When Florence, the principal of a rural elementary school in Eastern France, heard about the suggestion to install white mailboxes for her students, she thought it was a neat idea. The children could write about anything that weighs on them, initiator Laurent Boyet explained to the kids, and a professional team of psychologists, doctors, educators and law enforcement would then confidentially work to find solutions. Boyet would install a white mailbox in the school cafeteria to collect their letters, which would be read every day.

“It seemed interesting,” Florence (who requested only her first name be used to protect her students’ identities) told the Associated Press. “I thought there were not many issues in my school so, at the beginning, it was more to clear my conscience. I thought it wouldn’t hurt. As it turns out, there were some needs.”

The mailbox was installed on a Friday morning last June, and on the very first day, a 10-year-old girl submitted a letter, in which she said that her grandfather inserted his “lower part” into her “lower part.”

“We got the letter at noon,” Boyet says via Zoom from his home in the South of France. “By 4 o’clock in the afternoon, we had a plan.” On the following Tuesday, a trained psychologist spoke with the girl and learned that her grandfather had not only raped her, but also two cousins. “He was arrested on Wednesday,” Boyet says. “It took exactly five days between receiving the letter and arresting the perpetrator.” The man is still in prison, awaiting trial.

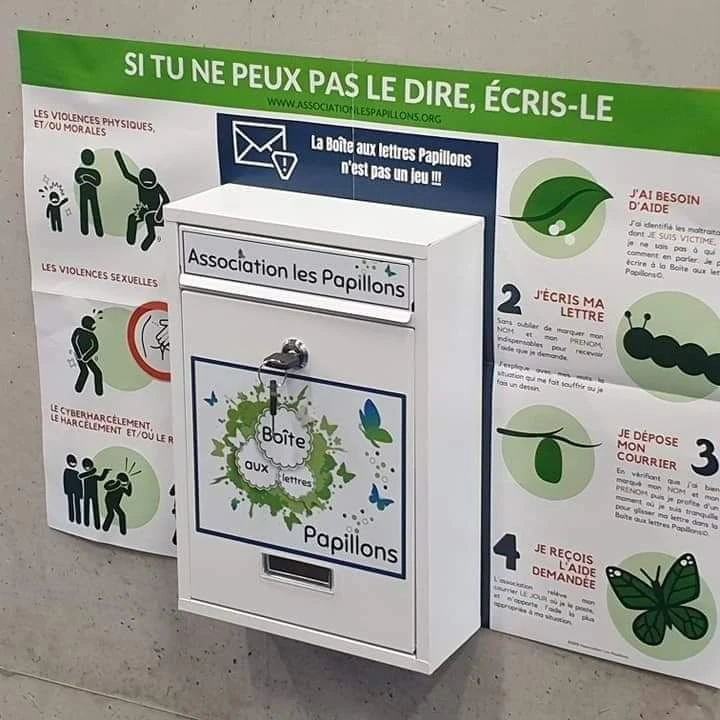

Boyet is a police station captain in the idyllic tourist town of Perpignan in the South of France. Since spring 2020, he and his team have installed more than 220 white mailboxes in schools and sport clubs all over France through his nonprofit Association Les Papillons, “The Butterflies.” More than 60,000 children have access to these mailboxes, and the team has received more than 2,000 letters thus far. Boyet’s motivation is more personal than professional.

“My older brother started raping me when I was six years old,” 49-year-old Boyet says. “The abuse lasted three years and I had absolutely nobody I could confide in.” His brother, who was 10 years older, threatened to kill him if he told anybody. Instead, Boyet wrote down what happened in notebooks. It took more than 30 years before he found the courage to speak about the violence. “My family reacted like most families react: They disowned me and broke off contact.” His late mother said she believed him because she had some suspicions during his childhood, but his three sisters decided not to speak with him anymore. In 2017, Boyet published a memoir titled All Brothers Do This, one of the phrases his brother used to say to him to keep him quiet.

What gnaws on Boyet is the number of unreported cases. Boyet estimates more than 165,000 children are violated in France every year. “One child every three minutes, two children in every classroom,” Boyet says to illustrate the fates behind the numbers. But experts agree that the dark figure is a lot higher. According to the World Health Organization, every fifth girl and every thirteenth boy has been sexually abused before turning 18. “And most children don’t dare to talk about it,” Boyet says, “like me back then.”

Hence there’s the motto on every one of his mailboxes: “If you can’t say it, write it.” Before he and his team install a butterfly mailbox, they visit the school or club to introduce themselves and their project and also to encourage the children to sign the letters with their names so they can be helped.

Thirteen percent of the letters that reach his team are about bullying at school; 21 percent write about physical abuse and seven percent about sexual violence. Thirty percent of the violence disclosed in the letters happens within the family, and 70 percent concerns girls, Boyet has found. Only two percent of the letters are trolling the project. “If we’re not sure, we’ll look into it,” Boyet says. “We’d rather fall for a prank than overlook a child in need.”

Boyet is working with mayors and communities throughout France to build a network in every district, “so that the children learn that there are adults they can trust.” When children write about bullying or other violent incidents at school, trained educators will intervene. “Through the letters we continue to learn whether the problem persists or has been solved.”

Eight- and nine-year-olds write more than half of the letters, and 15 percent come from six- and seven-year-olds. “These are exactly the children I want to reach the most,” Boyet says, and not only because of his own biography. “France has a national hotline for child abuse but children under nine years usually don’t have a mobile phone yet and it is not easy for them to call someone without being noticed. But any child can write a letter.”

Some draw. Recently, a child in Toulon, a small city in the South of France, submitted a letter with a drawing. It showed a bright orange flash directed from the lower abdomen of an adult to the lower body parts of a child. “We immediately investigated,” Boyet says, and this turned out to be another case where his team could save a child from acute danger and prevent further abuse. About five percent of letters indicate serious violence that calls for the involvement of law enforcement, according to Boyet, and two percent are from children in immediate danger.

“The best part of this project is that children can write in their own words, unfiltered and without adult interference,” Boyet says.

The nonprofit’s name was inspired by a girl named Lily. She had been abused by her grandfather at the age of four, and talked about how much she loves butterflies because they are so colorful and fly free. “Butterflies are part of the imagery world of children,” Boyet says. “The image immediately spoke to me so much that I named our organization Les Papillons.”

In addition to installing mailboxes in more schools, Boyet is actively lobbying to change French laws. For instance, he’d like the country to abolish the statute of limitations for child abuse because many victims can’t speak about the abuse until decades later, like he did. He is also working to build a “Butterfly House,” a shelter where abused children can heal from traumatic experiences. “It’s a big project,” he admits, “but we can’t pretend child abuse isn’t happening. We have to find solutions.”

He continues to do what he wished someone would have done for him when he was six years old.