When Randolph County’s $242 million Riverstart Solar Park is completed in 2022, it will be Indiana’s biggest. Thousands of photovoltaic panels covering 1,400 acres of rural land will generate enough clean electricity to power 36,000 homes.

Massive solar farms like this can be a touchy subject with locals. So, in the lead-up to the project’s approval, county legislators ensured the developer would be a good neighbor, with measures to avoid glare from the panels and mandated setbacks from roads and highways. And then they took it one step further, requiring the planting of pollinator-friendly plants like wildflowers and clover, in addition to native grasses. It was the first such mandate in state history.

The requirement will ensure that Riverstart will benefit the very land it is situated on — a very different approach from the way solar farms have historically been conceived and built. Typically, U.S. solar projects are built on marginal lands or farmland, with panels mounted on ground covered with gravel or turf. It’s a farm in name only, an ecological dead zone, despite the clean energy benefits. But as the ordinance for Riverstart shows, this is changing, and solar farms are increasingly being seen as more than just a means to generate clean energy.

Riverstart’s design takes into account the health of bee populations, which is critical because we rely on pollinators to fertilize our food plants — everything from apples to almonds, blueberries to squash. Bees are in decline in many parts of the world. Fruit trees on some Chinese farms are now pollinated by feather-wielding humans, and just last year, the U.S. Department of Agriculture funded a grant exploring the use of drones to pollinate fruit crops in Washington State. For Randolph County, about 80 miles northeast of Indianapolis, the ordinance approval comes at a time when Indiana’s native pollinator species have declined below the number needed to pollinate crops, with honey bee colonies in some areas facing collapse.

“It will help the bees, which are under attack,” said Michael Wickersham, one of the three Randolph County commissioners who approved the zoning ordinance and notes that the required vegetation will be low maintenance (no mowing) and aesthetically pleasing. “Adding the pollinator [plants] back into the ground is nothing but a win-win.”

It’s not just megaprojects like Riverstart that are embracing new solar farm designs that benefit the local environment. Dave Gahl, Senior Director of Northeast State Affairs for the Solar Energy Industries Association, the national trade association for the U.S. solar industry, says growing native plants and pollinators on solar farms is a nationwide trend for “community solar projects” — smaller solar arrays (less than five megawatts) typically built on leased farmland. By comparison, a big commercial project like Riverstart will be designed to generate up to 200 megawatts.

Weighed down by negative news?

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.The very act of taking plots of farmland out of production for the typical 20 to 30 year lifespan of a solar project rejuvenates top soil degraded by annual cropping and chemical applications. This speaks to the reality that solar farms are often temporary, which only bolsters the notion that they should maintain the health of the land they’re situated on.

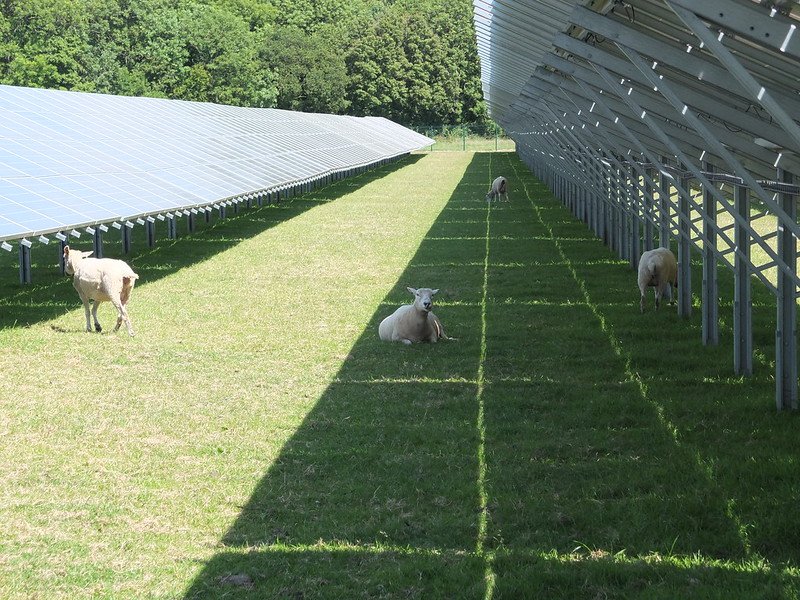

Solar farms with plants can also become fodder for “solar grazers,” like at the Nexamp community solar project in Newfield, New York, where about 150 sheep are “deployed” to prevent plants from growing tall and interfering with the solar panels. Fencing keeps predators out, while the panels themselves shelter the sheep from sun and storms.

Gahl says solar companies will sometimes enter into agreements with local farmers to allow sheep herds to graze the vegetation around the solar panels, providing another income stream for the farmer who is leasing the land to the solar farm. Such natural grazing also encourages grass regrowth, increases manure nutrients to the soil, and avoids the costs and pollution of mowing.

Meanwhile, new approaches are promising to expand the species of plants that can be grown at solar sites. The U.S. Department of Energy is experimenting with “agrivoltaics” — for example, raising solar panels higher off the ground to enable food crops to be grown in the shade underneath. In the summer heat of a place like Arizona, peppers and tomatoes can be shaded from the scorching sun by the panels, which then retain heat and boost the crops’ growth during the cooler evenings.

This co-existence of solar farming and food farming could just be getting started as solar farms become more sophisticated. Some newer solar panels can move, following the sun across the sky, generating up to 20 percent more electricity than conventional designs. To enable the panels to move, however, more space is needed between them, which opens up space for food crops to absorb sunlight alongside the solar panels.

Moving forward, solar farms could play a role in food security, as well. With big utility-scale solar farms alone predicted to cover almost two million acres of land in the U.S. by 2030, a huge opportunity is on the horizon to support pollinators, improve soil health, nurture biodiversity, produce food and, not least, slash emissions, all at the same time.