Efraín López García was only 29 years old. On July 6 of this year, the hottest day so far recorded on earth, he complained about a headache and dizziness while harvesting fruit on a farm in Homestead, Florida, near Miami. His fellow workers told him to take a break, but when they checked on him a little later, they found him lying dead on his stomach.

He was one of many victims of the ever-intensifying heat waves that have gripped much of the US this summer. Garcia died in the midst of a stretch in which Miami-Dade County’s heat index — the measure of heat and humidity that tells you how hot it feels in the shade — had risen above 100 degrees Fahrenheit and the National Weather Service had issued a heat advisory every single day for several weeks.

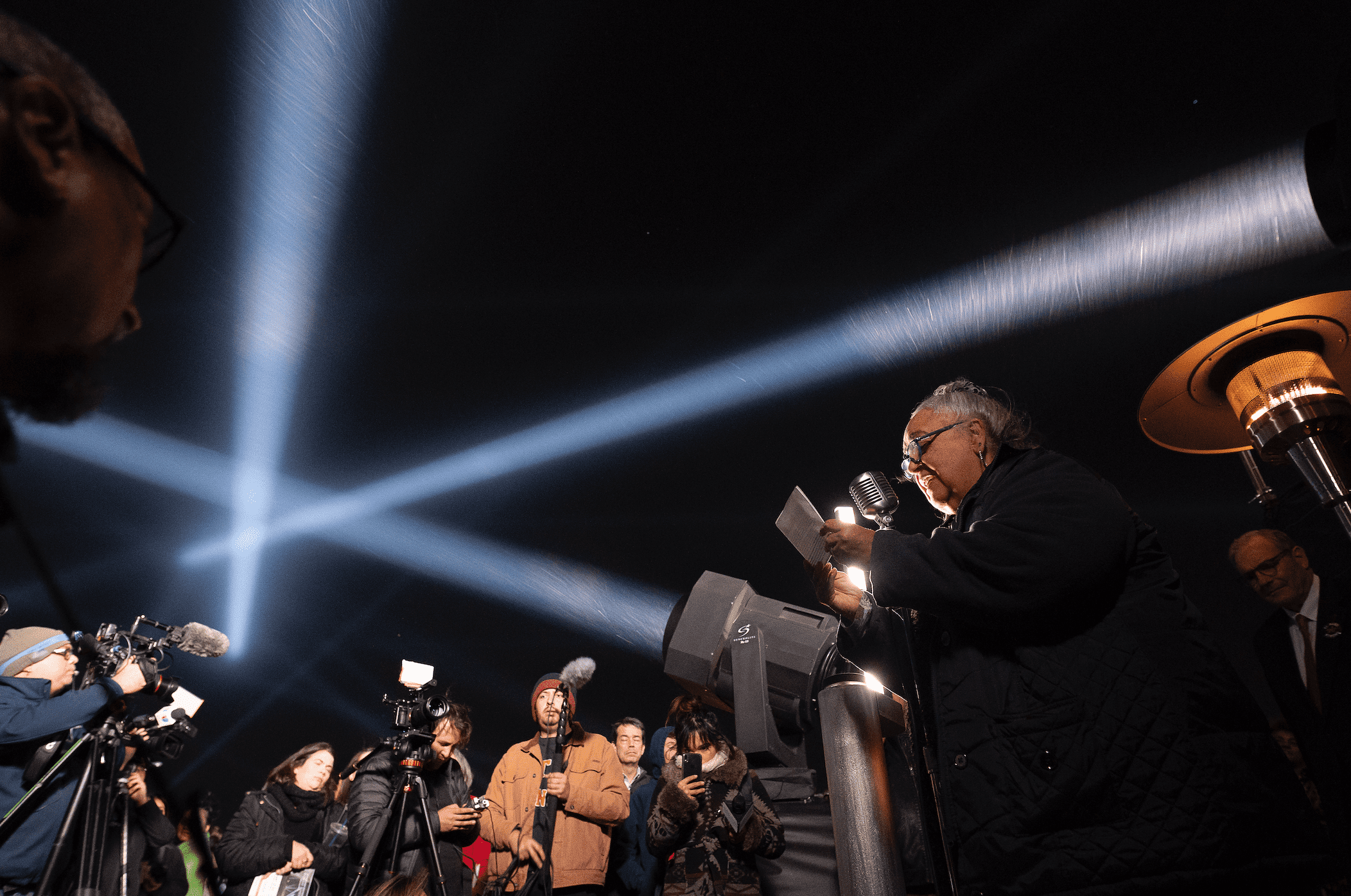

“Is that what we deserve? No. We’re human beings,” Alejandro Pérez, a member of the worker advocacy group WeCount, said at a press conference in Homestead in front of the county commission chamber a few days after Garcia’s death. “We deserve a dignified life and a decent job.”

Earlier this year, a 28-year-old Mexican worker was found lying in a drainage ditch in Parkland, Florida, killed by heatstroke. It was his first day on the job.

Roxana Chicas, a nurse and assistant professor at Emory University who did her PhD on heat-related illness in agricultural workers, is not surprised to hear of the workers’ relatively young age: Though old age can be a risk factor, heat stress often affects unsuspecting younger workers (because they push themselves harder) and those who just started working on a farm (because they haven’t acclimated yet). “Often, they get no training and no education on how to protect themselves,” Chicas says.

Agricultural workers are 35 times more likely to die of heat than other workers, followed by construction workers, who are 14 times more likely to die of heat stress than others. Their problems are exacerbated not only by climate change, but also by the fact that about 50 percent of agricultural workers are undocumented and have no health care. “It creates precarious working conditions because they don’t dare to speak up or insist on breaks,” Chicas says. “There’s also this common notion that heat stress is simply something that comes with the job, and that nothing much can be done about it.”

Though the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) recommends modifying work hours when temperatures rise and advises that employers should provide water, rest and shade, there are no federal protections and few state mandates in place. Employers in Florida, Texas and most other states have no obligation to protect workers from heat stress. On the contrary, Texas governor Greg Abbott recently signed a controversial bill that actually prohibits local municipalities from enacting heat protection standards for workers.

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.Like other experts, Chicas believes that heat-related deaths are likely significantly undercounted. When a worker’s heart stops due to a heatstroke, the cause of death is often noted as cardiac arrest, not heat stress. Moreover, the long-term effects and dangers of chronic heat stress in ag and construction are poorly understood because they have hardly been researched.

Chicas conducted the first-ever intervention studies in the field as part of her PhD, measuring workers’ core body temperatures with real-life biomonitoring equipment. Workers swallowed sensors to measure their core body temperatures throughout their workdays.

Together with the Farmworker Association of Florida, Chicas does participatory community research. This means that she gets up before sunrise to align with the workers’ schedules and listens to what the workers consider important. “We originally started out studying the effects of pesticides on the workers,” Chicas says. But so many workers complained about the heat that she changed course and now focuses on its poorly understood dangers.

Chicas is often the first person to educate workers about the symptoms of heat stress and how to respond in an emergency. “Nobody has trained them in first aid. I ask them, when your child has a fever, what do you do? You try to bring their temperature down by applying a cool towel to their forehead and give them plenty of fluids, right? Same here. Overheating essentially is like having a fever without the infection.”

The increase in climate-related risks is alarming. Heatstroke has become more frequent, but there is a much less obvious life-threatening consequence of working in humid heat: chronic and even fatal kidney injuries. A body temperature above 100.4 degrees Fahrenheit can damage organs, according to OSHA. When Chicas and Linda McCauley, her dean at Emory’s Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing, tested blood and urine samples of nearly 200 farmworkers, they found 33 percent had kidney injuries.

“Workers who are paid by the piece, by the quantity they pick versus by the hour, are more at risk,“ Chicas notes. “The piece-rate workers work at a much higher intensity because they want to pick as much as they can to make a little bit more money.“

Chicas and McCauley just finished a longitudinal study in Florida, analyzing 120 workers’ kidney functions over two and a half years. While they found that 10 percent of hourly farmworkers had damaged kidneys, by the end of the 32-month study period, 43 percent of the piece-rate workers had developed acute kidney injuries, and the injuries increased with the temperatures.

“People often are unaware that their kidneys are failing,” Chicas says. “Unlike with heatstroke symptoms, there are often no warning signs.” Chicas and her team were so alarmed by the findings that they went back to double-check the data to confirm it was accurate.

“The industry has portrayed the piece-rate system as a good system for the workers, because you have total control over when you start and end working and how many breaks you take,” Chicas explains, “but in reality, the pay is so low that it incentivizes and pushes workers to work much harder and forego rest breaks.”

For instance, workers are paid about 50 cents for every 32 pounds of tomatoes they harvest, a rate that has hardly changed in decades. As a result, a worker must pick more than two tons of tomatoes to earn minimum wage in a 10-hour workday, nearly twice the harvest of workers paid by the hour.

The industry has protested attempts to introduce heat protection for workers, claiming high costs. “Studies show that workers who take adequate breaks and hydrate are more productive than those who simply keep working without taking breaks,” Chicas has found. “These are facts employers need to hear, too.” And of course, no profit margin is worth a person’s life.

As part of the research project at the Farmworker Association of Florida, Chicas teaches farmworkers to listen to the first alarm signals of dehydration and heat strain in their bodies. She advises them to take breaks in the shade before their bodies overheat beyond repair, and the Association refers workers to field clinics for treatment. “It is kind of a safeguard to teach them when they feel these symptoms like headache, excessive sweating or heart palpitations, it’s okay to take a break,” Chicas says. “That kind of culture is not in place in the industry.”

Chicas’ motivation is personal: She was born in El Salvador, and her mother grew her own corn, coffee and beans, like many people in El Salvador. Kidney failure from heat is a leading cause of death for farmworkers in El Salvador and other hot climates. When Chicas immigrated to Atlanta, Georgia, with her mother at age four to flee the violence, she was undocumented. (She became a US citizen when she turned 18.) “I share that background with agricultural workers,” Chicas says. When the bilingual Latina was offered the opportunity to study, she chose nursing, motivated by the desire “to give back to the community, and help improve their working conditions, better their quality of life.”

For decades, in El Salvador and other parts of Central America as well as in Asia and Africa, large numbers of farmworkers suffered from kidney failure, including young people who didn’t have traditional risk factors like diabetes or hypertension. The cause was considered a mystery until doctors realized that the disease mostly affects farmworkers in hot areas and is likely a consequence of heat stress.

Unfortunately, drinking plenty of water is not always sufficient to stave off kidney damage under these conditions. Preliminary studies indicate that electrolytes could help. “When workers drank five liters of water per day, 23 percent still sustained kidney injury,” Chicas says. “But in the group of workers who drank five liters with electrolytes, none had kidney damage.”

In the absence of legal protections, Chicas is educating workers about additional measures they can take — for instance, wearing cooling bandannas or cooling vests to lower their body temperature and taking breaks in the shade before their body temperature spins out of control. “It should be an expectation for workers to take breaks when it’s really hot,” Chicas says. The Farmworkers’ Association of Florida, too, is advocating for heat protection standards and urges employers to provide clean water, shade and breaks.

However, Chicas finds that the mantra Water-Shade-Breaks is not enough. Even in states such as California and Oregon, where minimum protections are in place, kidney disease continues to be a silent killer. “We need more robust policies and interventions to protect workers,” she says. “Some industries are required to hand out protective gear to workers. Why not have employers provide cooling devices?”

In mid-August, she will start testing a new biopatch on construction workers. The sensor on the patch that workers wear on their chest can send alerts when the core body temperature rises critically or when other alarming signals indicate heat stress. Workers’ smartphones could also be equipped with apps that alert workers about stress signals.

However, Chicas cautions, “There is really nothing that substitutes [for] mandatory worker protections.”

A week after Greg Abbott signed the Texas bill into law, 24-year-old Gabriel Infante died of heatstroke on his first work day at a construction site in San Antonio, Texas, digging to move internet fiber cable under the hot sun while temperatures exceeded 100 degrees Fahrenheit. When Infante complained about dizziness, his co-worker Joshua Espinoza poured cold water over him to cool him down. According to Espinoza, a foreman insisted he call the police and pushed for a drug test instead of recognizing the acute heatstroke symptoms.

By the time Infante reached the hospital, his internal temperature was a fatal 109.8 degrees.

Chicas hopes the relentless heat waves create more awareness not just among workers but also the general public about “how heat affects us, and that we have the responsibility to push for policy change before it’s too late.”