The caller says he just got a text message from a woman he recently started dating, accusing him of sexual assault. “Describe to me what happened,” JAC Patrissi calmly requests on the other end of the line. As the caller takes her through the events of the evening, Patrissi chimes in at crucial intervals and homes in on the occasions when the caller’s partner sent signals of discomfort and refusal that the caller chose to ignore.

“You know how it gets,” he says.

“Well, no, tell me how it gets,” she counters calmly but firmly, before the caller falls silent and comes to the conclusion, “Yes, this was sexual assault. I didn’t have consent.” The man wants to know if he might face charges. “You might,” Patrissi answers honestly before asking the vital question: “How are you going to let this change you?”

Patrissi, a trauma clinician, co-founded the helpline A Call for Change to fill what she saw as an urgent need: A way for people who cause harm to seek expert help confidentially and anonymously. While there are batterer intervention programs in nearly every US state, they are often court-mandated and take place in the framework of law enforcement. This helpline is different: The calls are not recorded, and they are entirely voluntary and anonymous. What’s more, after much debate among staff and after hearing the experience of helpline operators in other countries, Patrissi’s team decided to uncouple the initiative from police enforcement.

“This is crucial,” she says. “People, especially from marginalized groups, wouldn’t call us if we were working with the police.” Even if an abuser confesses to a crime, Patrissi’s staff of 10 won’t notify the authorities. The only exception would be a crime in progress (and only if the responders knew the name and location of the caller), but this hasn’t happened since they started operating in April 2021.

About 41 percent of women and 26 percent of men in the US have experienced violence or harassment by an intimate partner, according to the CDC. Fifty-five percent of female homicides are committed by current or former intimate partners. The pandemic, with its extended lockdowns, exacerbated the problem. “In the US, we have carceral police-based containment and control, called batterer’s intervention or intimate partner abuse education,” Patrissi says. “During the pandemic, it became clear that intervention focusing primarily on survivors leaves a lot of problems unaddressed.” Not only were abuse incidents becoming more frequent during the pandemic but shelters were closed or limiting their capacity.

“Especially in rural Massachusetts where we are, you can’t just get in a car and drive away,” Patrissi says. “Your community is here, and your livestock. Access to vehicles is limited. This approach never really worked for rural folks.” Also, she asks, why is it always the survivors who must uproot themselves and leave their homes when it’s the abusers who committed the violence? “Why is the person who’s being harmed the one expected to disrupt their life, their children’s schooling?”

Before Patrissi launched the helpline, she says, skeptics predicted hardly anybody would call. But it’s quite the opposite. “People who cause harm are just so relieved they can finally talk about it,” she says. “It’s usually us who have to end the call after an hour and a half when people can’t stop sharing. These people are intensely isolated.”

The helpline received more than 200 calls in the first year, and 400 in the first nine months of 2022. About 70 percent of callers seek help for themselves, and 30 percent are family members or experts who are calling in to ask how they can help an abusive partner, friend or client. A disproportionately large number of calls come from marginalized communities, including LGBQT youths, and Patrissi believes this is “because they don’t trust law enforcement and don’t know where they can find help.”

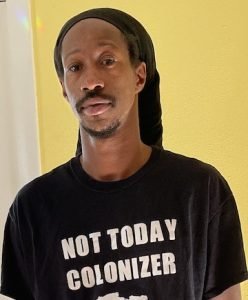

Conventional abuser programs have dismal completion rates with dropout rates of up to 89 percent. “Recidivism rates are high,” says Regi Wingo, A Call for Change facilitator who has 14 years of experience in the field and helped train the helpline’s responders. “The survivors are not the problem. Sure, they need support, but we need to address the root of the problem. We’re always pulling drowning people out of the river, so let’s go upstream and address the problem at its source.”

One criticism of the punitive approach is that it is authoritative and can reinforce feelings of shame and alienation. “You sit around with a bunch of dudes most of which don’t want to be there and have no interest in changing,” Wingo has observed in court-mandated groups. “This is very different from having a one-on-one conversation with someone who really wants to change. You can give them a choice: What do you want the next 20 minutes of your life to look like? Do you want to be taken away in the back of a police car or do you want to sit on the porch, chill out and learn how to become a safe partner?”

A Call for Change, which gets funding from the state’s Department of Public Health, was initially intended for rural Massachusetts, but accepts calls from people all over the US. Eleven other states, including California, Wisconsin, Vermont and Colorado, are looking into setting up their own helplines.

Accountability with compassion

Australia, the UK, Sweden, Colombia, parts of Canada and other countries have offered helplines for abusers for decades. One of the earliest, the Respect Phoneline, has been answering calls in the UK since 2004, and receives more than 6,000 calls from abusers seeking help every year. There is no universal playbook for preventing intimate partner abuse, and each helpline follows slightly different principles. But overall, studies show that intervention can significantly decrease violence. For instance, a six-year study of 11 intervention programs in the UK found that violent incidents decreased from 61 percent to two percent among participants.

“I know from running groups, there is a big difference, an enormously positive shift when you are not mandated to go, when you choose to pick up the phone yourself because it’s confidential and you can tell the whole truth about everything you’ve done and there’s not a system of control attached,” Patrissi says. After three decades in the field, she rewrote the toolkit for conversations with abusers.

One of the principles she and the responders abide by is, “Compassion without accountability is collusion. And accountability without compassion is domination.”

“If you’re just focusing on, ‘You’re wrong. Look what you’ve done here!’ that’s not the doorway,” Patrissi says. “The doorway to accountability is human compassion. But we hold people accountable through the dialogue and it’s very uncomfortable.”

Patrissi, the only white person on her facilitation team, also stresses the importance of having a diverse group of responders. She founded Growing a New Heart to offer community training for people interested in learning how to facilitate transformative justice in their communities. They don’t have to be trained psychologists to qualify.

Of course, deep-rooted problems are rarely solved with one phone call. “Most of the callers have multiple issues, so our responders give out a lot of referrals: How is your housing? How are your resources?” Patrissi says. The responders will often direct callers to local resources, whether for therapy or practical help. “You don’t cause harm because you are unhoused, but being unhoused or substance abuse might add to your agitation, and if you are a person who believes it is okay to be abusive when you are uncomfortable, then we want to find resources to minimize that part of the stress,” Patrissi explains of the policy. More than two-thirds of callers keep calling back. “That’s part of the impact. We can be their community until they find other people who are actually willing to help them see how their actions impact other people.”

The helpline will direct survivors in acute mental crisis to mental health specialists, and child abusers to Stop It Now, a national nonprofit that is solely focusing on preventing child sexual abuse. There are already resources in place for them, Patrissi says.

Critics have said she’s offering mere “confessionals” where abusers can relate their crimes and feel good about having downloaded their take. Patrissi shakes her head. “This is where accountability comes in. We have callers who say, ‘My therapist told me what I did is not a big deal. Nobody ever held me accountable.’” Because all responders are “very seasoned,” according to Patrissi, she is convinced they can see through the “fake crying that often happens right after the harm where it’s still all about them. We’re waiting for that moment of silence at the other end of the line where the truth will sink in.”

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.

Patrissi knows the issues from personal experience, having grown up in a violent home, and later finding herself in an abusive relationship. She has worked in survivor services for decades, eventually training as a trauma clinician. She has primarily supported survivors but also gained experience within certified batterer’s intervention programs, thus gaining insights into psychology and effective treatment for both victims and abusers. For her, it was hard to develop compassion for abusers. “The other day, I had a call from someone who had lost all his friends because of his behavior. I said, ‘That must be hard for you,’ and it took a lot for me to say this.”

She refers to this process as a “lifelong piece of work.” Patrissi shares insights into her approach that differ from conventional wisdom, including the trope that abusers need better communication skills. “There are highly educated lawyers who are abusive at home,” she says and reveals that the abusive relationship she found herself in was with a professional therapist who was on the board of a domestic violence intervention program. “He had all the skills in the world,” she says, “but he wasn’t applying them when he assaulted me.”

She believes that help for abusers is “not necessarily about their skills, it’s about their belief they are superior.” Sometimes, she says, abusers will employ these techniques during phone calls. “They will try to enact dominance, make our responders feel inferior,” she recounts. “Our job is to hold up the mirror and make them recognize their patterns.”