When Ukrainian refugees arrived in England earlier this year following Russia’s invasion and children started joining schools, primary teacher Anne Flude was shocked by the fanfare surrounding some of the newly enrolled pupils.

“I remember watching on the news — there was a school where they literally lined up outside with banners and were cheering on this Ukrainian refugee child. I thought ‘Oh my god, what are you doing?’ It looked overwhelming.”

In stark contrast, Flude says there was no “hoo-ha” at her school — Bourne Primary in Eastbourne, Sussex, on the south coast — when a Ukrainian child enrolled in April.

The pupil (whose gender has been withheld at the request of the school) was welcomed subtly and sensitively, and joined a class that included a recent Afghan refugee and several other new arrivals to the United Kingdom, she explains.

“We took a nurtured, child-centered approach,” she says. “The welcome was very quiet. It’s not a secret they’re a refugee from Ukraine, but it’s not like we were labeling them as this or that, you know? They’re just a child.”

Bourne Primary’s attitude is perhaps unsurprising given its ethnic diversity — more than 34 languages are spoken among its pupils — and the fact it has recently been designated a School of Sanctuary.

More than 360 schools in the UK have earned the recognition (or award, as it’s known) by demonstrating they can provide a welcoming and inclusive learning environment for those seeking refuge in the United Kingdom, teach pupils about migrants and refugees, and engage with the local community.

The City of Sanctuary charity started the Schools of Sanctuary program in 2010, and education experts say today the initiative is a rare source of reliable information and continuous guidance at a time when more people are seeking asylum in the UK and government oversight and support for schools is in short supply.

To receive the designation, schools work to meet eight criteria with mentoring support from Schools of Sanctuary throughout the accreditation process. The criteria include training staff on refugee and migration issues and incorporating these topics into the curriculum, participating in events such as the annual Refugee Week, and publicly sharing activities and best practices in pursuit of the award. The Schools of Sanctuary team promotes everyone in the network, and encourages them to join national campaigns and share their experiences and advice. The schools are reaccredited every three years to ensure they maintain high standards.

In the case of Bourne Primary, Flude says that becoming a School of Sanctuary had spurred it to learn more about refugee and migrant issues — from drivers and dynamics to terminology — and focus more on therapy and therapeutic thinking. All staff are going to be trained on how to provide trauma-informed care, she adds.

Extended learning

There are currently 300 or so schools signed up to go through the Schools of Sanctuary process. There has been an unprecedented surge in interest over the last year since the UK launched the Afghan Citizens Resettlement Scheme and the Homes for Ukraine initiative.

With refugees settling in communities where there is little diversity or experience of asylum-seekers, schools are scrambling to ensure they are ready to integrate such children, says Megan Greenwood, coordinator at Schools of Sanctuary.

“More schools are looking for support,” she says. “We are getting emails saying: ‘We’ve got six Ukrainian children arriving next week. What do we do?’”

Government data from August showed that 16,200 school places were offered to children from Ukraine and 6,900 given to Afghan pupils in 2021–2022.

Greenwood says that amid a lack of government guidance in England, schools must consider various factors such as their admissions system, additional support for new families, and staff training — be it on teaching English as an additional language or trauma-informed care.

But it’s not just about welcoming new arrivals.

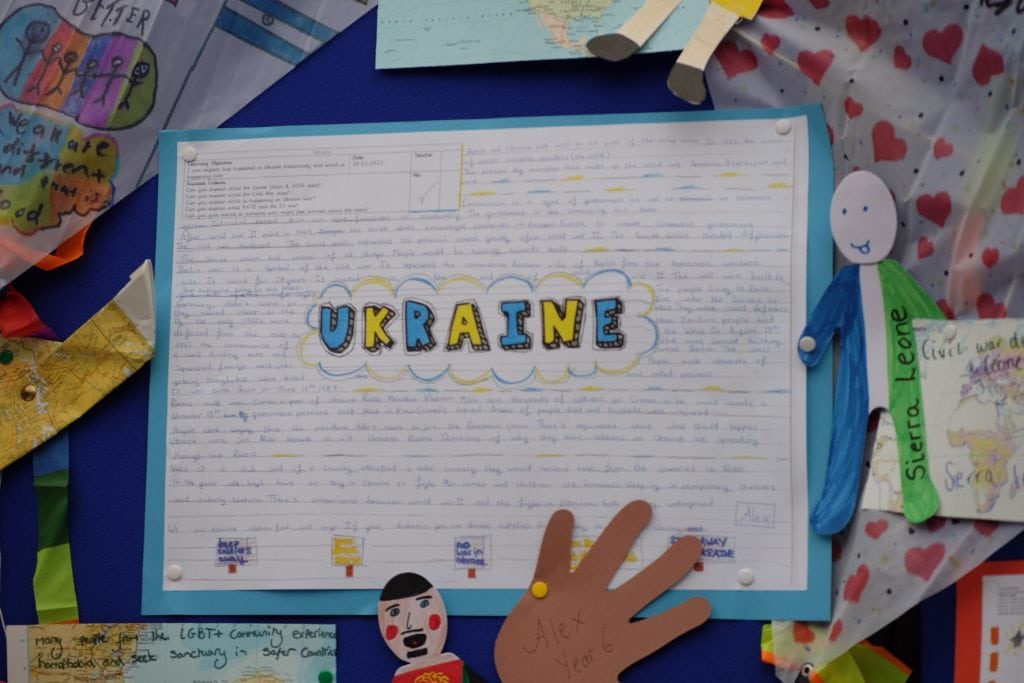

Wood Ley Primary became a School of Sanctuary in June despite the fact it has no refugee or asylum-seeking children and is located in Suffolk, a region northeast of London where the population is predominantly white and British.

That has not stopped the school educating its children and raising awareness about migration and multiculturalism for several years. It has introduced play and drawing therapy, ensured its library has books featuring refugees, and written the topic into its curriculum — ranging from the plight of Yazidis fleeing Iraq to broader themes including the dangers for LGBTQ+ asylum-seekers abroad.

Wood Ley Primary also gets involved with the wider community. They’ve invited parents from nations such as Romania and Turkey to read for the children and teach them to cook. They collected essentials for refugees including Afghans who have arrived in the area, according to assistant headteacher Jasmine Kay.

The importance of community engagement is understood all too well at Chandos Primary in the multicultural central English city of Birmingham, a School of Sanctuary since 2019.

Unlike Wood Ley Primary, it has an extremely diverse population — and also a mobile one, with more than 100 pupils having left the school and another 100 or so having joined in the last academic year, between 10 and 20 percent of whom were new to the UK.

Weighed down by negative news?

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.Chandos Primary has a staffer who not only teaches English as a second language to pupils but also helps their parents to learn, and a support worker who helps new families to access services such as healthcare and even apply for asylum.

While highlighting the diversity of the school — including nationalities as varied as Afghan, Bangladeshi, Somali and Yemeni — headteacher James Allan says it had to be “careful” and “sensitive” in terms of discussing current events and even with its admissions process.

For example, Chandos Primary has received enquiries about the possibility of enrolling one or two Ukrainian children but the situation is complicated by the fact there are already well-established Russian families at the school, he says.

“It’s a very, very fine balance,” Allan explains.

While the school does not specifically teach about conflicts like those in Ukraine and Syria, discussions will often arise in the classroom — especially among older pupils who may hear or read about such issues on the news.

“We need to be very careful to manage those opinions,” he adds. “Because in a school like ours, they could very quickly result in an avoidable sort of confrontation, whether it’s between children or families. And our ethos is very much about being open, tolerant and welcoming.”

Another challenge for Chandos Primary is the feasibility of continuing to provide wraparound care, including second-hand uniforms, weekly food parcels and home visits, as the cost of living crisis bites.

“There’s a greater need for family support than there ever was before, schools are not just places to be educated now,” Allan says. “But to provide that takes a chunk out of my budget, I don’t get extra money for it. That dilemma is always there, but it’s growing significantly.”

A welcoming community

As schools face ever-growing pressures, refugee and asylum-seeking children are struggling to access education and the necessary support — from English provision to psychosocial support — once enrolled, experts and campaigners warn.

Local authorities have a 20-school-day government target to offer education to unaccompanied asylum-seeking children under their care.

However, Catherine Gladwell, chief executive of the charity Refugee Education UK, says some young people arriving in the UK were waiting for six months — or even up to a year in certain cases — for a place in school.

Factors include long waiting lists, complicated online application processes, time-consuming identity checks, a lack of expertise in local authorities, and the fact many children are initially placed in temporary accommodation.

Furthermore, some schools, especially academies that operate independently from local authorities, are reluctant to receive refugee children due to concerns about funding and academic results, according to Gladwell. While local authorities can direct regular schools to take a child, only the UK’s education minister can order academies to do so — a lengthy process that compounds such delays.

“The crises in Afghanistan and in Ukraine are a kind of a magnifying glass on the challenges that refugee and asylum-seeking children have faced integrating into education,” she says, praising Schools of Sanctuary for providing a critical sense of welcome in the community.

While Greenwood of Schools of Sanctuary was enthused by the soaring interest and participation, she says it was “slightly daunting” given its small team to support, vet and promote schools.

The initiative used to receive funding purely from City of Sanctuary, but this year gained some financial support from the Malala Fund, the non-profit co-founded by Malala Yousafzai, the Pakistani campaigner for girls’ education and Nobel Peace Prize laureate. And while the award is free, some schools in the network have started contributing, too, and “every single donation counts,” Greenwood says.

Amid such challenges and concerns, Greenwood says the work feels worthwhile and that she is inspired by many of the schools in the network.

Schools such as Wood Ley Primary and Lochardil Primary in Inverness — which in July became the first in Scotland to be awarded — deserve credit, she says, because they were so proactive and prepared to receive refugees despite having had none in their communities.

In the latter’s case, Ukrainian families have recently arrived into the local area, heard about Lochardil Primary’s efforts, and want their children to enroll, Greenwood explains.

Several schools have shown an interest in the award because they also want the children within their communities to understand the reality of migration and why people seek refuge in the UK, and not be misled by negative news headlines or myths and misinformation online, she adds.

Kay of Wood Ley Primary says “most schools in our situation would think that the award doesn’t apply to them.”

“The majority of our pupils are white British … and therefore we want to bring representation and diversity to them,” says Kay, who has previously taught in refugee camps in France and Greece. “It’s just as important if not more important, because we don’t want to have a hostile environment or prejudice towards people of different nationalities and different cultures.”