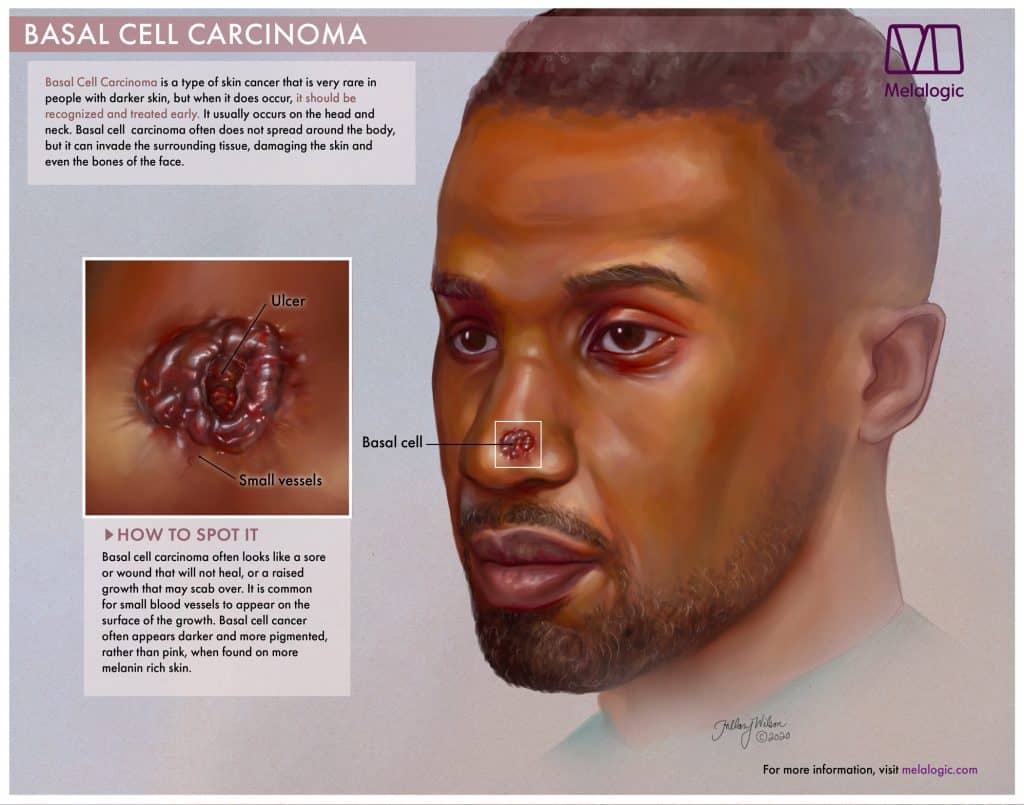

When logged on to the melanated-themed web app, users gain access to the Black Skin Resource Center, a repository with 14 different issues that affect skins in melanated tones, searchable by keywords. From mild issues like acne, eczema and razor bumps to more complex ones like keloids, alopecia and varying forms of melanoma, each has a digestible but medically accurate explainer accompanied with Wilson’s infographics, with overview provided by Kindred.

“Dermatology is a visual science, so we need to be able to just look at it and figure out the diagnosis or the most likely diagnosis. But when we don’t know what we are looking at, we are likely to miss a pretty deadly condition if it’s left unchecked, and that’s a huge problem considering the demographics of our country,” says Kindred, who also serves as the chair of National Medical Association Dermatology Section.

Wilson details the many ways this plays out. “For example, hyperpigmentation is very common in melanated skin, and someone may erroneously believe that hyperpigmentation is the result of poor hygiene.” In contrast, erythema, a type of skin rash that can range from mild to indicative of a deadly infection, can be less obvious in melanin-rich skin. “Some conditions that may appear pink or red on lighter skin may appear more brown or purple on darker skin,” she says. The app is meant to curb these misconceptions that can lead to serious medical missteps.

Aside from dermatologists and regular users, other health care providers benefit from more robust resources too. Memphis-based dietician and trichologist, Samaria Grandberry uses nutrition and products to treat hair and scalp issues to a clientele base with darker shades of skin. One challenge she faces is that medical illustrations are not representative of the skin she treats. Or, in cases where the ailments are exclusively related to darker shades of skin, there is a complete lack of visual aids.

“I was really excited to come across Melalogic,” she says. “While searching on Google for medical posters, you see a lot of the same posters over and over but that was the only one that popped up and showed brown skin and even some of the physical features of brown skin and brown hair.”

The posters have helped improve understanding and trust with her patients. Now, alongside other nutritional posters, she has them hung in her office.

“It’s been really helpful for my client to truly see what’s really happening,” she says. Her clients often take photographs of the illustrations and request personal copies on occasions.

At the bottom of each webpage, Kindred shares dermatologic tips via video, such as how to recognise diseases like Acral Lentiginous Melanoma, the most common type of melanoma in people with darker skin; infamously the cause of reggae legend Bob Marley’s death. Melalogic also offers a Black Skin Health eCalendar, which sends users healthy skin tips and advice every month and can be synced with Apple or Google Calendar apps, and a directory to access 90 Black dermatologists across the United States, searchable by location.

The app’s biggest-picture offering, though, is the option of contributing to the startup’s ultimate goal: its Black Skin Health AI Dataset, which has to be trained by crowdsourcing thousands of pictures of melanated skins. Users log on to the web app to snap and upload a photo of their skin condition, labeling the image with what they think the issue is. In the backend, dermatologists access the imagery employing the Five Safes model for user privacy, further diagnose the ailment and sort them accordingly into the dataset.

Smith’s goal, Melalogic 2.0 which is set to launch within about a year, is an immersive telehealth experience. “Ultimately, you can get instantaneous feedback as to a particular skin condition when you take a photo,” he says. The Black dermatologists directory will be built out to include professionals outside of the United States as well as the ability to purchase products and services tailored to Black skins. It is, Smith says, about time.

“Even in 2019, and before, a lot of people were very timid when using the term ‘Black’… That’s not helping things,” he says.

“People are starting to see that, wow, Black people really do have their own needs that need to get met… It’s just in a lot of areas, we are different. And that would require an entire class of products and services that is specifically designed for people with this particular quality and characteristics.”