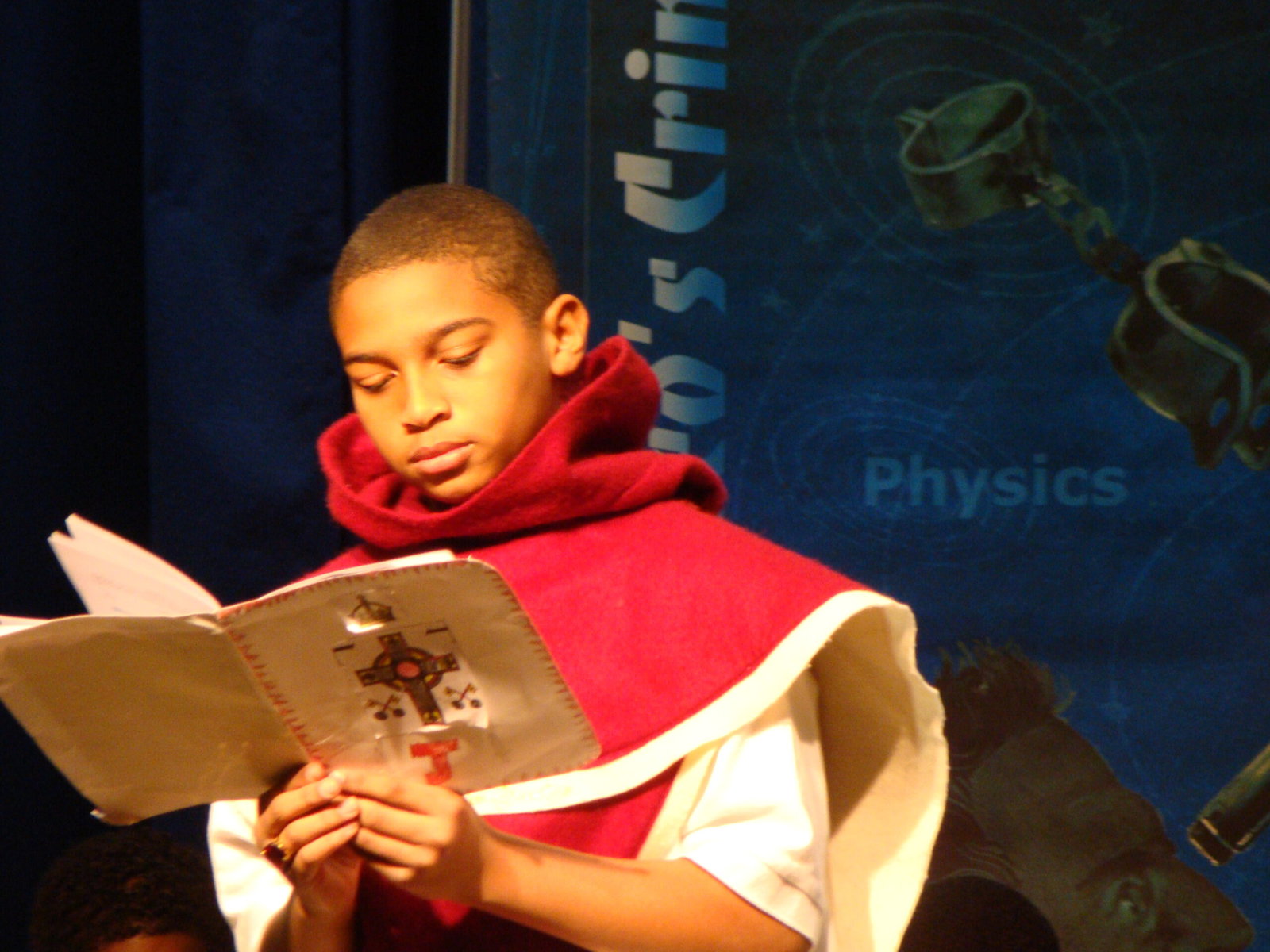

Eleven-year-old Carlos is buckling under pressure. The sixth-grader at Lilla G. Frederick Middle School in Dorchester, Massachusetts, is the lead in his school play, acting as the young Siddharta Gautama, who is struggling with leaving his palace before he becomes known as Buddha Shakyamuni. But the young actor is fighting stage fright.

“Carlos, who do you want to be?” the Spirit Series leader challenges him.

“Give him a break!” another student shouts.

“No, I will not give him a break,” the trainer responds. “Carlos is a great prince, and like Prince Siddharta now, he must make a great choice.”

The last run-through this morning was bumpy, and the class hadn’t even gotten through the script in full, but now the entire class is supporting their classmate, shouting “Carlos, Carlos,” urging him to go back on stage.

Crucially, the casting for this play was by lottery. Carlos did not ask for the main role, but now he has to step up.

Screenwriter Richard Strauss designed it that way. When Strauss’s first wife passed away in 2000, it was a shock for him and their then-10-year-old daughter, Molly. “I saw that my daughter was facing the kind of challenge and adversity she really wasn’t prepared for,” he says.

Strauss, who has written for Fox, MGM, Paramount, Columbia and Showtime, naturally turned to what he knows best: storytelling. “I had the idea that perhaps stories of great heroes and the way they met challenges and hardships in their lives could be inspirational to her,” he says. “But I had never written for children before. So it took me about a year before I realized that I didn’t have to write for children. I believe the program is so successful because the plays are very, very challenging for fourth- through 10th-grade students.”

He wrote scripts about the lives of the Buddha and Socrates for sixth-graders’ ancient history curriculum, about Sitting Bull and Harriet Tubman for fifth- and eighth-graders’ American history curriculum, and about La Malinche, a key figure in the conquest of the Aztecs, and Galileo for seventh-grade world civilization classes. He calls this collection of plays the Spirit Series, “because it’s a celebration of the human spirit and because our job is to spirit students over a threshold in a transformative way.”

The principal at his daughter’s elementary school had lost her own mother when she was nine and developed a close bond with Molly. Her school hosted the first plays, and the principal advised him to design the plays to fit in with the standard school curriculum, so that teachers could fulfill their education goals along with Strauss’s objectives.

With encouragement from Howard Gardner, the renowned developmental psychologist at Harvard, who encouraged creativity and learning in the arts, the Spirit Series has since been hosted by more than 100 schools and 60,000 students in California, Maine and Massachusetts.

Weighed down by negative news?

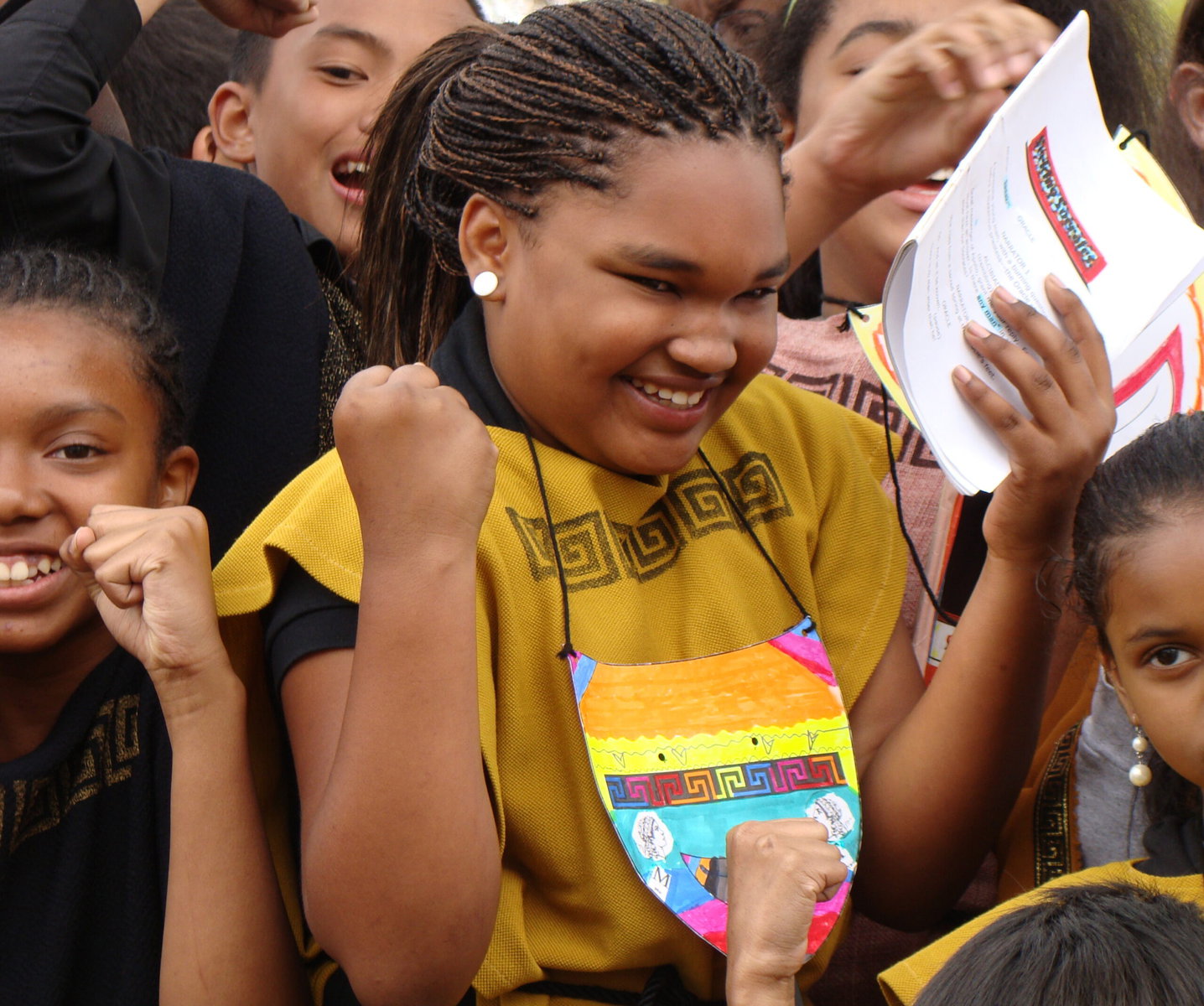

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.The results students and teachers report are striking: More than a quarter (25.3 percent) of students improve academically and in social and emotional skills. More than 90 percent of students report improved teamwork after participating, schools count a 32.3 percent decrease in absenteeism during the Spirit Series residency, and nearly 82 percent of participating teachers said that the series elevates focus. “Spirit Series works in so many diverse school communities because it offers the kind of engagement and meaning that students desperately seek, but cannot find elsewhere in their education,” Dr. Paul Cummins, the founder of Crossroads School in Los Angeles, says.

“We were amazed how far the series took our students in just three weeks,” says Cheryl Merz, a middle school principal in Lawrence, Massachusetts. “The residency was intense and demanded a great deal. This showed our teachers just how much our children are able to achieve when they are pushed to do so.”

The Spirit Series team provides masks, costumes, tableaus and a trainer who takes the class from introduction to the final performance in three weeks of daily one-hour sessions. “I really liked how it’s a very different kind of learning,” says Alec, a sixth-grader who played a role in the Socrates play at the Revere Middle School in Los Angeles. “Instead of taking notes, you could step into the character’s sandals and experience the feelings that they feel.”

Unlike in regular theater plays, the Spirit Series plays leave room for the children to insert their own dialogue, put themselves in the historic figures’ shoes and write essays about big questions posed by the historic figures in the plays, for instance: What do you want out of life when you grow up? Does popularity feed the soul? And is it more important to live or to live well?

“It’s the age when the horizon of their lives gets much larger, these questions are bubbling up inside of them, and nobody is giving voice to them,” Richard Strauss says. “Of course, when my daughter was struggling with grief, she wasn’t the only one dealing with adversity and hardship in their lives and asking the biggest questions.”

Crucially, once a school decides to host a play, participation is not optional. Every student has a speaking part, and the leads are cast by lottery. “So the lead might be somebody who has language challenges, and then they have that opportunity to step up and reinvent themselves,” says Leslie Rachel Strauss, an artist and co-director of the series. “We have had blind students play the leading role or kids on the spectrum or a student who reads three grade levels below the class, and then they’re tackling the Socrates play, show up in the library and practice their lines every day at lunch.” She calls these performances “definitely the most rewarding. I think this speaks to needs that are unexpressed and unrecognized.”

Richard and Leslie, who are married, have identified nine needs they are addressing with the plays, whether the students are contemplating Lakota virtues or the eightfold Buddhist path: meaning, challenge, belonging, adventure, stillness, self-expression, wonder, service and safe passage to adulthood.

“When you learn to play the singing bowl, you understand that stillness is an imperative,” Leslie Strauss gives as an example. “The kids don’t know they’re looking for stillness until they encounter it.”

When the Spirit Series started 24 years ago as a nonprofit, neither Richard nor Leslie Strauss imagined that they would eventually give up their jobs and spend their days working with school kids, but they both describe the joy of seeing the students transform as the biggest reward.

“At the end of each play, there are a few kids who don’t want to leave,” Richard Strauss has observed. When he first started introducing the plays, “Dominka, a seventh-grade girl who had been the quietest girl in the class, came up to me and said, ‘You know, this changed my life.’” Richard Strauss says. “That did it for me.”

Richard and Leslie Strauss both have dozens of anecdotes of students who were withdrawn or selectively mute and came out of their shells. Leslie Strauss remembers a class where all students were on the autism spectrum as “among the most extraordinary performances I’ve ever seen, and every one of their students was transformed by the experience as well as their parents.” She says many parents were moved to tears during the final performance.

“Since the dawn of time,” Richard Strauss notes, “society has understood that culture is providing safe passage to adulthood” for children. This, he says, can be done in two ways: “One is the profound power of story. That’s how you convey the value, you never preach anything. You just tell the great story and embedded in that story are all the values that a student or a young person needs to navigate life. And the other thing is you put them through a very significant challenge.”

Since the pandemic, the Spirit Series has expanded into Spirit Corps, which provides video-assisted storytelling that the Strausses are rolling out more widely this year, and Spirit Works, a coaching program for teachers, “because you can’t expect students to go where you can’t lead others,” Leslie Strauss says. “Transformative outcomes in classrooms begin with self-transformation.”

In Dorchester, Carlos takes a deep breath and steps onto the stage.

The Buddha is awakening once again.