After the 2008 financial mess, austerity was touted as an economic cure-all. Deep budget cuts were forced upon nations and their citizens as a prerequisite for bailout loans. Now, we’re seeing the fallout. Anti-austerity protests have gripped countries around the world, from Chile to Ecuador to Lebanon to Zimbabwe. We should have seen this coming—austerity isn’t the only option, or even the best one, for countries in fiscal distress. In fact, one country has proven that rejecting austerity is not only a way to survive, but to flourish. That country is Portugal.

Compare Portugal today with Britain. One could argue that the Cameron administration’s austerity policies created the anger and frustration than eventually led to Brexit. Austerity in Italy and Greece, too, seems to have fostered a surge in far-right politics. What’s worse, austerity hasn’t even done what it was supposed to: save faltering economies. A paper issued by the IMF’s chief economist five years after the financial crisis concluded that every dollar cut from government budgets actually reduced economic output by $1.50.

Portugal took a different tack, rejecting the austerity approach, and the country is now paying off its debt, restoring confidence and seeing an upswing in economic growth and prosperity.

In other words, the story we were told by many economists and governments—that extreme belt tightening is the only way out—was wrong. There was and is another way.

A tiny bit of background

After the banking and credit mess of 2008, austerity—government measures taken to reduce spending, usually in response to a debt crisis and often combined with privatization—was frequently touted by politicians and economists as the ONLY way out of the debt hole dug by the bankers. In nation after nation, public services like health care, arts and culture, education and social security were cut, wages and pensions were frozen, and funding for many programs deemed inessential was reduced. Public assets were often sold to private corporations to quickly raise money.

As a result, health, infrastructure and education (among much else) suffered. Life expectancy actually dropped in the U.K., and the British Journal of Medicine estimated 100 additional deaths per day could be attributed to the policy. As a result, there were massive anti-austerity demonstrations in Spain, Greece, the U.K., Ireland, Canada, Germany and Nigeria. Folks felt left behind. Not just felt—they WERE left behind.

What happened in Portugal?

As with many countries, after 2008 Portugal found itself deep in debt. So, in 2011 it took out a $92 billion loan from the IMF. In return, the government agreed to drastic spending cuts: pensions were reduced, wages frozen, public utility companies privatized and the national airline sold off. Sales taxes on cars and tobacco rose, and unemployment benefits were cut from three years to 18 months.

Quickly, pain and resentment grew. Youth unemployment neared 40 percent, and former professionals were reduced to selling goods out of their homes to keep food on the table. During the first year of austerity, the Portuguese economy contracted by 3.2 percent. “It is indeed to be feared that austerity is paving the way for an authoritarian turn,” concluded a 2012 analysis.

It felt to many people as if the bankers got a bailout and citizens paid the price. From the Guardian:

In a two-year period, education spending suffered a devastating 23 percent cut… Unemployment peaked at 17.5 percent in 2013; in 2012, there was a 41 percent jump in company bankruptcies; and poverty increased. All this was necessary to cure the overspending disease, went the logic.

Austerity had similar effects elsewhere. A few years after severe cutbacks were instituted in Spain, unemployment jumped to 27 percent, the highest since recordkeeping began. In Britain, a U.N. official compared austerity’s effects to a Victorian workhouse, saying that its “punitive, mean-spirited and often callous” implementation had spawned “a great misery.” All of this is not actually news. In Germany in 1932, the Social Democrats gave in to austerity programs, which drove unemployment up to over 40 percent. We all know what came next.

This is not the place to go into the pressures that were used to justify austerity policies. Rather, in the spirit of Reasons to be Cheerful, I’d prefer to look at a successful alternative.

Rejecting austerity

In 2015, fed up with four years of cutbacks, leftist Portuguese political groups united to mount a campaign that promised to curtail austerity measures. They won the election, and began making good on this promise on multiple fronts.

First, they offered incentives to foreigners—both individuals and businesses—to come to Portugal. Lured by tax incentives, Google and Mercedes-Benz expanded their presence and hired thousands of local employees. So did technology giant Bosch, which grew its workforce at a single campus in the city of Braga to 3,000 workers. The government also began offering five-year resident visas to foreigners who invested at least 250,000 euros in Portugal, a scheme that has brought over $5 billion into the country.

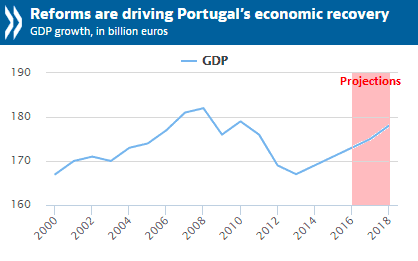

In addition, the government raised minimum wage and pension payouts, giving people more disposable income to pump back into the economy. It also returned public sector wages to their pre-crisis levels, some of which had fallen by 30 percent. Nearly five years later, Portugal’s economy is humming along, growing at 3.5 percent in 2017 and 2.4 percent in 2018, its fastest expansions in years.

From the New York Times:

The government’s U-turn, and willingness to spend, had a powerful effect. Creditors railed against the move, but the gloom that had gripped the nation through years of belt-tightening began to lift. Business confidence rebounded. Production and exports began to take off.

At a time of mounting uncertainty in Europe, Portugal has defied critics who have insisted on austerity as the answer to the Continent’s economic and financial crisis. While countries from Greece to Ireland—and for a stretch, Portugal itself—toed the line, Lisbon resisted, helping to stoke a revival that drove economic growth [in 2017] to its highest level in a decade.

The new government’s policies also led to a more ephemeral change: a shift in attitude. Today, the Portuguese are feeling better about their country. A 2011 Eurobarometer survey found that 44 percent of respondents felt that the country would be worse off one year in the future. By 2018, that number had fallen by half.

This isn’t just feel-good stuff—when people and businesses are confident in a country’s future, they invest accordingly. For instance, the Times spoke with an olive oil producer who decided to purchase new harvesting technology after austerity measures were rolled back. “The actual stimulus spending was very small,” one economics professor told the paper. “But the country’s mindset became completely different, and from an economic perspective, that’s more impactful than the actual change in policy.”

It also encourages those who have left to return home. As NPR reports, Portuguese youth who left are coming back to the country and investing in new businesses:

“My friends, people I know, who were leaving the country more or less at the same time I did, in 2011 and 2012, a lot of them came back already or want to come back,” Mouraz says. “They come full of motivation, with knowledge from other countries and a different mindset.”

They are also finding jobs. Wages are up, and Portugal’s unemployment rate has dropped to around 10 percent from a high of nearly 18 percent in 2013.

Portugal’s economic stability has held fast. In 2017, the country exited the EU’s excessive deficit procedure, and recently posted its biggest budget surplus since adopting the euro 20 years ago. No surprise, then, that the European Commission recently concluded that Portugal’s serious macroeconomic imbalances had been resolved.

Other factors at play

By rejecting austerity, Portugal has gone against conventional economics, and in the process, earned its share of critics, some of whom have raised legitimate questions about the government’s methods. For instance, the increased spending on pensions and wages was offset by cuts to public works, like railroads and hospitals, which by some measures have deteriorated since being defunded.

Luring foreigners has also made the country more expensive for locals. The aforementioned five-year visa scheme seems to be contributing to affordability problems in Lisbon. So is a boom in tourism, which, while good for the economy in general, has led some landlords to rent to foreigners instead of locals, at inflated prices. Between 2013 and 2017, the number of visitors to Portugal rose from 8.3 million to 12.7 million, and Lisbon surpassed Barcelona and Paris as the European city with the most Airbnb rentals per capita.

I was in Lisbon during my world tour last year, and things did appear to be booming. That feeling is purely subjective, but we got a view of Rust Belt towns in the U.S., U.K., Poland and Slovakia, so there is a comparison. Construction, busy shops and restaurants, folks out and about, socializing — we could see for ourselves that folks are moving to Portugal…word is out that it’s a good place to live. My bandmates told me that an increasing number of important musicians are leaving Brazil, which is going through a rough economic and political patch, and moving to Portugal. So the mood in Portugal is generally upbeat, as anti-austerity policies have led to prosperity. But it’s important to acknowledge the growing pains that have accompanied the recovery.

A model for others

Following the Reasons to be Cheerful rulebook, I wondered if the types of policies Portugal has implemented have worked elsewhere. As it turns out, they have.

President Obama’s stimulus package, as modest as it was, kept the U.S. economy from collapsing during the banking crisis. And just as in Portugal, a chorus of conservatives warned against it: “Stimulus couldn’t work because of some weird debt trigger condition, or because it would cause hyperinflation, or because unemployment was ‘structural,’ or because of a ‘skills gap,’ or because of adverse demographic trends,” writes Ryan Cooper in The Week. “Yet it’s been six to eight years since their arguments and there’s hardly been a glimmer of the kind of inflation they warned about… In fact, not only has there been no hyperinflation, inflation has consistently come in under the Fed’s supposed target value of two percent.”

Quite a few Latin American countries have taken a stand against austerity, too. In recession-plagued Argentina, the previous government was ousted last month when voters roundly rejected its cutbacks. Chile has been rocked for weeks by protests that began with a subway fare hike and have since morphed into a broader fight against cuts to health care, education and other public services. There have been demonstrations against cuts to fuel subsidies in Ecuador and health care in Honduras.

In many cases, the austerity measures being rejected began with IMF loans.

Michael Cohen (NOT Trump’s former fixer!) writes for the Journal of Social Research:

This decision [to roll back austerity measures] has largely been successful. Latin American experience of more than 60 years strongly suggests that policies restricting spending [on public services] can have major negative impacts on national economic growth and social welfare. Those promoting spending, on the other hand, have a greater likelihood of maintaining aggregate demand at the macroeconomic level while providing key services and infrastructure needed for minimal levels of well-being.

They’re not out of the woods yet…

In Portugal there is still a LOT of debt to be paid off—the country’s debt is about 120 percent of its GDP, the highest in the eurozone after Italy and Greece. Plus, as Brazilian professor Nuno Teles points out, tourism is a dicey foundation on which to build a recovery. And some of Portugal’s success is due to pure luck.

But overall, the case of Portugal is hugely encouraging. It’s proof that austerity bromides and policies are not necessarily the only solutions to economic problems. Given these examples, economists and financial advisors around the world might begin to revise their recommendations—resulting in less pain, less suffering and healthier economies worldwide.