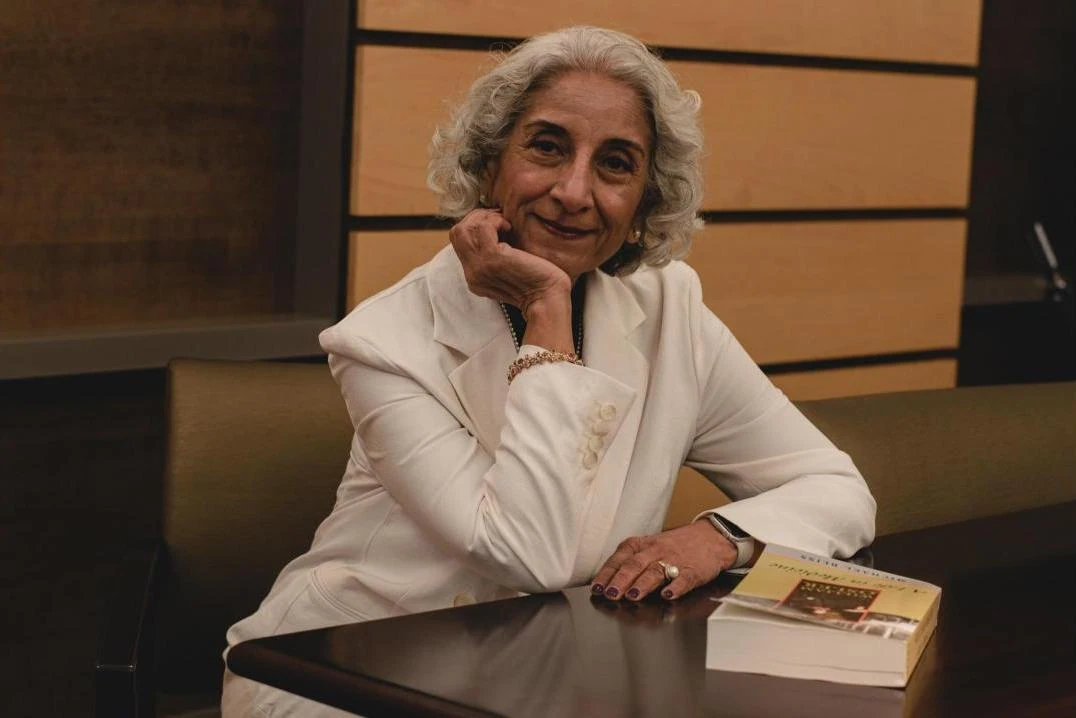

Last year, Geetha Jayaram flew back to the South Indian region of Karnataka near Bangalore, where she grew up. She visited her very first patient there, Eashwaramma. Twenty-five years ago, when the psychiatrist and the villager first met, Eashwaramma had not left her home in two years.

“I realized she was in the midst of a severe depressive episode that was complicated by panic disorder and agoraphobia,” Jayaram remembers the first encounter. “Her fear of leaving the house was so great that she did not even attend her own daughter’s wedding and could not help her husband in the fields. Everybody was very worried about her. They said prayers, brought home the priest and some thought she was possessed by the devil. I remember this first meeting so well because she said the devil was sitting on her chest.”

Jayaram did what she had learned as a psychiatrist at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore: She began by giving the woman medication and explained her diagnosis to her and her family. But the questions kept nagging at Jayaram: “Why had she suffered unnecessarily for years? Why had most of the people I treated over the past decades suffered unnecessarily for years? There is no health without mental health.”

Mental health care remains scarce in India, especially in rural regions, and the needs are enormous. Over 197 million people in a population of 1.3 billion have mental disorders, most commonly depression and anxiety. The suicide rate was at an all-time high in 2021 when 164,000 people died by suicide, or 120 suicide deaths per million people. India would need to add at least 100,000 psychiatrists to provide adequate mental health care, according to the Indian Journal of Psychiatry. “There is fewer than one psychiatrist for every 100,000 people,” Jayaram explains.

She knew she wanted to focus on women to make a difference: “Women suffer from depression and anxiety twofold or threefold the rate of men globally. Yet women are the key stakeholders in any community, the primary caregivers and drivers of any health care in the villages, so we targeted women first. When we treat women, we essentially take care of the entire family.”

India remains a country of contradictions. From a tech hub like Bangalore, you only need to drive less than half an hour to find yourself amid rural villages with unpaved dirt roads and straw-covered huts without running water. Jayaram estimates that one in three women in the region have been abused. Though the situation is slowly changing, women are still routinely married off as young girls “and treated like cattle, the possession of their husbands,” Jayaram says. “My heart goes out to the women because they suffer a great deal, including from domestic violence.”

Jayaram had first studied medicine at a local clinic, the Saint John’s Academy of Health Sciences, and in 2000, she suggested that the staff there incorporate mental health care. “You have to understand this is a rural area where you can’t even call an ambulance,” Jayaram says, “let alone a mental health specialist. So I felt a sense of urgency. I can tell you a thousand stories of women who urgently needed our help. I was raised to ask myself, What can you do about it?”

She decided to tie in her experience at Johns Hopkins, her concern for poor women and her expertise in community psychiatry in 2002 to initiate Project Maanasi, a collaborative care program interlaced with primary care. Maanasi means “of sound mind.“ This term was coined by the villagers of Mugalur, a core village about 30 kilometers outside Bangalore. Maintaining her full-time job as a Johns Hopkins professor in Baltimore, she started the program in Mugalur in her spare time while also incorporating research and teaching medical students, residents and nurses at Saint John’s. “We started with a door-to-door epidemiological survey of 17,000 households to assess the mental health needs. Depression and substance abuse were the most common, as is the case the world over,” Jayaram found. A crucial part of the solution was to integrate psychiatric care into the existing primary care clinic at Saint John’s. “Patients can get their health care and vaccinations there,” she says, “which helps decrease obstacles to treatment and reduce the stigma surrounding psychiatric help.”

Jayaram identified four women with a high school education who live in the villages and speak the local languages, and the project trained them to identify signs and symptoms of mental illness. Jayaram sees these women as the “backbone” of the program. “These dedicated health workers play the role of educator, role model and counselor,” she explains. “Supervised by the physicians at Saint John’s, they follow up with patients who are skeptical of treatment. Most importantly, they are there to listen and simply be a friend. Because they are accepted in the villages and understand our purpose, they hear of people who need help and are able to assess their needs.”

Focusing on women yields great results, which has also been recognized by the nationwide ASHA program (Accredited Social Health Activist). ASHA employs women across the country, initially to help cut infant and maternal mortality rates, but increasingly to incorporate mental health care.

The Maanasi project now serves a population of over two million households in 212 surrounding villages and offers medications at low or no cost to patients. “All this work has been made possible with Rotary grants and done with local Rotarians, primarily from the Bangalore Midtown Rotary club,” says Jayaram, who is a lifelong Rotarian and co-founded the Rotary Action Group on Mental Health Initiatives, which is now present in over 40 countries across the globe.

Weighed down by negative news?

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.The caseworkers might also go to see patients in their homes if people are unable to travel or bring them to the clinic if needed. “They trust our judgment, they come to us even for minor ailments like ear or eye pain, and we take care of them,” Gowramma, one of the health care workers says in a short documentary about the program. “They call us ‘the people who cure our headaches.’ They treat us with love and respect.”

For instance, Radha, a Mugalur resident, was married in her teens to a stranger. After her first child, she suffered from severe postpartum depression, and her husband disappeared with the infant. With outreach by the village caseworkers and clinical care, Radha recovered. Today she works to support herself, and her community supports her with the help and education of the integrated care workers.

Another woman, a 26-year-old flower seller, burned herself badly during a psychotic episode. “The caseworkers and villagers know to look out for her, make sure she has food and takes her meds,” Jayaram says. The villagers become an informal network and help each other out.

Another factor that distinguishes the Maanasi program is the wraparound care. “Community psychiatry means not just treating a disorder, but making sure the person is performing at his or her best,” Jayaram explains. “We treat all aspects of a patient’s life.” For instance, one woman wanted to become a seamstress after her mental health improved. Maanasi helped pay for her tailoring school and then Jayaram called around to find some donated sewing machines. The former patient is now running her own sewing school, often taking in other former patients.

Crucially, the caseworkers ensure “a continuum of care,” as Jayaram puts it, making sure the connections remain stable long-term. Sometimes patients get better and abruptly decide to stop taking their meds, as happened with Eashwaramma. After she improved with the initial treatment, she felt she did not need medication anymore and relapsed. The caseworkers recognized the need for ongoing medication before Eashwaramma was finally able to wane herself off for good.

With the help of her husband, Jay Kumar, an engineer, Jayaram got four scooters for the caseworkers, which enable them to visit more people. She is particularly proud that the caseworkers are computer literate and carry tablets where they can enter information at the bedside into a cloud-based database. Standardized research instruments are used to diagnose and document changes. “High tech, low cost,” Jayaram sums up the program. “This model is a forerunner in other parts of the world, including the US.”

When she started her medical career, Jayaram initially practiced internal medicine, but during her residency at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore, she became interested in understanding the interface between medicine and psychiatry. “To my eyes, psychiatry transforms the whole person for the better.”

When Jayaram first became chief resident in her department at Johns Hopkins, she was the only woman, the only person of color, and the only immigrant. “I was often in a room full of white guys,” she remembers. “I was paid 12 cents to [the] dollar less than the men.” She chose to train further in community psychiatry, which focuses on the severely mentally ill and those affected negatively by so-called “social determinants of care”—such as poverty, illiteracy, lack of transportation, and poor access to medical treatment. During her first eighteen years, she treated the inner-city poor of Baltimore: inpatient, outpatient, the emergency room, and volunteered outreach into patients’ homes.

This experience forged a vision to provide comprehensive and affordable care for the indigent in any setting. The World Health Organization targets mental illness and substance abuse as a critical component to Sustainable Development Goal 3: Good Health and Wellbeing. “I have treated both princes and paupers. Their sense of shame about mental illness is nevertheless identical,” Jayaram says. “We need to discuss mental health on the same platform as physical health. Through my work for over three decades in four continents, I can confidently tell you that we can successfully raise both awareness and knowledge, through outreach and repeated education, and we can provide access to early intervention, prevent relapse, and prolong wellbeing and gainful employment.“

Mental illness, Jayaram insists, is “both recognizable and treatable.”

“Without treatment, it robs us of who we are,” she says. “Our patients without care become mere shadows of themselves, mutely suffering. Had their families and communities been educated, and their neighbors taught, had they felt safe and comfortable talking about their feelings, emotions, and wellbeing, and had accessible services existed, they would have obtained help sooner.”

The Maanasi model has helped more than 2000 patients and has been copied in Kenya, Guatemala, parts of Canada, and in Lithuania.

In Kenya, Jayaram established an integrated care clinic that’s been taken over by the Ministry of Health and serves a population of half a million people. In Guatemala, she is setting up a similar care center for young girls who suffered from child marriages, domestic violence, rape, and illiteracy.

In Lithuania, people were seriously concerned about the alarming rate of youth suicide. With support from The Rotary Foundation through a global grant, Jayaram helped with a countrywide effort that involved numerous other partnering agencies and the Vilnius University School of Public Health to provide suicide hotlines and a workable system for treatment. This effort contributed to the significant decrease in suicide rates in 14 districts and saved thousands of lives in just two years.

When she visited Eashwaramma again, Jayaram was happy to see that her former patient is now staying with her son in a spacious two-story house, no longer depressed. “She has been weaned off medications for many years. She was vibrant, smiling, and welcomed us into their home, offering us tea and snacks,” Jayaram recounts. “Her recovery had come full circle, thanks to the Maanasi project. There are many women like her.”