This story was originally published in the Daily Yonder.

Tucked away on a quiet side street in downtown Bennington, Vermont, is the public library. It’s an imposing brick building, remodeled in the 1930s to mirror a 19th century courthouse with huge arched windows that bathe the interior in natural light, even in the gloom of Vermont’s long winter days. Recently, it’s been troubled by a very 21st century problem.

The police arrived first, responding to a 911 call from library staff. A man lay unconscious in a bathroom stall, still and unresponsive. With the cubicle locked, an officer squeezed under the metal door enough to drag the 45-year-old, who by then had turned deathly purple, onto the bathroom floor. It was the second library overdose in six months.

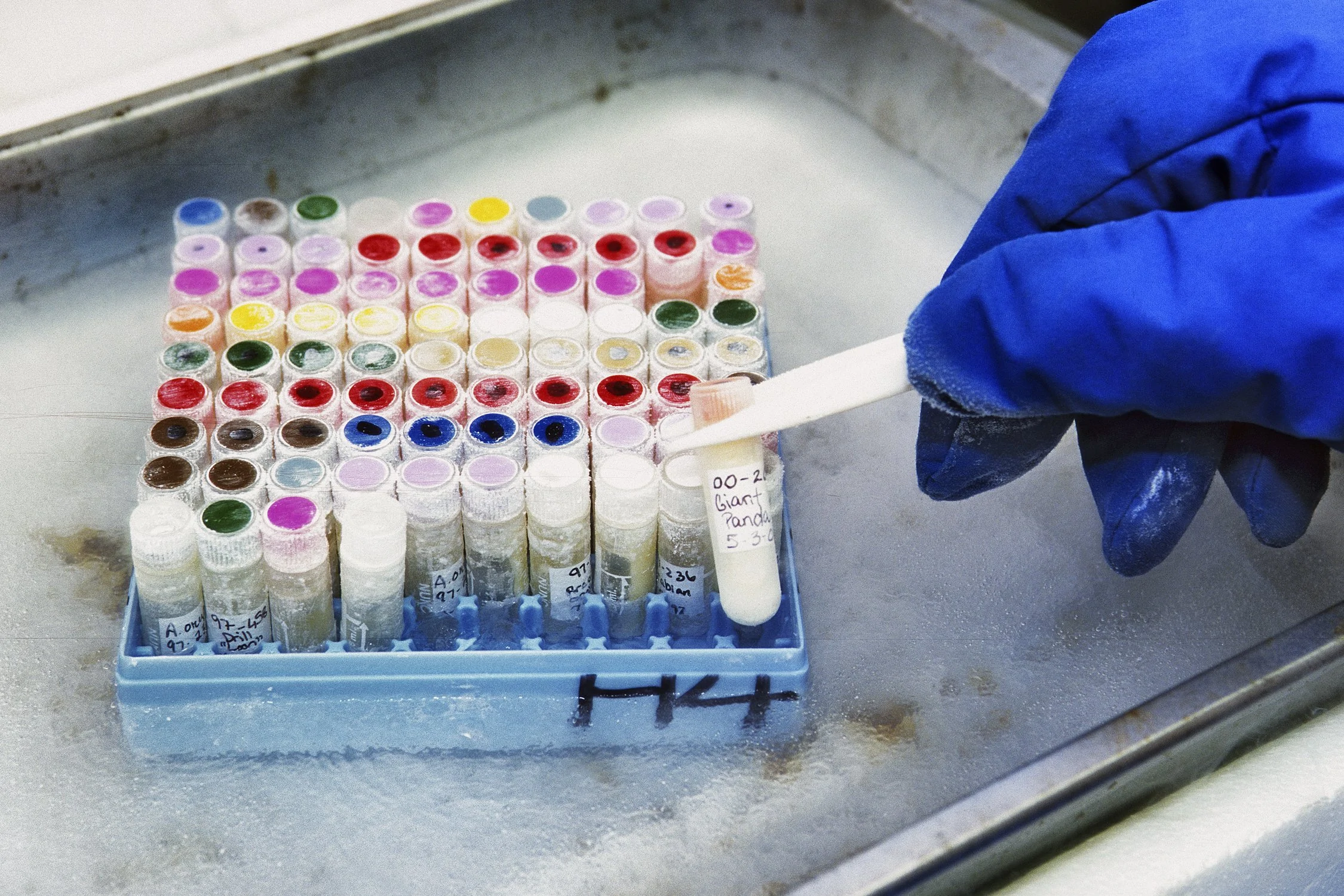

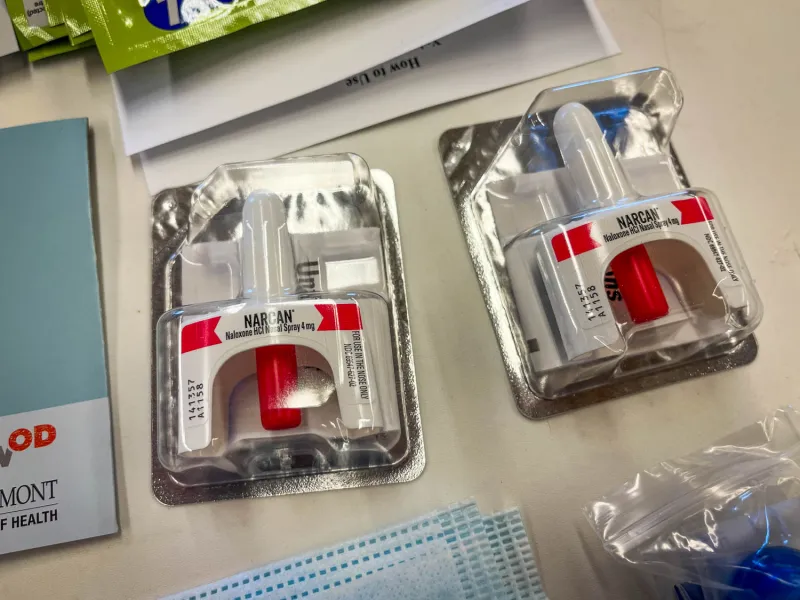

Within seconds, an officer had forced naloxone nasal spray, an opioid overdose treatment often known by its brand name Narcan, into the victim’s nose. As his color returned, his eyes shot open. Agitated but revived, he nervously admitted to injecting fentanyl but refused an ambulance to the local hospital.

Emergency Medical Technicians (EMTs) are familiar with the response, knowing that most substance abusers are ashamed or frightened — deterred by the stigma attached to drug use and terrified they might not get their next dose soon enough to endure withdrawal.

In most places, the drama would end here. But in Bennington a new collaborative program is being tested, targeting alcohol and substance abusers who have fallen through the cracks. The pilot program partners the Bennington Rescue Squad with the peer recovery organization Turning Point Center of Bennington (TPCB) in what the Vermont Office of Emergency Medical Services calls the first collaboration of its kind in the state. Organizers hope it will offer a blueprint for other rural communities as well.

Bennington lies in the southwestern corner of Vermont, one of the most rural states in the nation based on the size of its towns and cities. It’s the biggest of 17 towns in Bennington County, an area of 678 square miles with a total population of 37,183. The rural character of the county, with its population spread over a wide swath of mountainous terrain, creates challenges for EMTs, who serve a much larger area than their urban counterparts.

But Bennington’s smaller scale as a city of about 15,000 has also helped align nonprofit organizations, rescue workers, and the police in their efforts to combat the town’s snowballing drug and alcohol crisis.

Bill Camarda has been executive director of the Rescue Squad for a year, capping a 27-year career in Emergency Medical Services (EMS) in New Jersey and Vermont.

“Because we do have that small town, close-knit community, it makes collaboration easier than in an urban environment,” Camarda said. “I think about my experience in New Jersey and know partnering there would have been difficult. Certainly it would have been harder to identify the right person or group to work with.”

In recent years, Camarda has seen his crew of 28 respond again and again to overdose cases, pumping a patient full of Narcan, only to find they’ve overdosed a second, even a third time, weeks, sometimes days, later.

Weighed down by negative news?

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.“The program [with TPCB] came about because we’re seeing a lot of overdose or substance abuse related cases and it felt kind of like insanity. We kept doing the same things over and over again with the same failed result,” said Camarda, noting that unlike other emergencies, the team’s response often felt like they were just delaying death.

But since September, the Rescue Squad’s partnership with Turning Point has offered these individuals a chance at recovery. For Margae Diamond, TPCB’s executive director, collaboration with the EMS allows her organization to identify people in need of help with precision, rather than a scattershot approach that can at best only target at-risk communities.

In practice the tag-team approach means that when Rescue Squad EMTs encounter what they think could be an addiction case, they include details in their daily log that could help the squad director make a determination. His referral list is then emailed securely to Turning Point — a weekly average of 10 potential clients to visit within 72 hours after the referral.

Signs like liquor bottles or hypodermic needles scattered in the house, track marks on a patient’s arm, a fall that is clearly linked to alcohol abuse and, importantly, the number of times the squad has visited the same patient, are telling evidence, Camarda explained.

Patient confidentiality was initially a stumbling block. But following protocol already established with the local hospital, Turning Point coaches have been granted access to certain information by joining the EMS as volunteers in a non-clinical role, according to Camarda.

“We’re targeting a very specific list of people that refuse transport to the hospital after having been seen by the Rescue Squad for a substance use disorder. That means literally reaching out to an identified individual, instead of forcing them to find us to get help, which can seem insurmountable to them,” said Diamond.

Both Camarda and Diamond are quick to note a big part of that weekly list is related to alcohol abuse.

“Alcohol is the biggest substance abused in our community, especially with older adults,” said Camarda. “About two-thirds of the cases we encounter or refer are related to alcohol and about two-thirds of all substance abuse disorder are older adults over the age of 49 or higher.”

“Slowly forging a relationship”

The aluminum storm door opens a crack, just enough for Dylan Johnson, Turning Point’s outreach coordinator, to be heard. He runs through the broad strokes of TPCB’s partnership with the EMS, explaining he’s following up on last night’s emergency call.

Plainspoken with a gentle manner, Dylan hands the householder a black nylon harm- reduction bag containing two doses of Narcan nasal spray and several fentanyl and xylazine drug-testing strips. The man, unshaven in a worn T-shirt, is wary but willing to listen. The outreach call ends in rejection — “Not interested, thanks”— but as Dylan says, each return visit builds on the first, slowly forging a relationship.

“So much of this is trust. We don’t ever dictate, especially with a new client,” said Dylan. He understands the push and pull addicts can feel about recovery. They long to sober up, but the physical and psychological lure of drugs and alcohol traps them in a terrifying cycle. A former heroin addict himself, with five years of sobriety under his belt, Dylan knows from experience that it often takes a long time for an addict to summon the courage to walk into the refurbished mill that houses Turning Point’s offices.

“There was a time when I lied and cheated and stole from people who loved me,” he said. “How can I judge these people? But putting ourselves out there, meeting them, treating them like human beings means that when they are in crisis or ready to face their addiction, they will come to us.”

Rescue Squad Director Camarda put it differently:

“I sometimes feel disappointed that [our success rate] is only one out of seven [who seek help], but when I bring that number up to [professionals in the recovery field], they see it as huge, and it is huge when you consider we’re talking about hundreds of encounters, which translates into dozens of referrals that otherwise would never be entering peer recovery or treatment options.”

At another time in her life TPCB’s Diamond worked as a vice president for the financial service company Charles Schwab. Patience is not in her DNA. But working at the center has taught her that progress in the recovery business is about playing the long game.

“Our mission is about helping people find their own path to recovery, whatever that looks like, and supporting them through it,” she said. “We never give up. Period.”

In Bennington, people who deal directly with drug and alcohol abuse are increasingly convinced that, in the long term, working in tandem as a community on the myriad of problems, from housing to domestic violence, that underpin addiction is the only way forward.

Turning Point and the Bennington Rescue Squad see their partnership as the beginning of that bigger, more collaborative approach to addressing the drug and alcohol abuse.

As Diamond puts it: “Substance use disorder is the driver of a lot of the harm in this community … we need to come together, all of us, to solve the problem.”