Marco Wendt still remembers the first time a condor egg moved in his hand. “I was scheduled for the overnight shift to observe the egg,” says the bird expert while four massive adult condors doze before him on “Condor Ridge” in the San Diego Zoo Safari Park. That night, he was holding the palm-sized whitish egg in his hand when he heard a sound. “Then the tiniest crack appeared,” he remembers with a grin, “and I was so fearful, handling it with the greatest care.”

Every condor egg is uniquely precious because these giant vultures usually only produce one egg every other year. As Wendt explains, “If this egg is lost to a predator or not fertilized, it affects the entire population because we lose a whole year.”

Historically, thousands of California condors soared through the skies, ranging from British Columbia to Baja California. Fossil records indicate that these birds once even inhabited present-day Florida and New York. “The condor is a keystone species,” Wendt says, pointing to the emblem of the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance that features condor wings next to a lion. “They are the largest flying birds in North America, with a wingspan of up to 10 feet.” The Inca believed the condors brought back the souls of the deceased. Indigenous tribes traditionally held the condors in high esteem, viewing them as a symbol of power, not only because of their massive wings and soaring power but also because of their keen intelligence.

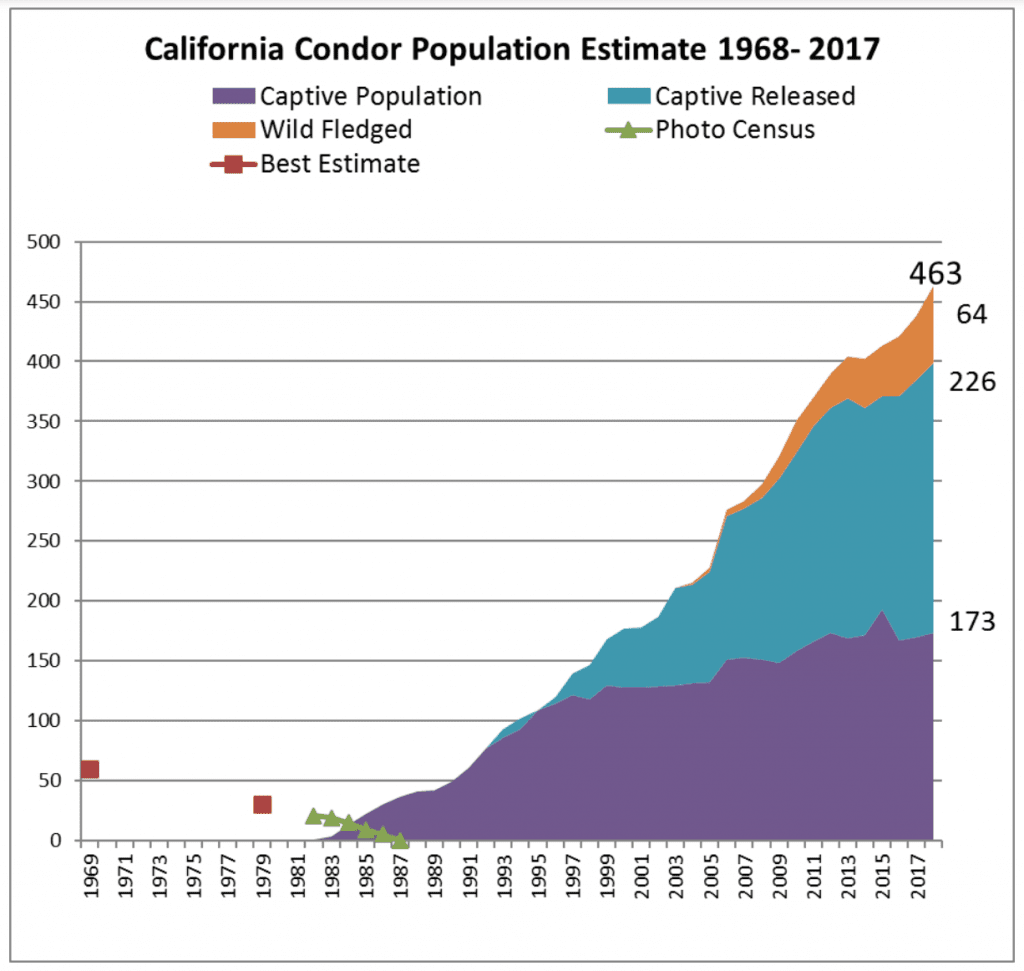

But by the time Wendt was born in 1982, only 22 remained. In 1986, the US Fish and Wildlife Service took drastic, controversial action: they captured all remaining condors from the wild to save them.

Now 537 Gymnogyps californianus soar over North America again, 334 of them in the wild, with their characteristic rumbling wing swoosh that earned them the nickname “thunderbird.” The iconic birds are slowly expanding their range again, from Big Sur to Arizona and Baja California, not least thanks to Wendt and his employer, the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance. This year, 11 eggs have been laid at the “Condor-minium,” as Wendt and his colleagues playfully call the breeding station, a large facility in a quiet part of the 1,800-acre safari park where no visitors are allowed.

Tecuya, the old condor gal in front of us on “Condor Ridge,” is asleep on the branch of a desert Mesquite tree next to a Bighorn Sheep. When she awakes, she stretches her bald head and her massive four-foot wings into the sun — older condors are recognizable by their characteristic pink heads. Those of the younger ones, like Eva next to her, are dark black. Eva was rescued from Big Sur at four months old after her mother died of lead poisoning and her nest was threatened by a wildfire — unfortunately a typical condor biography.

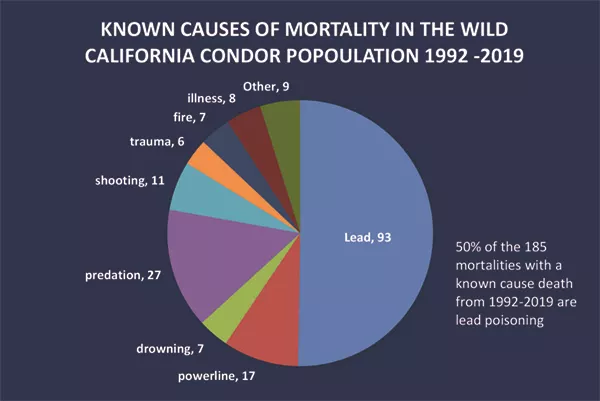

The main reason condors were decimated to near extinction was not just urban encroachment on their territory, power-line collisions and egg poaching. Though these birds don’t have natural enemies, rodenticide and environmental toxins, especially DDT, cut many condors’ lives short. So does lead — because they are scavengers that feed mostly on dead animals, the bullets in killed deer, elk or rabbits can poison them.

DDT is not deadly to them but it leads to thinning of the eggshells and impacts the condors’ fertility. And the condors might feed glass shards or metal bottle caps from the innards of the carcasses to their young, mistaking them for healthy bone fragments.

By taking all condors into captivity, conservationists protected them from these environmental hazards. In 1988, the first healthy condor chick, Molloko, was born in captivity. “The original number one is still here,” Wendt says of Molloko affectionately. “He’s a super daddy, producing California condors every year.” Most of his 31 chicks have been released into the wild.

Condors live up to 60 years. Like many long-lived animals, they develop slowly, not reaching their full plumage and sexual maturity until they’re six years old. And because the females usually only lay a single egg every other year, caretakers have learned to “double-clutch” them: They immediately take the first egg away and put it in an incubator, which often prompts the mom to produce a second egg. The parents are then allowed to raise that chick, or if the second egg is not fertilized, they will get the first chick back.

Wendt imitates the hissing, grunting sounds the condors make, as he has learned to communicate with them. Growing up, he was mesmerized by The Jungle Book and fascinated by wildlife, “but the one thing I didn’t like about The Jungle Book is that vultures are always portrayed as negative, as evil, just waiting for someone to die.” In reality, he has learned in his nearly 20 years at San Diego Zoo that “they fulfill many essential roles in the ecosystem because they are the cleaning crew. For instance, they prevent the spreading of diseases. Did you know that they can digest dead animals that have been infected with rabies without getting or spreading the disease themselves?”

Asked what surprised him most in observing the condors, he describes their tenderness. “They can easily rip open the thick skin of a whale carcass with their big beaks but, at the same time, they can be so delicate with their chicks.”

As proof, he points to the gray baby condor feather tied to his sand-colored safari hat: “This is from Suyana,” he says proudly, “one of the first Andean condor chicks I raised.” When he was gone for a year from the zoo, he didn’t expect her to still recognize him but he fondly remembers that as soon as he returned “she came running to me, excitedly flapping her wings.”

For exactly this reason — because the birds imprint on humans — only those that don’t have a chance to live in the wild are allowed to interact with humans at the zoo. As a result, zookeepers at the Condor-minum are usually found peeking through one-way windows or cameras into the nests inside so they can’t be seen. Even the caretakers don’t show their faces to the chicks that are destined to be released into the wild. If any of the hatchlings need additional feeding, Wendt and his colleagues will put condor-shaped “puppets” over their hands to feed the young.

This was a lesson the zoo learned the hard way. When the first condors were released from captivity, they loved humans too much. They fearlessly approached people, expecting to be fed. However, raising orphans just with puppets was not successful either. Condors are extremely social and rely on an intricate interfamily network. The young who hadn’t learned from their elders flew into power lines, tore apart yards and didn’t know how to find food. So now, adult condor “mentors” train orphans before they are released into the wild.

“It was a learning curve,” Wendt admits. The San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance has become legendary for pioneered new approaches to wildlife conservation, collaborating with specialists worldwide. It has helped reintroduce more than 44 endangered species into native habitats, many of which were born at the zoo, the safari park or one of the five conservation stations it manages. It also includes a Wildlife Biodiversity Bank, a resource for cells and samples to help bring back species from the brink of extinction, including the Northern white rhino, gorillas and leopards.

Over the course of the last two decades, behavioral experts like Wendt have discovered surprising new facts about condors. For instance, although they usually mate for life, genetic testing of the more than 900 condors born since their near-extinction in the ‘80s has enabled the bird experts to determine which offspring has which parents, leading to the discovery that condors have extramarital affairs. They might even live in polygamy and raise chicks as a trio.

And because the male and female birds are visually indistinguishable, the experts rely on genetic tests to figure out which pairs can mate. Recently, the San Diego Zoo discovered for the first time that two eggs were fertilized without a male. Both chicks were biologically fatherless, a previously unknown instance of asexual reproduction through parthenogenesis that Wendt calls “mind-boggling.” It had been observed before with a few other birds in the wild when no mate was available, but never with California condors, and the zookeepers found it especially surprising because two fertile males had been housed with the moms in the zoo. Did the girls simply not swipe right? “We are making jokes about the situation,” Wendt says, “but the truth is, we simply don’t know. We are still learning new things about the condors all the time.”

The main reason for the extensive testing is to ensure the condors’ survival. Under the guidance of the US Fish and Wildlife Service, chicks are carefully selected to be released in five areas between Big Sur and Mexico where their genetic lines are most needed. Increasing gene diversity from the bottleneck of 22 required a complex process of selecting and breeding the best-suited birds. The geneticists have identified 13 distinct genetic lines from the original 22 and carefully select mates based on family lineage to further the birds’ long-term survival. Any chick’s death by poisoning or wildfire might shift the fluid calculations of which lineages need more or fewer offspring.

The other chicks remain in zoos, where they continue to be part of breeding programs and represent their species. “It’s important to have them as ambassadors here,” Wendt says. “When guests actually see the face of an animal, when they hear the wind as the condors are pumping their wings, they connect with the wildlife a lot more.”

Tiana Williams Claussen, a member of the Yurok Nation and director of the Yurok Tribe Wildlife Department, was instrumental in sharing her ancestors’ knowledge of the birds and creating the Yurok Tribe Wildlife Program. A Harvard-educated biochemist, she spearheads the effort to reintroduce California condors to the Yurok territories, which include the Klamath Basin in Northern California, by evaluating the condors’ needs and environmental contaminants. She is uniquely equipped to balance the spiritual and scientific understanding of wildlife, especially the condor, as the Yurok Nation determined its return to be of uttermost importance.

“As Yurok, we believe the condor is one of the highest animals because they are considered very strong, kind-hearted and powerful spiritual beings,” she has said. “They fly higher than any other animal in our region, and so we figured they get our prayers to heaven when we are asking for the world to be in balance. We are taught condors are never to be harmed, and any feather we might find is a gift.”

When the condors were locally extinct well over a hundred years ago, “there [was] a very deep ecological and cultural hole in the Yurok world,” Claussen added. “Now the condor is coming home.”

The Yurok Tribe joined the collaborative conservation efforts in 2009 and, in March of this year, after 15 years of working toward this goal, it has for the first time released four captive-bred condors in its territory. Now the “prey-go-neesh,” as the Yurok call them, fly again over the redwoods that were once their territory. The Yurok aptly named one of the first condors “Nes-kwe-chokw,” which means, “He returns.”

The vision is to restore the condors to their original range and see them soar again from British Columbia to Mexico, both as an essential ecological cleanup crew and as a spiritual symbol of renewal — hopefully without human intervention.

Tecuya spreads her wings again and nods her pink head.

Image credits: Gregory “Slobirdr” Smith/Flickr; San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance; Shutterstock; US Fish and Wildlife Service