In 2019, researchers from Harvard Business School, Indiana University and Georgia State University took advantage of a fortuitous court ruling to find out what happens when you get rid of student debt. A judge had ruled that National Collegiate, a company that bought up student debt and treated it as an asset, actually didn’t have a valid claim to much of that debt. So the debt was cancelled. How much? 800,000 individual loans amounting to $12 billion. A lot of students and their parents were very happy.

The researchers realized this was a golden opportunity. By tracking other graduates who lived in the same zip codes with similar amounts of debt as the lucky 800,000, they could compare the outcomes of the still-indebted control group with the suddenly debt-free students. Before this ruling, comparing students with debt to those without had always been complicated. Now it was easy.

What they found was that students whose debt was erased ended up with incomes that were 12.5 percent higher than their indebted peers in the years following graduation. Why? Not just because they had more immediate cash on hand — that difference was taken into account. The extra income often derived from changes in their behavior. The debt-free graduates could take more career risks. They were more mobile, able to move to where the higher paying jobs were. They could also pay off other debts — credit cards, car loans, mortgages — which improved their credit ratings and prevented defaults.

Removing college debt, the researchers found, improved these students’ financial outcomes in all sorts of unexpected ways. More of them got married and had kids, for example. Their improved circumstances benefit the entire economy.

The debt problem

Some 44.7 million American adults are saddled with student debt totaling $1.6 trillion. That’s more than all U.S. credit card debt combined. This didn’t happen overnight. In the 1980s, the government began to replace student grants (which are essentially gifts) with loans, shifting the financial costs of higher education to students and their parents. Meanwhile, state governments cut the budgets of state colleges. The cost of higher education in the U.S. has surged more than 500 percent since 1985. A $10,000 education 35 years ago would cost over $50,000 today. The costs are rising faster than inflation, which makes for a dicey investment.

Student debt has quadrupled in the last 15 years, leading many high school graduates to wonder if an investment in higher education is still worthwhile. For the most part, it is. With a college education, you stand to make 84 percent more money than someone with just a high school diploma. In the U.S., this gap between earnings for college grads and high school grads keeps growing, mostly because wages for high school grads are declining, and wages for college grads, even if they haven’t skyrocketed, continue to rise.

Still, as we saw, all that student debt can hold folks back well beyond college. It’s a drag on the entire economy. Eliminating it is a worthy goal, which is why there have been proposals to cancel student debt. But simply canceling it doesn’t deal with the root of the problem: the high cost of college in the U.S. Until we deal with that, the next crop of students will simply rack up huge debts all over again.

Can this be fixed? Yes, it can. If we look at other countries, many have solved the problem of crazy-expensive higher education, and by extension, the student debt problem.

Free and cheap tuition is good, but that is only part of the solution

College tends to be very affordable in Europe. Top universities are tuition-free in Finland, Norway, Denmark, Iceland, Ireland, Czech Republic, Greece and Scotland. Sweden now charges a nominal fee of E500 for undergraduates. Germany charges for graduate programs, but undergraduate education is free. Austria and France are almost free for EU citizens — they charge a few hundred Euros.

It’s not just European universities. Mexico and Brazil have extremely cheap higher education options. Argentina is tuition-free, as is Kenya, Morocco, Egypt, Uruguay and Turkey.

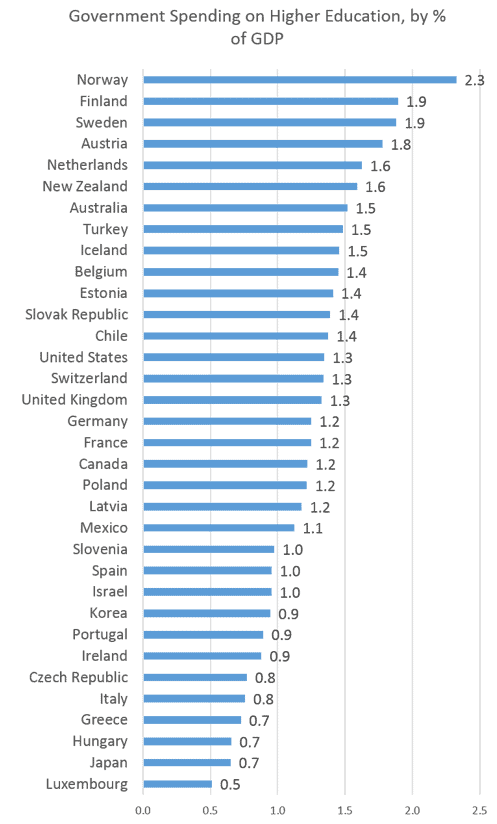

A typical American response to this might be, “Oh, those countries simply have high taxes, so that’s how they subsidize colleges.” But it’s not as simple as that. The U.S. is 73rd in the world in spending on higher education as a percentage of GDP — below Sweden, New Zealand and Norway, but ABOVE Germany, France and Canada, all of which have college options that are far more affordable. So it’s not a simple matter of tax more, spend more, problem solved.

In many cases it’s not just the tuition that is the burden, but the cost of housing and eating for four years. Some places have come up with creative approaches.

New Zealand

In New Zealand, the first year of college is free, but tuition can be as high as NZ 10,000 ($6,600 USD) a year after that. So, not exactly free at all. However, government student loans are interest-free, and students don’t have to begin paying them back until their post-graduation income rises higher than NZ 20,000 ($13,300 USD). The loans are also interest-free for as long as you stay in New Zealand. This system has allowed a lot more kids to go to college — three years after these loans were introduced in 1992, university enrollment went up 49 percent.

New Zealand also offers a Student Allowance — basically, grants to cover the cost of living expenses. Whether or not you have to pay these back depends on your parents’ income, your age and whether you are married or have a child.

Norway

Similarly, in Norway tuition is completely free, but the cost of living is high. This is a problem in the U.S., too. Part of what makes American colleges so expensive are all the extras that come with it — the dorms, the food halls, the football stadiums, the fundraising departments. And because American students often don’t live at home, add-ons like housing, food and transportation can be as expensive as tuition.

Norway solves this problem by making state loans available that can be used by students to cover living expenses. These loans are interest-free until graduation, and some students can convert up to 40 percent of them into grants that don’t have to be paid back.

Weighed down by negative news?

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.Denmark

In Denmark, tuition is free, and the cost of living is not as high, but even so there are grants to cover expenses depending on parental income. I’m seeing a pattern here.

South Korea

In South Korea, tuition is about one-third as high as in the U.S., which is still much higher than a lot of other countries. But some 18 percent of these costs are covered by private companies and foundations. I’m not sure how one prevents undue influence from corporations on the syllabus, but one hopes that the companies realize that even without influence an increase in graduates benefits them all.

Germany

The German system is unique. Early in life, kids are placed into one of three tracks: college preparatory, vocational training, or something in between. This means a lower percentage of folks go to university than in similar countries — even though it’s tuition free! This early-stage sorting means that those who do go to college tend to get masters or doctorates, while those on the vocational track get training and go into the job market. One has to make this choice early on — in high school or even earlier — which, for some of us, seems a bit young to commit to one’s life path. It’s not impossible to jump over to the university track later, but not many do.

Like in other countries, to cover the costs there are government interest-free loans for which repayment depends on post-graduation income. This model — repayment based on later income — seems to be a common and successful means of greatly reducing the burden of student debt.

Higher education as a public good?

The countries mentioned above don’t completely subsidize every higher education cost, but they have eased the burden by lowering or eliminating tuition and making loan paybacks flexible. These policies have proven successful and have lessened the crippling effects of student debt. We can learn from their examples.

We accept lots of things as public goods and happily pay for them: drinking water, fire and police departments, sewage and garbage disposal, roads and bridges. I pay for roads even though I don’t own a car because, well, that’s how my groceries get to the local store. And folks would go nuts if the fire department only served those who paid for the service, though that is actually the case in some communities.

In many countries, higher education is viewed this way, too — as a public good, a basic right. (In the U.S., that concept is wholeheartedly embraced up through high school, so the idea of education as a right does exist — it just stops short of college.) It would be unthinkable to defund grade schools and high schools (though austerity budget cuts amount to the same thing). The question is, do we accept the idea that, in the contemporary world, college might be essential as well? The bar has been raised. Education fosters resilience, which, as recent events have shown, is something the U.S. needs more than ever.