There’s a disability that affects three-quarters of Americans. It’s one that, globally, contributes to an annual loss of over 60 million collective years of life. That disability is vision loss. And while vision loss is debilitating for 4.6 percent of Americans, the vast majority of those with imperfect vision are largely unencumbered by it thanks to corrective lenses.

This experience of having a disability accommodated is so common that most people hardly think of vision loss as a disability at all. But for people with more serious disabilities, it isn’t so easy. One in four Americans has a serious cognitive or physical disability that affects their daily lives: 13.7 percent report mobility issues, 10.8 percent report cognitive impairment, 6.8 percent report difficulty living alone and 3.7 percent report difficulty in self-care, dressing, or bathing.

For these people, an affordable place to live that accommodates their disability is essential — and often, difficult to come by. “Living options for these people with disabilities are limited to being institutionalized or semi-independent living with [their] biological family, who are often overworked and too burnt out to provide such care,” says Esther Lee, an attorney at the Disability Law Collective. Lee has cerebral palsy, a disability that, as she puts it, affects her speech and mobility, but not her spirit.

Lee is a co-founder of Able Community, a non-profit co-housing cooperative designed for folks with disabilities. Able Community operates a house in a suburb of Chicago that balances interdependence with independence — an opportunity that, for folks with disabilities, is rare.

https://www.instagram.com/p/BbLKSMaBimr/

Alongside advisory board members, the house’s residents, including Lee herself, control and coordinate resources and care services, like food purchases, health care and maintenance. Through fundraising and pooling resources, they have been able to maintain the property and renovate the house to be more accommodating to their particular needs.

Beyond physical accommodation, the co-op has also brought members a sense of community, belonging and joy. “Community means having friends you can count on, who encourage one another, and problem-solve issues faced together,” says Lee. This is what differentiates the Able Community from typical housing for folks with disabilities, which is typically controlled by government agencies, companies, or families.

Money is a major barrier to independent housing for folks with disabilities. The structure of benefit programs like SSI, SNAP and Medicaid create paradoxes for recipients. SSI recipients, for instance, can earn only up to $65 per month before SSI benefits begin to phase out. “People with disabilities often need to choose between benefits (e.g., health insurance that covers meds, equipment, care services, etc.) and earning more than poverty level wages, which would disqualify them from any benefits and make them pay for everything themselves at exorbitant costs,” says Lee.

In 2019, only 19.3 percent of people with a serious disability were employed. And while Americans with serious disabilities qualify for Social Security Income, it is hardly enough to cover living expenses. In 2020, the maximum SSI monthly payout for an individual is $783, not enough to cover the median rent in any U.S. state. Over the last decade, the SSI benefit has grown by roughly 10 percent. Over the same period of time, nationwide rent increased by 46.5 percent.

Weighed down by negative news?

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.This is where Able Community’s model bridges the gap between affordability and autonomy. Supported by private donations, grants and member income, the housing is cheaper than market-rate renting and more independent than institutional housing. Services and essential purchases are collectively arranged, though Able Community makes clear on its website: “No, we are not a commune.” The organization has plans to build a 20-unit inclusive co-housing community “committed to including people with disabilities, open to a wide range of incomes, skills, and capacities.” The main barrier is not the imagination, will, or ability of the Able Community — just resources.

Proof exists that it can be done, however. The Able Community’s goal of providing affordable, accessible co-housing at scale might look something like The Kelsey, a mixed-ability housing non-profit based in San Francisco.

Funded through grants, city funding, individual donations, investors and sponsors — including Google and the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative — The Kelsey works to advocate for and directly build disability-inclusive housing in California. Building any new housing in California — especially in the Bay area — is an uphill battle, but in under two years, The Kelsey has secured permission for 240 new units of housing. The first project, set to break ground this winter after being delayed by the pandemic, is the Kelsey Ayer Station in San Jose.

The 115-unit Kelsey Ayer Station will be joined by the Kelsey Civic Center, a 125-unit development in the heart of San Francisco. Both will rent units at a number of income levels, and a quarter of the Civic units will be rented through the San Andreas Regional Center system, a branch of California’s network of private-public partnership organizations that coordinate and provide services to Californians with disabilities.

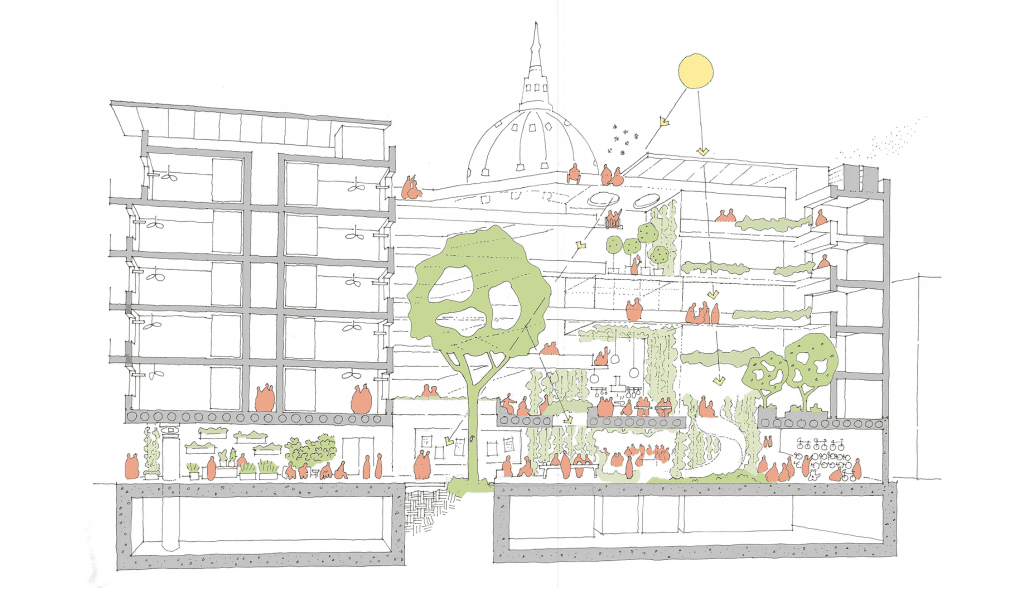

The goal is to create housing that is both beautiful and accessible. “These are units that anyone would want. This is just like any other apartment complex that you or I would be interested in renting from,” says The Kelsey’s Manager of Communications and Partnerships Eric Mondragon, adding that the building was designed with input from architect and disability advocate Erick Mikiten. “For anyone who needs a wheelchair or power chair to get around, and also for people with non-physical disabilities, we’re thinking about interior design, color choice, lighting — it’s not only people with physical disabilities but people with all disabilities.”

Upon the projects’ completion, The Kelsey plans to release a free guidebook for “Universal Design” guidelines for accessible homes.

These projects don’t come cheap, however. Kelsey Ayer Station is projected to cost $75 million, a reflection of California’s expensive housing market and the often-high cost of building accessible housing. But Mikiten argues that housing for people with disabilities shouldn’t be seen as a niche amenity for a particular group. “Universal Design is not about disability; it’s about better living for everyone,” he writes on his website.

This principle applies beyond architecture. “[For people with disabilities], the process to find a place to live as a roommate or stay as a vacationer is very difficult; it requires many more steps than for someone without a disability,” says Jeff Hinz, co-founder of Dwellability, a start-up that helps people with disabilities find roommates and vacation rentals. “A lot of times, people with disabilities have to hide their disabilities out of fear of shame and rejection, that they won’t be accepted.”

Hinz’s service, which he co founded three years ago with his wife Elizabeth who has a disability, now has over 2,500 members. Dwellability’s goal is to build a community of renters and vacationers with disabilities, and, for Hinz, “community means that there is someone in your home who knows what you need.”

Housing models like these are premised on this notion, as well as the notion that when you center the voices of people with disabilities, accessibility follows. As Mondragon put it, “Rather than speak about people with disabilities, we have to include them and let them speak for themselves. There’s no need for us to speak for them.”