When Suganthine Sundaralingam goes door knocking in her community in Scarborough, Toronto, she carries two folders with her: one with flyers in English listing the nearest vaccination pop-up clinic at the Dorset Park Community Hub, the other carrying the same flyers in Arabic, Cantonese, Spanish, Tamil, Urdu, Farsi and Tagalog.

As a neighborhood ambassador for the Scarborough Center for Healthy Communities, Sundaralingam is able to sign people up without inputting OHIP information, enabling undocumented people and migrant workers to access the vaccine. She’s kept a spreadsheet of the 100 people she’s registered for vaccine appointments since the start of May — relatives and members of the language circle she hosts in her building, families of her son’s schoolmates, visitors to the garden where she volunteers and residents of her building, where she’s part of the neighborhood association.

Sundaralingam moved to the Toronto Community Housing Corporation building she now lives in 13 years ago, after separating from her husband, and has been advocating for her community ever since. After learning that the nearest English class for newcomers was two bus rides away, she helped form the Women’s English Circle, an informal group to learn English and nurture social relationships between immigrant women. She will proudly tell you it was the first program to be hosted at the Hub when it first opened in 2011. Sundaralingam’s ties to her community run deep.

The neighborhood ambassador program is designed to identify people like Sundaralingam to conduct vaccine outreach. It is a function of the City of Toronto’s Vaccine Engagement Teams Grant which focuses on 140 neighborhoods, with an emphasis on hard-hit regions. Lead organizations, such as the Scarborough Center for Healthy Communities, form partnerships with community agencies and, more specifically, resident-led grassroots groups to hire and train ambassadors. The main criteria for ambassadors is sharing the lived experience of community members made most vulnerable through the pandemic. At least $5.5 million has been awarded across the 140 neighborhoods.

Throughout the vaccine rollout, these ambassadors have played an outsized role behind the scenes. They’ve found elders, people with precarious status unhoused people, and other groups who could not refresh their browsers at the precise second a vaccine appointment became available. Their on-the-ground efforts, which often involve identifying their community’s barriers to access and advocating for their needs, have carved a pathway to the vaccine that had largely been overlooked by the government until recently.

The need for community ambassadors was evident long before the vaccine rollout began. At the beginning of last October, when Covid testing sites at downtown hospitals saw long lines that circled street corners, testing rates among the worst-affected neighborhoods were far below the rest of the city. In response, the province allocated $12.5 million dollars in funding towards neighborhood ambassadors to increase testing and access to wraparound support in 15 high priority communities. Drawing on the local knowledge of ambassadors and the community agencies that employed them, a number of pop-up testing sites were established in pockets of the city underserved by previous efforts.

“It took the system a really long time to figure out that actually, the lack of testing in the highest transmission communities was an economic situation,” says Sophia Ikura, executive director of the Health Commons Solutions Lab. “But the community ambassadors knew right away.”

The Rexdale Community Health Center (RCHC) was one of the first lead organizations to receive funding from the city, in April 2021, though they began their outreach well before. Yet, it was only this month that they noticed a marked difference in the people visiting their pop-up clinics. Suddenly, they were seeing more people from North-Etobicoke, an area with disproportionate Covid spread, as opposed to the crowds of people coming from other parts of the Greater Toronto Area.

Terrence Rodriguez, Covid engagement team coordinator at the RCHC, attributes that change to the five neighborhood ambassadors they were able to hire through the program. “Ever since we started, the most common way people heard about our pop-up clinic has been word-of-mouth” he says. “We even contacted the fire department to see if we could make announcements over the PA system in buildings.”

“The challenging part is managing the hours,” says Rodriguez. “The ambassadors also help with the vaccine clinics, line management, they’re undergoing training — that eats up time.” Across the 10 community and resident-led groups allotted funding within North-Etobicoke, neighborhood ambassadors range from two to nine individuals, each group dividing up the hours to suit their airtight budget. “Initially when we looked at what we wanted to do and what we needed to do, we surpassed the budget by three times what we were allotted,” says Rodriguez. “We had to really scale down.”

Weighed down by negative news?

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.As the province plays catch-up and implements services to improve access to the vaccine following a disordered rollout, community ambassadors are an integral conduit between shifting systems. When Sundaralingam registered her 86-year-old non-English speaking relative for the vaccine, she consulted Toronto Ride to arrange transportation. As a senior, her relative is eligible for a free ride to and from her residence to the vaccination clinic as part of the recently developed “vaccine equity transportation plan;” however, the service requires 72-hours notice. When Sundaralingam was only able to confirm her relative’s appointment 48-hours in advance, a Toronto Ride administrator noticed the short travel distance and asked: “Why can’t she just take an Uber?”

Frustrated with their response, Sundaralingam insisted her relative was a senior and qualified for the free service, yet resolved she would find alternative transportation. Later on, Toronto Ride phoned her relative instead of connecting to Sundaralingam when transportation became available. When the relative heard someone mention the vaccine, she repeated the only word that made sense: “Covid-19.” The administrator assumed she was facing Covid-related complications and called an ambulance to her house. In this comedy of errors, Sundaralingam is a throughline that would have saved resources and improved outcomes.

It is these touchpoints between care that ensure survival. Ikura believes the success of the neighborhood ambassador program is due to the quality of lived experience that enables community members to acutely understand and advocate for the needs of their neighborhood. “It’s an excellent case study for how in a very short period of time, we can find those individuals, activate them with training, set them up in the community and deliver the results that the largest system has not been able to produce,” she says.

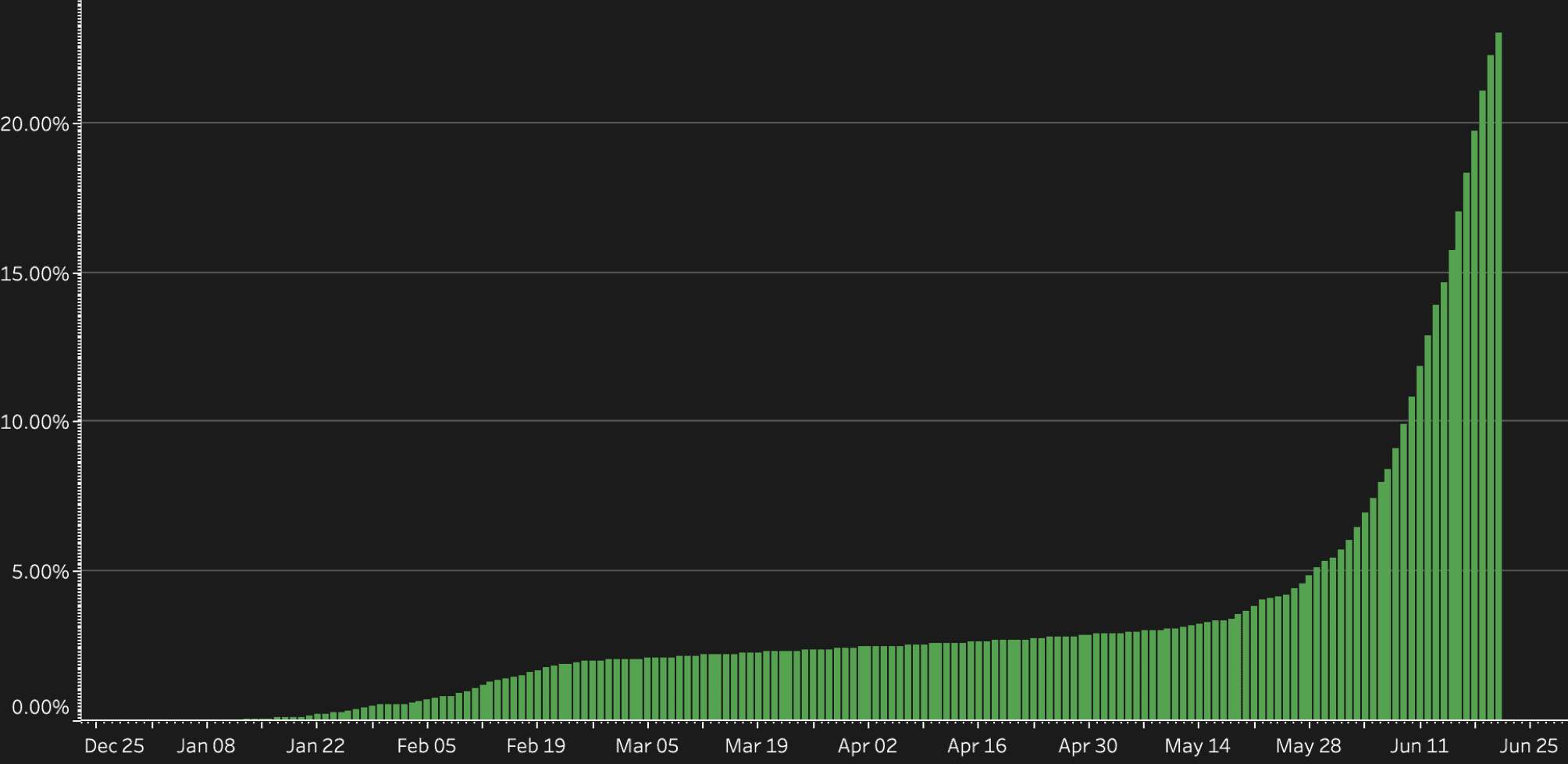

Presently, Toronto is racing towards mass immunity, with 70 percent of Toronto adults having had at least one dose of the vaccine. But in this rush to return to normal, the remaining 30 percent of people must be remembered. If we don’t pay attention to their specific vulnerabilities, Ikura envisions a pattern similar to what happened with testing and vaccine distribution recurring. “We’ll hit a 70 percent vaccination rate, the province will pat themselves on the back, and then Covid will start to spread again,” she says. “Because we didn’t get to the places where people are at risk.”

In order to reach these places, people who share and understand the experiences of the community are vital — people like Sundaralingam, who plans to give flyers to elders who require at-home vaccinations in her building. “I know where to go,” she says.

This story was originally published by The Local. It is part of the SoJo Exchange from the Solutions Journalism Network, a nonprofit organization dedicated to rigorous reporting about responses to social problems.