Welcome back to The Fixer, our weekly briefing of problem-solving efforts and initiatives reported in publications around the world. In this week’s edition: Can foggy days quench the world’s thirst? Plus, a program to help senior citizens adjust to life after prison, and a country that wants to squash malaria—but not mosquitoes.

Net Worth

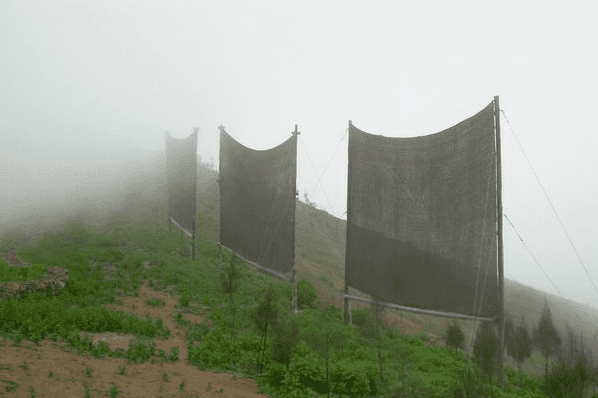

We pull drinking water from rivers, lakes, deep underground, even the ocean. People living in mist-draped coastal areas pull water from fog, too. They use a contraption called a fog harvester, which is basically a net that captures water droplets on the breeze and uses gravity to funnel them into a container. It’s a simple, elegant tool that does what tree needles have been doing since time began. (California’s redwoods get one-third of the water they drink from the region’s fog.)

Now some scientists are looking for ways to make fog harvesters more efficient. One prototype is called a fog harp, which eliminates the net’s horizontal strings so the water can cascade more easily. Another device, developed by MIT researchers, uses electrodes to give passing water droplets an electrical charge, which attracts more fog to the mesh.

Fog harvesters have largely been seen as coastal solutions, but one location where they hold enormous potential is power plants, which use huge amounts of water for cooling purposes. All those plumes of steam you see rising from power plant cooling towers is purified water, just waiting to be caught in a net and hauled back to earth.

Respect Your Elders

Imagine going to jail in your twenties or thirties and, decades later, stepping into a world of smartphones, debit cards and strange new social norms. For the long-term incarcerated, this is the reality of re-entry. To smooth their transition, the Bay Area’s Senior Ex-Offenders Program (SEOP) addresses the needs of senior citizens recently released from custody.

Those needs are unique—older people released from custody have lower than average recidivism rates, but higher rates of homelessness, loneliness, medical problems and unemployment. SEOP focuses on these. It connects clients with doctors who specialize in health concerns exacerbated by prison life. (Consider the arthritis sufferer assigned to a top bunk for years.) Case workers help them update long-expired state IDs and credit cards, and bring them up to date on everyday perils like hackers and phishing scams.

SEOP also maintains inroads with workplaces that are a good fit for seniors, such as janitorial companies where the work doesn’t require too much heavy lifting. And housing is of particular concern in the region’s pricey real estate market, so the group manages three transitional homes that its clients can stay in until they find their own place.

The data on long-term outcomes is scant, but demand for the program is high: it has received 4,000 applications for residency in its transitional housing since 2016. And clients like the vibe. “There’s no forced treatment here,” says one. “If you want to get a job, or go to school and get a degree… they support you in what you are doing… And if you’re about to crash and burn, they step in.”

A Bug’s Life

Not long ago, malaria in Bhutan was a serious problem. At its peak in 1994, the country had 40,000 cases. Last year? A whopping 54. This shift is all the more remarkable when you consider an unusual aspect of life in Bhutan: They don’t like to kill animals — not even mosquitoes, the primary vectors of the disease.

So when formulating its approach to the issue, the government had to take into account the Buddhist belief that all life, including bug life, has inherent value. Whereas many countries control malaria mainly with insecticides, Bhutan has instead focused on getting its diagnosis and treatment numbers up. It has also pursued poverty reduction aggressively, in part because people with higher incomes have less contact with mosquitoes. Where insecticide is used, authorities have made efforts to meet skeptical citizens halfway. One entomologist says he reframes the process as a distinctly Buddhist live-and-let-live proposition: “We’re just spraying the house,” he tells residents. “If a mosquito wants to commit suicide by coming in, let it.”

Since the effort began 25 years ago, infections have fallen by 97 percent, saving thousands of lives. It may be the tiny kingdom’s second-most impressive statistic.